Jeanne Nolan says her childhood was fairly typical for Winnetka in the 1980s: preppy clothes, early plans for college, and few serious things to worry about. But, in 1987, after becoming passionate about the environment, Nolan began to question what she saw as the harsh materialism of the suburbs.

Jeanne Nolan says her childhood was fairly typical for Winnetka in the 1980s: preppy clothes, early plans for college, and few serious things to worry about. But, in 1987, after becoming passionate about the environment, Nolan began to question what she saw as the harsh materialism of the suburbs.

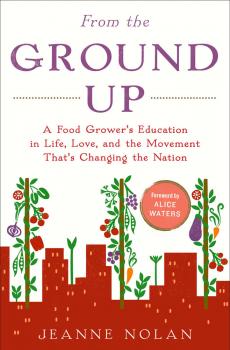

“I’d started to see things in terms of either/or: Either you lived in the materialistic world or lived an ascetic, spiritual life; either Winnetka was all good or it was all bad,” Nolan writes in her book, From the Ground Up: A Food Grower’s Education in Life, Love, and the Movement That’s Changing the Nation.

Nolan dropped out of high school and took a road trip across the country. When she came back to Winnetka, she was still looking for a way to remove herself from modern society. That’s when her mother saw an ad in the Chicago Reader for Zendik Farm, a commune outside San Diego that practiced organic farming.

The farm taught Nolan how to raise fruits and vegetables in arid climates, without using pesticides or artificial fertilizers. But over nearly two decades, Nolan came to realize the commune embodied many of the aspects of a dangerous cult. Anything outside the farm was considered a “death culture,” and strict rules pushed members to cut ties with their friends and families.

"We were almost never alone when talking to friends and family, and we felt constantly monitored: Any excess of warmth we showed to an outsider was taken as proof that we valued the wider world too much and weren’t fully committed,” Nolan writes.

There were also rules about romantic relationships: while sex was encouraged among members, one wasn’t supposed to become attached romantically to anyone else for fear it would harm the group dynamic. And parents were similarly discouraged from becoming too close to their children, letting them instead be raised by the community.

Even though Nolan was pressured to renounce a serious romantic relationship and step back from her daughter’s upbringing, for a long time she still could not imagine leaving the farm.

“At the time, I couldn’t imagine any kind of life outside Zendik Farm,” she writes. “I basically equated leaving with committing suicide.”

But after 17 years, when her daughter was 2, Nolan says she “escaped” back to her parents in Winnetka. There, still in shock and without an immediate career, she used her farming skills to set up a vegetable garden in her parents’ backyard. At the urging of her friends, she formed a business, The Organic Gardener, and now creates and maintains organic gardens throughout the city and suburbs. She created the Lincoln Park Zoo’s Edible Garden and has worked with schools and nonprofits to teach Chicago students about the value of fresh food.

Nolan joins us on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm with more about her life on Zendik Farm and why she still feels so passionate about organic farming.

I read a few articles written about you and your business as recently as 2010, which don’t mention the specifics of your time on Zendik Farm, just that you found “an apprenticeship at a 75-acre farm with a 2-acre vegetable garden in Southern California.” How difficult was it, in the book, to spell out exactly how life on the commune was like?

I read a few articles written about you and your business as recently as 2010, which don’t mention the specifics of your time on Zendik Farm, just that you found “an apprenticeship at a 75-acre farm with a 2-acre vegetable garden in Southern California.” How difficult was it, in the book, to spell out exactly how life on the commune was like?

I would categorize it as difficult. I like to be honest when I can. I feel good being up front with people. But there have been times when I haven't been ready to. And I think with writing the book, I decided to be revealing about myself because my story had enough about it that could be related to, more universally. Some of the themes in my life, and things I’ve struggled for and with, others have too. And it all comes around to me caring deeply about the movement I’m involved with, seed to table, and wanting to spread that message further.

So did you tell any of your clients, or friends you’ve made since you came back to Chicago, about your experiences? Or did they also have a rosier impression of your time at Zendik?

For many of them, reading the book will be the first time they really know my story. The process of writing the book brought me face to face with aspects of my life that I myself had swept under the rug a bit. I wasn’t looking that closely day to day.

I hoped you could tell me more about a moment you say you’ve unconsciously spent your whole life trying to recapture--this is where you’re 10 and playing hide and seek.

