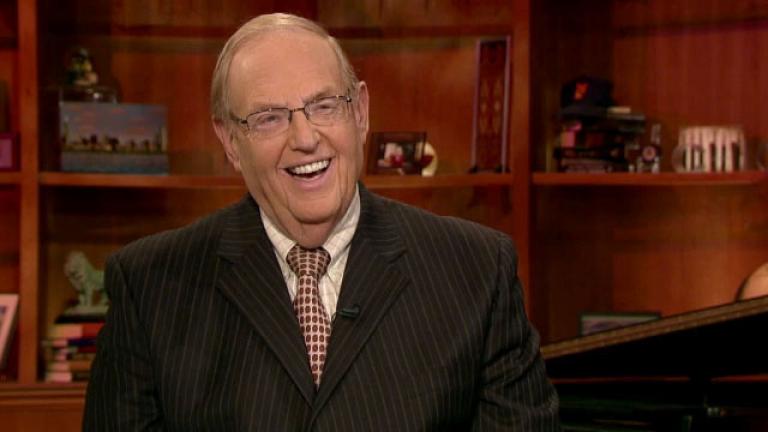

In the 1950s, four people worked together to create the birth control pill. In his new book, “The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution,” Jonathan Eig details how the founder of the birth control movement, a controversial scientist, a wealthy feminist, and a Catholic obstetrician worked together to create the birth control pill.

Eig visits Chicago Tonight to talk about the book and why the pill is one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

Below, an excerpt from the book.

The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution

One: A Winter Night

One: A Winter Night

Manhattan, Winter 1950

She was an old woman who loved sex and she had spent forty years seeking a way to make it better. Though her red hair had gone gray and her heart was failing, she had not given up. Her desire, she said, was as strong and simple as ever: She wanted a scientic method of birth control, something magical that would permit a woman to have sex as often as she liked without becoming pregnant. It struck her as a reasonable wish, yet through the years one scientist after another had told her no, it couldn’t be done. Now her time was running out, which was why she had come to an apartment high above Park Avenue to meet a man who was possibly her last hope.

The woman was Margaret Sanger, one of the legendary crusaders of the twentieth century. The man was Gregory Goodwin Pincus, a scientist with a genius IQ and a dubious reputation.

Pincus was forty-seven years old, five feet ten and a half inches tall, with a bristly mustache and graying hair that shot from his head in every direction. He looked like a cross between Albert Einstein and Groucho Marx. He would speed into a room, working a Viceroy between his yellowed fingers, and people would huddle close to hear what he had to say. He wasn’t famous. He owned no scientific prizes. No world-changing inventions were filed under his name. In fact, for a long stretch of his career he had been an outcast from the scientific establishment, rejected as a radical by Harvard, humiliated in the press, and left with no choice but to conduct his varied and oftentimes controversial experiments in a converted garage. Yet he radiated confidence as if he knew the world would one day recognize his brilliance.

Pincus was a biologist and perhaps the world’s leading expert in mammalian reproduction. In the 1930s, at the start of his professional career, he’d attempted to breed rabbits in Petri dishes using much the same technology that decades later would lead to in vitro fertilization for humans. Then he was young and handsome and possessed of a limitless imagination. He posed for newspaper photographs and boasted to reporters that a new age of human reproduction was on the horizon, one in which men and women soon would employ modern methods to control the process of making babies. Science would lead the way.

But Americans were not ready to hear such things. The press compared him to Victor Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s fictional scientist, who tried to conjure life but accidentally created a monster. Harvard denied Pincus tenure, and no other university would hire him. He was deemed too dangerous.

At that point, a more humble man might have chosen a new line of work. A weaker man might have succumbed to anger or despair. But not Goody, as his friends and family called him, as much for his friendly nature as his middle name. For while Pincus was affectionate and disarming in social settings, when it came to his career he was, as one colleague put it, “a street-fighting Jew.” Getting knocked down was merely the thing that happened before Pincus got up to fight again. When Harvard dumped him and no other job offers arrived, he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, a factory town, where a former colleague from Harvard had offered him a low-paying, low-ranking position as a researcher for Clark University. He worked in a basement lab where dust from a nearby coal bin contaminated his experiments. When he asked the university to provide him a proper laboratory, the request was denied.

Again, he might have quit. Instead, Pincus and one of his colleagues, Hudson Hoagland, did something unprecedented: they launched their own scientific research center. They went door to door in Worcester (pronounced wuhstah, in the local tongue) and the surrounding area, distributing brochures and asking housewives, plumbers, and hardware store owners to contribute—no donation too small—to a new institution they called the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology. With the money they scraped together, they bought an old house in nearby Shrewsbury, where Pincus set up his office and lab in the garage. The operation was so lean in those early years that he cleaned his own animal cages and, at one even lower moment, moved his wife and children into a state-run insane asylum while conducting research there on schizophrenia.

Excerpted from “The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution” by Jonathan Eig. Copyright © 2014 by Jonathan Eig. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.