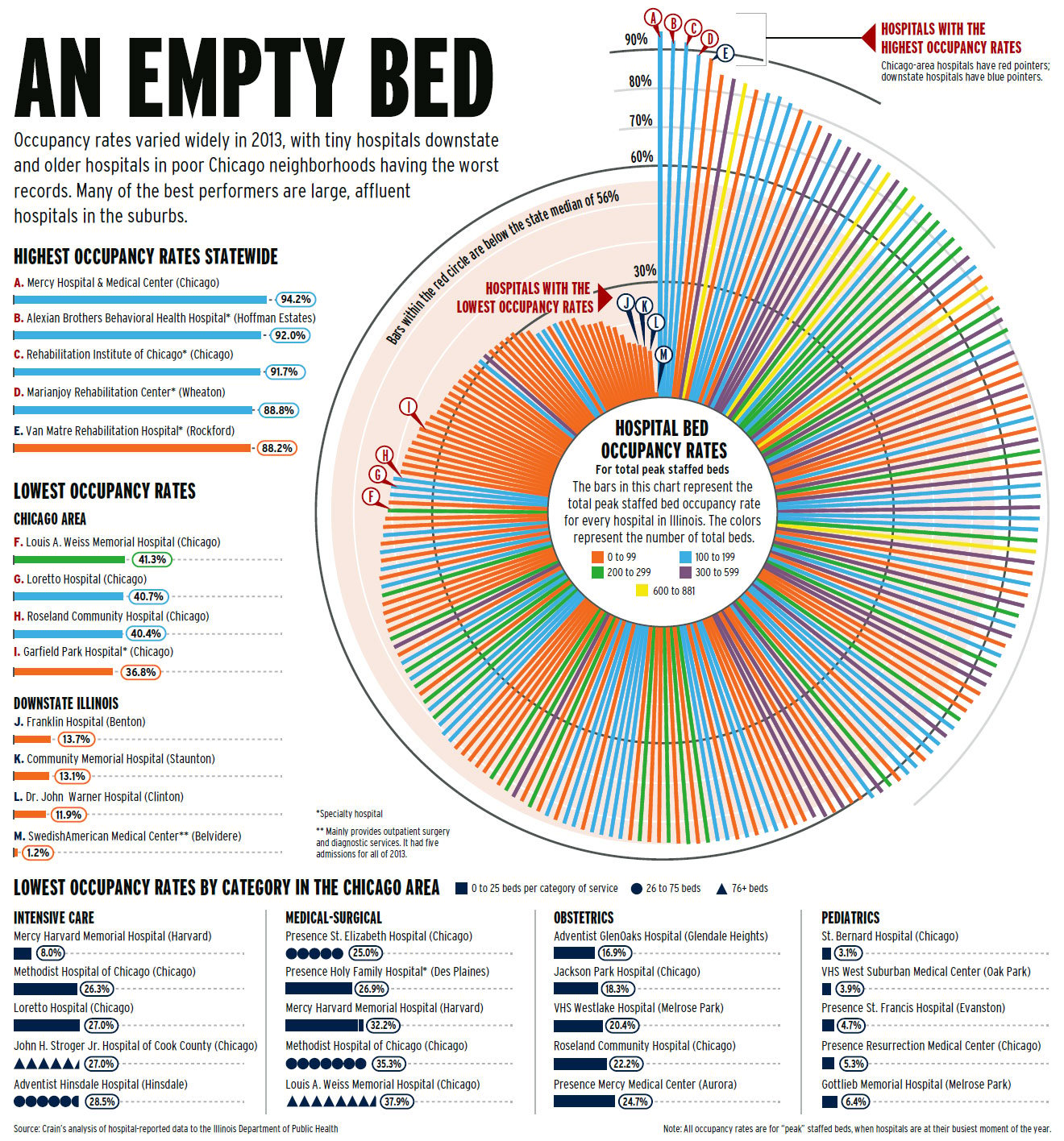

A new report from Crain's Chicago Business found in 2013 nearly four out of every 10 hospital beds in Illinois were vacant. We'll talk with reporter Kristen Schorsch about why there are so many extra beds and what hospitals can do about the problem.

Read an interview with Schorsch.

What did you find that most surprised you?

What I thought was interesting were these clusters of hospitals I found that were half empty and located within a handful of miles of each other. In Chicago, I found three different clusters: one each on the south side, the west side, and the north side, in which the hospitals are roughly half empty, some a little more or less than half, that are all sitting within two to five miles or so, all independently owned. And I thought that was pretty startling, when you look at all the various reasons for what’s happened to these hospitals and the drastic transformation in health care, especially with the Affordable Care Act. There’s a huge push toward outpatient care and keeping people healthy, so they’re not getting sick and ending up with an expensive hospital stay. So I thought those clusters are interesting – is there anyone talking about merging hospitals or sharing services? For example, one hospital can specialize in ICU or difficult surgical procedures, one can be an outpatient center. And that’s happened in other states.

