Alfonso and Margaret Iannelli were a husband and wife design team who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright and then struck out on their own. They made their mark on the Chicago area, from the Adler Planetarium to the Pickwick Theatre in Park Ridge.

We revisit a conversation with Chicago cultural historian Tim Samuelson on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm about this artistic power couple, and a show of their work at the Chicago Cultural Center called Modernism’s Messengers: The Art of Alfonso and Margaret Iannelli. The exhibit opened on May 18 and will run through August 18.

Watch a 2011 Chicago Tonight story about Alfonso Iannelli:

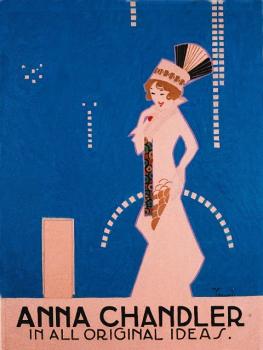

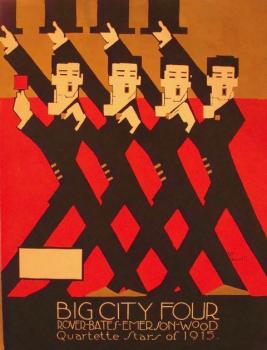

A new book by David Jameson about the artist was released in July. One chapter from the book titled Alfonso Iannelli: Modern By Design is about the posters he designed for the Orpheum Theater in Los Angeles in the early 1900s. View a slideshow and read the excerpt below:

The Orpheum Vaudeville Posters 1912 - 1915

Excerpt from Alfonso Iannelli: Modern By Design

by David JamesonORPHEUM POSTERS 1912 - 1915

------Iannelli couldn't have known at the time, at age 24, that his job designing the lobby window for Los Angeles' new Orpheum Theater would lead to his breakthrough into Modernism.

Kohn and Castle, the builders of the new theater, hired him in May of 1912 to design a three-part window over the doors to the lobby. They would have been pleased with the result, as Iannelli's window resembled the Maxfield Parrish illustrations then becoming famous. Soon after, the Orpheum management asked him to paint lobby "showcards" for the travel- ing vaudeville acts. After a year or two of his appropriately decorative posters, Iannelli's approach developed a far more modern graphic language—probably outshining some of those same acts.

Years later, his own reminiscences of the Orpheum years were to constitute a substantial portion of his unwritten autobiography:

"Following my quest of doing problems that were of immediate necessity to the people, I undertook to make the posters for the Orpheum Theatre, four or five a week, which were displayed in the Italian Renaissance lobby—five frames on each wall—five of the coming attractions and five of the running."

Rectangular cut-outs in each of the tempera and metallic ink paintings permitted the management to insert photographs of the performers or the changing dates of their appearances whenever the acts returned to the Orpheum.When the management offered Iannelli the opportunity to produce these lobby advertisements, he approached it as just another illustration job.

"These were showcards when I first saw them, but it seemed to me this was a wholly proper field for an artist to solve quickly and the legitimate avenue for the best work of any artist."

Coming from his illustration background in Cincinnati and New York, having worked for clients not used to pushing the accepted boundaries, his early posters were more in the vein of contemporary illustration than they were European avant-garde. In March of 1913 he painted Sarah Bernhardt, performing in Los Angeles in one of her numerous "farewell" tours, in soft pastels and fur. But even in this sea of froth, he framed her face with a frizz of flaming red hair.

"The early efforts at my analysis of the poster was the use of flat tones of tempera colors on tone backgrounds—lettering arranged as part of the design achieving a mood relevant to the subject."

The metal lobby frames displayed the posters as linked pairs of which Iannelli took full advantage. Some of his early tracing paper studies showed arrangements down the wall that geometrically linked each subject to the next, carrying over one background motif or line into the adjacent poster.

"At one point of the development, a metamorphosis took place wherein the applied forms of color were seen as a coordinated part of the total area and all of the spaces of color and background areas worked together so each played its part in the scheme, letter- ing included."

