It’s a how-to guide to the best bars and scandalous shows in the Second City. But don’t try to find the saloons or “free and easy shows” it recommends--most have been closed for over a century.

Chicago By Day and Night: The Pleasure Seeker’s Guide to the Paris of America hit the newsstands in 1892, aimed at the millions of tourist who would flood the city one year later for the Columbian Exposition. Inside is advice on everything from hotels and gambling houses to “a complete refutation of the libelous assertion that Chicago is the wickedest city in the world.”

Chicago By Day and Night: The Pleasure Seeker’s Guide to the Paris of America hit the newsstands in 1892, aimed at the millions of tourist who would flood the city one year later for the Columbian Exposition. Inside is advice on everything from hotels and gambling houses to “a complete refutation of the libelous assertion that Chicago is the wickedest city in the world.”

The guide is getting revived by Chicago historians Paul Durica and Bill Savage, who have edited and annotated a new edition. Durica is founder of Pocket Guide to Hell Tours and Reenactments, and Savage is a lecturer at Northwestern University. They join us on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm.

Chicago By Day and Night was written for “the sophisticated gentleman and the country rube,” Durica says. “But it’s also tricking the country rube into thinking of himself as a sophisticated gentleman.”

That’s because even visiting Chicago in the 1890s was seen as extremely novel. “There had never been a city like Chicago in the world, in terms of its scale and the speed in which it achieved its scale,” Durica says. “It would have been intimidating for anyone coming from outside a New York or Paris.”

The book details some of the seedier places in the city to gamble or drink--but not before admonishing the reader to stay away. Take this line from a section on gambling:

The book details some of the seedier places in the city to gamble or drink--but not before admonishing the reader to stay away. Take this line from a section on gambling:

“The compiler of this little work advises everybody to forego all games of chance while resident in this city. Confident, however, that with many people old enough and wise enough to know better this advice will utterly be disregarded, a few remarks upon the present status of the gambling fraternity may not be thrown away.”

“It’s a very standard, late 19th century tactic,” Durica says. “‘We’ll talk about gambling or saloon culture in this very negative way, but still give you all the info you would need to pursue the activities. It’s a wink-wink, nudge-nudge...There’s a great line in the book, ‘Of course no well regulated person ever enters a saloon except for purposes of investigation.’ But never to actually have a drink.”

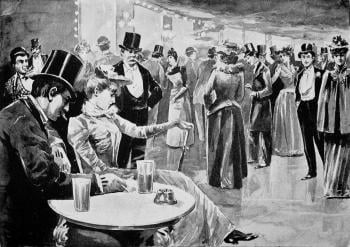

Frequent references to theaters, restaurants, and parks where men and women could publicly mix may strike a modern reader as belabored. But the Victorian cheat sheet would have been invaluable for contemporary travelers. “In the nineteenth century such mixing was seen as an inherent moral threat, and not without cause,” Durica and Savage write in their introduction. “Women who freely went to any public place, much less saloons, or performed in the theater or otherwise led public lives, were assumed to be sexually available, if not outright prostitutes.”

Women in public were so sexually threatening that special attention was paid in the guide on how to avoid the adventuress, or “shrewd” women who would con men after their illicit liaisons. One con was called the “panel game”: the adventuress, after some flirtation, would invite a man up to her bedroom, with nothing but a bed and a chair. While “in the middle of the act,” a panel in the wall would slide back and an accomplice would emerge to steal the man’s wallet from his coat on the chair.

Women in public were so sexually threatening that special attention was paid in the guide on how to avoid the adventuress, or “shrewd” women who would con men after their illicit liaisons. One con was called the “panel game”: the adventuress, after some flirtation, would invite a man up to her bedroom, with nothing but a bed and a chair. While “in the middle of the act,” a panel in the wall would slide back and an accomplice would emerge to steal the man’s wallet from his coat on the chair.

“Victorians have a reputation for being prudes,” Savage says, but brothels and erotic shows were a big part of Chicago nightlife. “The mixing of the sexes in public spaces was a big part of living in the big city. But much of our sexual life [then] was still based on rural life--such as never speaking to someone you didn’t know, which seems quaint, but was a means of protecting yourself from adventuresses.”

Chicago By Day and Night was printed in 1892, for the World’s Fair the following year. But before the White City is built, the country’s economy suffers a severe depression. One of the great ironies of the guide, Durica and Savage say, is that by the time tourists could use it, most of the hotels and restaurants inside had gone out of business.

“So much of this stuff about contemporary culture is consumed for such a brief period and then discarded. In 100 years, they’ll be binding The Chicago Reader or TimeOut,” Savage says. “[This reprint] is rescuing this ephemera from the past.”