-- Graphic courtesy of Crain's

Why are there so many empty hospital beds?

There’s a host of reasons. Among the biggest one is that for decades there has been a decline in patients using hospitals across country. Particularly in the last few years with the ACA and the big push to keep people healthy with preventative care, to keep health care costs down and to prevent costly inpatient stays. Both government insurers and private insurers want to incentivize doctors and hospitals to keep people healthy, to coordinate their care of chronic things like diabetes. In the past, providers paid per service and there was no penalty for racking up the bill. Now, payers really want to pay to keep people healthy.

There are also advances in technology. You no longer need to go to a hospital for every surgery and stay for five days. There are outpatient surgical centers where you can go home the next day, or even the same day.

Another reason is that, in Chicago specifically, hundreds of thousands of people have left the city. It’s gutted minority neighborhoods near hospitals, which are typically among the largest employers in a neighborhood. They’ve lost patients when people moved.

Also, patients have more choice now. You see things like retail clinics at Walgreens and CVS popping up, where you can go to get a flu shot. You can go to immediate care if you’re sick, you no longer have to go to the ER if you need treatment right away. This has all led to a drastic transformation in how people are seeking care. Hospitals need to find a new identity. They may no longer be a hospital in the traditional sense; they might be transforming into something that’s adapted to today’s environment where people have more choices and doctors are getting paid to keep you out of the hospital.

How do these hospitals stay afloat with so many empty beds?

How do these hospitals stay afloat with so many empty beds?

It’s really tough, especially in small independent hospitals that treat a large portion of low-income and uninsured patients. A lot of hospitals are becoming focused on outpatient care across the board. Whether it’s a huge hospital system or a small struggling system, they know that patients have more choice and that insurance payers want you to keep patients out of the hospital. To survive, you must change your focus to outpatient care by hiring more physicians, putting pharmacies in hospitals so patients can pick up prescriptions there, renting out space to bring in a primary care clinic network – becoming a one-stop shop focused on outpatient care because that’s where the industry is headed. But it’s really expensive to retrofit hospitals to follow the trend of outpatient care. I’ve been talking to a lot of hospital consultants, and “repurposing” is the main theme I kept hearing, but it’s hard, especially for smaller, independent hospitals that depend on Medicaid or Medicare for money. They can’t spend millions retrofitting. Big hospitals do have money to repurpose space.

What is the state’s role in solving this problem?

The facilities board decides which health care projects can go forward in the state, but their hands are pretty much tied. They have a lot of oversight power if you bring them a new project. If you want to add or cut beds or add a new wing, you have to ask them for permission. But after that, they don’t have the manpower or legal authority to say to a hospital, “you’re not using this service enough so close this wing or cut this service, transfer it to a hospital in a neighborhood that needs it more.”

The state legislature passed a law to establish a comprehensive health planner, in Illinois. That person would have been charged with figuring out where exactly we need health care services across the state, but that person was never hired. The law went into effect in 2009, but we've never had a health care planner. There was also a task force the Quinn administration put together that had applied to the federal government asking permission to use Medicaid dollars differently. It wanted to provide hospitals and nursing homes with a $25 million pot of money to close or convert their facilities, and help transform the industry. But now, we have a new governor and it's unclear if the federal government is going to negotiate with the new administration for a waiver. That could be a solution to provide money to help hospitals close or convert. It happened in New York, where they saved struggling hospitals from closing, and others they forced to close for various reasons.

What are hospitals trying to do?

They're trying to bring in traditional outpatient care amenities to hospitals, like having a pharmacy and adding primary care doctors. Most people think of primary care doctors as being out in the community, but now hospitals are partnering with doctors or giving them space in hospitals so you might actually go to the hospital to see your primary care doctor. Some of the hospital CEOs I talked to didn't want to give specifics on what they plan to do to change, but the broad idea about hospitals going forward is that they'll be more like wellness centers where you can go to work out, get a healthy lunch, take classes to learn how to manage chronic conditions. They'll be more of a wellness hub rather than a place you go just when you get sick or need emergency care. They'll be focused more on the needs of patients going forward.

What are the problems associated with closing hospitals?

One of the obstacles is that they are typically one of the largest employers in their neighborhood. They're part of the fabric of the communities where people live. It's also not just hundreds of jobs at stake, but people also have the perception that they won’t have access to care if a hospital closes. It can be an emotional and political battle, there's civic pride involved. There are lots of reasons why it’s tough to change.

Why should people care about this?

People talk a lot about all the waste in the health care system. If you operated a business, would you let half of it sit empty and unused? Wouldn't you, maybe, lease out some space or transform your business so that you use more of space you have? Health care is really, really expensive, and a lot of the hospitals that are the emptiest are also heavily dependent on taxpayer-funded programs, so there's a lot of money at stake. Also, everyone's talking about making health care more efficient and less expensive by keeping people healthy.