The scene is set as I’m just a neighborhood kid playing and I stumble upon a vegetable garden that a neighbor is growing. Have you ever had one of those moments where time stops? It goes into slow motion. That’s how I recall the moment, almost as if I had extra senses that got turned on, being able to smell and feel soil, and the cushiony, loaminess of it beneath me. The feeling was I was covered in a green dome, I wasn’t seeing the houses beyond.

Eating the food that was growing right there, munching on a cucumber. It was a powerful moment for me, for sure, and it was powerful in its peacefulness. Part of the reason it was so powerful is it was juxtaposed against the rest of my life, which was a lovely life, your average suburban kid in the late ‘70s. I wasn’t in danger, but I don’t think I was experiencing a lot of bigness, or sense of connection to deeper parts of me.

You now call Zendik a cult, and say that you and others there were indoctrinated. Do you think the leaders of the farm were well-intentioned but poor leaders, selfish, malevolent, or something else entirely?

I would go for a combination of the three, for sure. I have moments when I think back on the leaders, who are both now deceased, and I have occasional moments of fondness and sadness that they’re gone. I have more moments of, “Why didn’t I stand up to them? Why did I let them do awful things to others, to me, and why didn’t I treat them like anyone else and say, ‘That doesn’t make sense. What was that power that they held?’

There was a lot that they did that they were very unconscious about. They felt inside themselves that they were good trying to do good. They didn’t set out consciously to do wrong to others. Was that because in some ways they were juveniles or unevolved, and really weren’t so well-intentioned? I think so. They were faulted, like all of us are, and not full-on psychopath, but they had some issues.

Do you regret moving to the farm?

In 17 years, I formed me there. I started my family there. [Nolan gave birth to her first daughter on Zendik Farm, and met her husband there]. I love my life and the people in it. So there is not regret about the overall journey. But there are still things that make me cringe, especially things that affected loved ones.

You left the Chicago suburbs in a rejection of a materialistic culture, and while you still eat organic and are environmentally conscious, do you ever feel uneasy about owning a car or shopping at a mall?

You left the Chicago suburbs in a rejection of a materialistic culture, and while you still eat organic and are environmentally conscious, do you ever feel uneasy about owning a car or shopping at a mall?

I probably struggle with wishing my life was greener mostly. I wish I could be driving in a non-polluting car. When I’m using my washer and dryer, and my dishwasher, I need to use them. The neighborhood I live in would not appreciate a clothesline. I don’t feel good about that. As I’ve matured, I’ve had to accept compromises. It’s kind of like with our business. We’re often putting gardens in lawns, and there’s a golf course next door that’s totally chemically treated. I’m still, in a certain way, reentering society.

Would you ever turn down a request for an organic garden if you felt the client didn’t share your ideal, or was apathetic towards them?

I love to help people grow food. I will do it almost with anyone, anywhere. We recently put a garden in at Old Orchard Shopping Mall, right across from Anthropologie. Right in the middle of the shopping hub, where everybody's being materialistic! But it’s a positive no matter where you do it.

I see it as an opportunity to broaden their lives. I think growing food is a very positive lifestyle change. It brings people back to the table, more in touch with the earth. If somebody was doing a garden mostly to show off to their friends, but weren’t very passionate about it, I’m OK with that. There’s good in there.

What are three of the most common mistakes you see people make when they’re trying to start an organic garden in their backyard?

Not preparing the soil, for sure. Not understanding the soil relationship to the success of growing food. I get a phone call, “I threw some carrot seeds in my flower bed and nothing happened.” You need to aerate to open up the existing soil. And then adding compost is a must. You need to bring in a nutrient-dense soil for the plants to grow in.

Another is overcrowding, planting too densely. It is very hard, even for well-seasoned gardeners, to use the restraint needed when planting. People won’t thin out their crops as they’re coming up. Also, some of your plants go into the ground as a plant, not a seed. When you’re putting them in, you should consult a gardening resource to help you determine how far apart they should be.

And a lot of people wait too long to harvest .There’s some separation anxiety--you grew this plant and it’s beautiful. You mean I need to cut off this head of broccoli? But if you wait too long, it will flower and you will have missed the window. And sometimes you have to try it. Taste that arugula, open up the pod of edamame beans.

Interview has been condensed and edited. Images courtesy Jeanne Nolan.