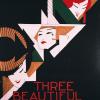

The difference between the October 1913 poster for Saharet and the poster for The Orpheum Beauties, done in 1914 is typical of Iannelli's profound change in style.

This metamorphosis coincided with his commission from the great architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, to sculpt the concrete finials on his new Chicago project, Midway Gardens. From then on, Iannelli's graphic arts became infused with a sense of architecture, geometry and simplicity.

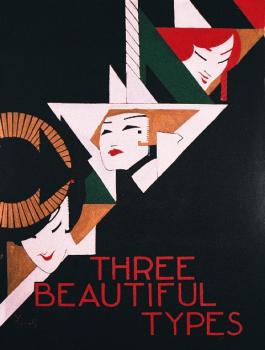

Iannelli credits The Orpheum Beauties as being the first of his vaudeville posters to express the "first successful con- trolled design...using the whole space and its subdivisions of FORM & COLOR VOLUMES as a complete organization."

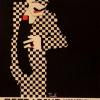

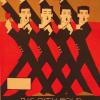

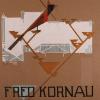

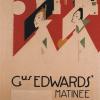

By August of 1914, Iannelli flooded the lobby with triangulated faces, crossword puzzle costumes and asymmetrical blocks of vivid, saturated colors. Fred Kornau, the Viennese whistler, was depicted that month as a scarlet slash of a bird perched on a geometric tree branch. By September, the hats he placed on Gus Edwards' Matinee Girls had become a collision of paralellograms. The more obscure the act, the more Iannelli would contort his images into a near psychedelic abstraction.

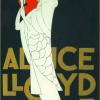

If art is, essentially, language, then Iannelli was creating a new dialect with geometry as its grammar. For the November poster for Meehan's Canines, he overlapped arcs of leaping hounds in orbit around a golden orb to promote a simple dog act. In March of 1915, he painted Bertish the Strongman, as if Bertish were a two dimensional version of one of the Midway Gardens winter garden sculptures. The strongman's hieroglyphic stance was surmounted by such a chiseled skull, that the descriptive words become superfluous. And by the end of his Orpheum period, in an era when a monologist in black face could build an act around the then-incongruous idea of a well-dressed Negro, Iannelli's poster for Lew Hawkins made a degrading cultural swipe into something heroic and stylish. Top-hatted, cape trimmed with zipper-like fur, this minstrel looks down at the lobby crowds through a monocled eye while elegantly removing his gloves.

ACADEMIC ANALYSIS

In 1972, Sharon Goldman Rubin wrote her Ph.D dissertation for the University of Minnesota Graduate School. Her thesis, Alfonso Iannelli: The Career of an Artist in the American Social Context 1906–1965, became the first academic study of Iannelli's career. She contrasted his Orpheum illustrations to those of his contemporaries:

"In comparison with American poster artists, Iannelli was even more original. A comparison of his work with the typical poster of the time, exemplified in the World War I posters reproduced in The American Poster, show nothing even slightly resembling it. Howard Chandler Christy, James Montgomery Flagg, Eugenie de Land, J.C. Leyendecker, Henry P. Raleigh, Charles Livingston Bull and Hazel Roberts all produced popular posters with realistic or sentimental figures, naturalistic colors, a variety of type styles (often in the same poster), and little integration of pictorial design with lettering. Although not lacking in commitment, these posters were in no sense simplified, modern designs."

Dr. Rubin examined Iannelli's artistic progression from the time of his arrival in Los Angeles in 1910 to his move to Chicago in 1915:

"Although his work with Frank Lloyd Wright, which began in 1914, helped Iannelli to conquer the possibilities of geometry, he was well on his way to accepting the implications of geometric form before meeting with Wright. In an early essay on the possibilities of commercial art in California, Iannelli analyzed the phenomenon of cubist art. Although people were considering cubism the 'newest thing,' according to Iannelli, it was really the oldest method of expression in the world:

`It began with old Mother Nature herself—have you not noticed that when Nature gets half a chance to express herself, she geometricizes herself—crystalizes herself—in other words conventionalizes herself.'"

