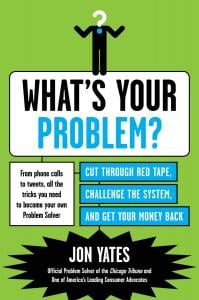

The Chicago Tribune "Problem Solver" Jon Yates joins us on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm with consumer tips in his new book: What's Your Problem? Read an excerpt from the book below.

Introduction

The Power Within

Romy Kaminski knew how the system worked. She had spent six years as a benefits coordinator for an insurance broker, helping fellow employees navigate the labyrinthine health care system. She knew the games health insurance companies play, she knew how to speak their language, and she knew how to get results.

Or so she thought.

When she got laid off, Kaminski couldn’t afford the $1,300-per-month COBRA payments required to continue with her former employer’s health insurance plan. Instead, she signed up for a $225-per-month, no-frills, catastrophe-only plan with a company called Assurant Health.

As luck would have it, catastrophe soon followed. A month after signing up with Assurant, Kaminski collapsed in pain and was rushed to the hospital. An undetected brain aneurysm had burst.

“The guy on the CAT scan machine actually said, ‘Oh my God,’ ” Kaminski remembered. “He said, ‘You have tons of bleeding on your brain. I can’t believe you’re actually talking to me.’ ”

Doctors performed two surgeries on her brain, and she spent almost two weeks in intensive care. She could never have imagined that her time at the hospital would be the easy part, but by the time she returned from the hospital, her medical bills had beaten her home. She got out her calculator and pecked away frantically, trying to keep up. It made her head hurt all over again.

One bill was for a mind-boggling $162,000. Another was for $84,000, and a third came in at $20,000. Assurant refused to pay any of them. The insurance company ordered all of her medical files, then scoured them to see if she had a preexisting condition—anything that would allow it to deny payment on her claims.

“I absolutely know what’s going on behind the scenes,” Kaminski said at the time. “They don’t want to pay the bill. They’re stalling, stalling, stalling. Delay and don’t pay; that’s their tactic.” The former benefits coordinator tried everything she could to convince the company to pony up. It wouldn’t budge.

More than six months after her first surgery, Kaminski owed the hospital more than $310,000. Tired of waiting for Assurant to pay, the hospital began sending Kaminski threatening letters, demanding its money immediately. If Assurant didn’t come through, she’d be forced to file for medical bankruptcy. Her credit would be ruined. Her savings would be wiped out. Out of utter desperation, Kaminski wrote to me for help. Less than a week after I called Assurant, the insurance company agreed to pay almost everything.

That’s what I do. I’m the Problem Solver.

My job is to cajole, threaten, or bully businesses and bureaucracies into doing the right thing. I write a column for the Chicago Tribune in which I stick up for society’s Davids in their everyday battles against the Goliaths. I am a journalistic enforcer, a heavy, the newspaper’s consumer conscience.

With a mere phone call, I can correct erroneous cable bills, convince the city to throw out bogus parking tickets—or help a wayward insurance company see the light. I can get an airline to pay for lost luggage, and ensure the gas company doesn’t turn off a poor customer’s heat in the middle of winter.

Why am I telling you all of this? It’s simple: if I can do this, so can you.

Trust me, I am not your stereotypical thug. Growing up, I was the kid who mouthed the words in chorus, only pretending to sing because I was sure my classmates would laugh at my off-key warbling. I was the second grader who, when my family moved across town, secured a waiver from the school district so I could continue attending my old elementary school. The thought of making new friends petrified me. In college, professors routinely docked me full letter grades for not speaking up in class. I wrote an essay about my shyness for freshman rhetoric class. My professor thought it was a cry for help and asked me to read it in class. I refused.

When I left my home state of Iowa to become a reporter at a newspaper in Palm Springs, I spent my first night in the California desert holed up in a hotel room, sobbing with fear. I kid you not.

Years of solving other people’s problems have made me a pro at it, but I’m no tough guy. At 5 feet 7 inches tall, I do not cut an imposing figure or speak with a booming voice. I will never be mistaken for a professional hockey enforcer. I still waver when faced with confrontation and I still dread arguments, even when I know I am right. At dinner parties, I prefer to fade into the background and let my hypersociable wife, Trine, speak for both of us.

My point is not that I am a wimp, although I’d understand if you drew that conclusion. My point is that if I can convince seemingly uncaring bureaucrats and businesspeople to do the right thing, so can you.

Don’t get me wrong, I do not believe all corporations are evil, or that all customer service agents are sadistic turds. I do not hold a grudge against government employees, or think they secretly revel in making our lives miserable. Most public servants are fine, upstanding people, and most corporate employees are caring and nice.

But this book is not about them.

This book is about their wicked co-workers who listen but do not hear, make promises they do not keep, and who strive to torment us with each pinprick of lousy customer service.

In my years as the newspaper’s Problem Solver, I have learned a few things about the business world. It’s true that a large part of my success is thanks to my column. As they say, “never pick a fight with a man who buys ink by the barrel.” Businesses and elected officials will almost always correct a mistake at the mere threat of negative publicity.

But my success cannot solely be attributed to my journalistic muscle. Over time, I’ve discovered that the key to solving your own problems comes down to three basic and universal understandings.

First, all companies, corporations, and utilities are in business for one reason: to make money. To convince them to repair your faulty television or your out-of-whack electric bill, you must first convince them that not fixing your problem will cost them more in the long run. When it comes to big business you have to speak its language, and that language is money.

Second, most bureaucrats, bigwigs, and fat cats hate confrontation almost as much as we do. If you push them far enough, they’ll cave.

Third, courtesy only gets you so far. Before I realized how the system works, I believed another old adage: “you can catch more flies with honey than you can with vinegar.” And sure, if we all treated each other with courtesy and caring, honey would work every time. I always encourage readers to play nice when initially attempting to resolve their problems. Lord knows, we could use a little more civility in this world, and if we can solve a problem with a smile, all the better. But in many cases, the system is designed to chew up and spit out the honey. It only responds to the vinegar, so it’s often necessary to store some anger in reserve.

Excerpt from “What’s Your Problem? Cut Through the Red Tape, Challenge the System, and Get Your Money Back,” compliments of William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers

For more on Jon Yates and his book, visit the links below.