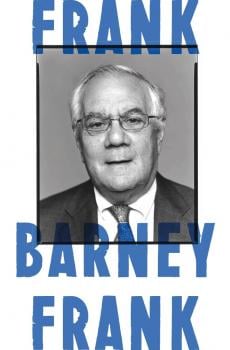

Former Congressman Barney Frank knew two truths at 14 -- that he loved politics and that he was attracted to men. Believing that the two were incompatible, he chose politics. And for a disheveled man who hates campaigning, Frank spent decades representing Massachusetts' 4th Congressional District and rose to become the chairman of the House Financial Services Committee. He came out in 1987, and was the first gay member of Congress to marry his partner. Frank joins us to talk about his colorful career and his views on some local political stories.

Watch a web-exclusive clip of Barney Frank talking about the possible presidential nominees in 2016.

Read an excerpt from his book, Frank: A Life in Politics from the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage.

1.

From Bayonne to Boston

In 1954, I was a fairly normal fourteen-year-old, enjoying sports, unhealthy food, and loud music. But even then I realized that there were two ways in which I was different from the other guys: I was attracted to the idea of serving in government and I was attracted to the other guys.

I also realized that these two attractions would not mix well. At the time, public officials were highly regarded. The president, Dwight Eisenhower, was one of America’s most admired and respected military heroes. I was a homosexual, an involuntary member of one of America’s most despised groups. I knew that achieving success in any area where popularity was required would be impossible, given the unpopularity of my sexual orientation.

If this were fiction, a spoiler alert would now be appropriate, because the story ends with a dramatic turnabout. When I retired from Congress in January 2013, the divergent reputations of elected officials and homosexuality persisted, but with one major difference: The order was reversed. Legal protections for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people were more popular than elected officials as a class. Congress was held in particularly low esteem. While I did not do any polling on the subject myself, I was told that my marriage to my husband, Jim Ready, scored better than my service in the House.

When I first entered public life in 1968, I had to figure out how to keep the public’s negative feelings about my sexual orientation from interfering with my political effectiveness. By the time I’d overcome that obstacle, a larger one appeared: the growing unpopularity of government itself, and the consequent diminution of its capacity to assist the unfortunate. My influence over the political system grew even as the system’s influence diminished. This was good for my self-esteem but bad for my public policy agenda.

This book is a personal history of two seismic shifts in American life: the sharp drop in prejudice against LGBT people and the equally sharp increase in antigovernment opinion. During my six decades in the public realm, Americans have become more accepting of once-despised minorities but also more resistant to coming together through government to improve the quality of our lives. How did this happen and what can be done to further the victories and reverse the defeats?

The many years I’ve spent advocating unpopular causes have taught me that it’s important to begin with your best case, not in the hope of making instant converts but to persuade your audience that there is room for debate about a subject. Fortunately, when it comes to attitudes toward government, that case is even better than a no-brainer—it is a pro-brainer: the story of the millions of children who have been protected from brain damage by federal rules that were adopted over the vehement objections and dire predictions of affected industries.

Before 1970, lead was a major component of paint and gasoline. Its corrosive effects, which are uncontested today, had their worst impact on the very young, impairing in particular the development of the brain cells known as neuroglia. All young people were exposed to lead, and poorer children were the most exposed, since the paint in their homes was more likely to contain lead and to chip, and because they often lived in crowded urban areas adjacent to heavy traffic flows.

Over the objections of private industry, many public health advocates, especially those focused on children, pressed for action. They were successful. The process began in 1970 with the Clean Air Act, which was followed by the Lead-Based Poisoning Prevention Act a year later. A series of amendments and implementing regulations steadily increased the restrictions, culminating in 1978 with a ban on lead in paint, and a statute enacted in 1990 and effective in 1995 prohibiting lead in gasoline.

Critics of government regulation should heed all of this carefully. As the prohibitions came into effect, the incidence of death and illness from lead ingestion dropped drastically. Between 1975 and 1980 and 2007 and 2008, lead levels in children’s blood dropped 90 percent. In 1990, the FDA estimated there were already seventy thousand fewer children with IQs below seventy because of the rules.

The paint and gasoline industries denied that lead was harmful in the amounts present in their products and predicted severe economic harm if they had to remove it. They were never able to explain why banning lead in fact coincided not just with fewer brain-damaged children but also with their own continued prosperity. Lead-damaged brains still exist, sadly, and there is more to be done to reduce the number. But the undeniable fact is that millions of Americans have healthy brains today in large part because, contrary to the old joke, some people from the government did come to help them.

Excerpted from FRANK by Barney Frank, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Barney Frank. All rights reserved.