Geoffrey tracks down a missing fountain, a stockyards priest and mysterious sand dunes in tonight’s edition of "Ask Geoffrey."

Long ago, my significant other and I were on our first date and saw a fountain with figures of birds near Wacker and Wabash. I visited the area recently and the fountain is gone. Where did it go?

-Diane Hansen, Elgin

The fountain she and her date saw was the Children’s Fountain, seen here shortly after it was installed in 1982. It was dedicated to the children of Chicago by then-Mayor Jane Byrne in its original home, as the viewer recalls, on Upper Wacker Drive west of North Michigan Avenue.

The fountain she and her date saw was the Children’s Fountain, seen here shortly after it was installed in 1982. It was dedicated to the children of Chicago by then-Mayor Jane Byrne in its original home, as the viewer recalls, on Upper Wacker Drive west of North Michigan Avenue.

According to Chicago Park District historian Julia Bachrach, the fountain was removed when the Wacker Drive reconstruction project began in 2001. It was taken apart and stored under the Roosevelt Bridge until the Chicago Park District and the Chicago Department of Transportation had the fountain restored and installed in its new location in front of the Chicago History Museum at North Avenue and Clark Street in 2005.

When the fountain was designed in 1982, Mayor Byrne herself selected some of the elements. True to its theme, the fountain features lively children, fanciful animals, and the graceful cranes the viewer remembers spilling into a scalloped granite basin. The fountain is the work of Robinson Iron of Alexander City, Alabama. Robinson Iron bought old Victorian era molds for the project, casting 250 small pieces to assemble on-site. When the fountain was restored, Robinson used the original plans and molds, which meant recasting some pieces at their site in Alabama. Sadly, we weren’t able to catch it in action, but the Children’s Fountain should be turned on soon for the summer.

I recently saw old Field Museum images of the Palos Hills area and a few show large sand dunes! What's up with these? And what happened to them!?

-Emily Long, Rogers Park

The images the viewer is referring to are part of this wonderful set of vintage images the Field Museum has put up for viewing on Flickr.

And the picture does seem almost impossible to believe. Beautiful rolling sand dunes in the southwest suburbs more than 25 miles from the Lake Michigan shoreline where you’d be more likely to find sand dunes – doesn’t that sound too good to be true? Well – it is too good to be true.

We spoke with Nancy O’Shea at the Field Museum who confirmed that the images do not show Palos Hills, but the Indiana Dunes. O’Shea said that thanks to our eagle-eyed viewer the captions have now been corrected.

The mix-up likely happened because at the time these photos were taken in 1916, museum naturalists often took day trips to both the Indiana Dunes and the Palos area to collect materials and take photographs. O’Shea said the glass plate negatives were probably processed at the Museum at the same time and group-labeled Palos without specifying individual locations, thus leading to the mis-identification.

A photo of the Palos Hills area from the same set shows a pretty different landscape from the Indiana Dunes – but these two very different places do share a common ancestor. Both the hilly terrain in the Palos area and the Indiana Dunes are legacies of the last ice age glacier, which receded about 11,000 years ago. The advance and retreat of massive ice sheets carved out Lake Michigan, which formed the dunes. The glacier also pushed rocky rubble into piles called moraines, which became the hills you can see in the vast Palos area forest preserves and elsewhere in the upper Midwest. And of course, Palos Hills and the Indiana Dunes both offer excellent hiking terrain, so that’s another thing they have in common.

Years ago, my family dined at the old Stock Yard Inn. My dad told us about a priest whose portrait hung there. Can you tell me who this priest was?

-Mary Hyland Klausner, Lansing

The Stock Yard Inn was a Tudor-style hotel just outside the famous limestone gates of the vast Union Stock Yards at Halsted and 42nd Street. It was originally a place where cattlemen traveling from the west with their herds would stay and conduct business deals. Naturally, the Stock Yard Inn’s Sirloin Room was the place to go in Chicago for steaks. Diners would select their own steaks and brand their initials into the meat with a hot iron.

The Stock Yard Inn was a Tudor-style hotel just outside the famous limestone gates of the vast Union Stock Yards at Halsted and 42nd Street. It was originally a place where cattlemen traveling from the west with their herds would stay and conduct business deals. Naturally, the Stock Yard Inn’s Sirloin Room was the place to go in Chicago for steaks. Diners would select their own steaks and brand their initials into the meat with a hot iron.

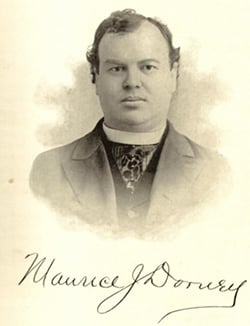

In another part of the Inn, the Saddle and Sirloin Club, featured a gallery of 347 portraits of prominent livestock industry figures. When the Stock Yard Inn closed in the ‘70s, the portraits were moved to the Kentucky Exposition Center, home of the North American International Livestock Exposition. Among them is the portrait of Father Maurice J. Dorney, who was sometimes called the “King of the Yards.”

Father Dorney started St. Gabriel parish in the Irish immigrant neighborhood of Canaryville in 1880. The stone church designed by Burnham & Root opened in 1887 and still stands today. Father Dorney was a gifted speaker described as a friend to both the stock yards workers and the company owners. He helped his parishioners find work in the yards and sometimes mediated disputes between works and employees to avert strikes. He was also a passionate advocate for temperance and worked to restrict saloons in the bustling Canaryville neighborhood. A fervent believer in education, Father Dorney even earned a law degree in 1901 at the age of 50.

The Stock Yard Inn wasn’t the only livestock institution to honor Dorney. The National Livestock Bank gave him a block of stock eventually worth $68,000, which he used to support his church, according to St. Gabriel’s.

Father Dorney died at age 63 in 1914, and his funeral procession was immense. A St. Gabriel’s publication wrote, “From the announcement of his death to the funeral on Wednesday, flags flew at half-staff over the International Amphitheater and the big plants of the yards. In tribute to Father Dorney, on the day of the funeral the stockyard companies suspended business for five minutes." That would have spared 100 hogs at Armour and Company alone, according to a statistic from the Illinois Labor History Society.