Iannelli explained how the Egyptians, the Japanese, the Aztecs and the North American Indians had all utilized the geometric forms of the circle, triangle and square, derived from such natural phenomena as the shape of the sun.

Iannelli felt that the type of modern poster he was creating was able to convey its idea more clearly, and to express its spirit most sympathetically by conventionalizing through geometry:"Every movement that a person makes is traceable to a certain circling action if I may so express it—and if you wish to interpret that action, it is necessary to analyze it, find the basis of the action, the spirit of it, and conventionalize it."

Another important reason that the Orpheum posters rose above the standard set by contemporary illustration could have been the synergy between Iannelli and his new partner.

MARGARET

Margaret Spaulding was a teenaged student of his who possessed an innate talent for illustration and a like-minded interest in Modernism. She had earlier studied in St. Louis and now was living with her parents in Los Angeles, searching, like Iannelli, for a fresh start.

Little is known about their early relationship, but she must have captivated his sense of design as she joined him as an employee or "independent contractor" sometime later in 1913. And, perhaps because Iannelli was still married to Julia at this time, Margaret coincidentally brought in her mother, Pearl, to handle the front-desk duties.

Iannelli continued his Orpheum writings:

"As the experiments progressed, the shapes became simpler, the colors clearer, until the forms were geo- metricized in pure colors....From this point the work was more satisfactory. Careful consideration of colors, their value in depth from the front plane so the poster achieved the self-contained surface and volumes in space....Like the scientist, the artist must start with analysis and determine scientifically the form of his expression once the nature of the medium has been analyzed."

Left unsaid was that he had found a design harmony in working together with Margaret. Whether it was romance that inspired creativity or vice versa, something changed for Iannelli. The new abstracted faces and bodies rendered the performer unrecognizable yet illuminated his stage character with a few deft strokes.

The female faces possessed a charming intelligence not even found in his earlier New York sculptures. So it's quite possible that through Margaret's influence, his oft stated "scientific" search for a new American form had discovered a far more humanist formula. The obvious parallel to the art historian is to the symbiosis of Scotland's Charles Rennie Mackintosh with Margaret McDonald. The Scottish pair shared such a unified design sense that it's often pointless to discern who was responsible for which motif.

Whether or not Margaret was the partner or the student, their results were graphic illustrations boldly reveling

in their two dimensions, yet conveying the exuberance of music, dance and variety acts in a simple visual plane. With these posters, Iannelli felt he had "developed a scientific method of handling this medium to express the vaudeville spirit."A NEW MODERNISM

Iannelli's Orpheum posters gave vaudeville audiences a tangible advertisement for a new Modernism just flower- ing in avant-garde circles. The vibrant, geometricized figures he painted to represent the usual dog acts, comedians and trick whistlers on the circuit lined the theater's lobby with abstractions never before seen by Los Angeles theatergoers.

Iannelli was thought to have created some one hundred posters for the Orpheum Theater between 1912 and 1915. And though his friends urged their publication, he resisted, not wanting to be tainted forever as a "poster man." It was this need to be seen as an original artist that, ironically, buried his future reputation for generations. If only he had allowed his images to multiply throughout the Orpheum circuit or in later publications, the posters he created in that span would have certainly been rediscovered during the boom years of the 1960s. And "Iannelli," so artfully lettered in the corners of each of these lobby sheets, would have meant gold to the later generations of collectors, ranking with A.M. Cassandre, Will Bradley or Alphonse Mucha.

VANGUARD

Iannelli was composed of just the right ingredients of innate talent, a drive to define his place in art and the perspective of an outsider. Unencumbered with tradition, his sense of the "new" was perfectly timed with the marketing of vaudeville for a new century. And though certainly influenced by Wright's architecture and Viennese illustration, his Orpheum work was more the graphic result of a modernist designer's point of view.

Alfonso Iannelli's Orpheum posters place him squarely at the vanguard of American Modernism when the 1913 New York Armory show officially gave birth to the concept of "Modern Art" in America.

Marc Vitali and Yasmin Rammohan contributed to this report.