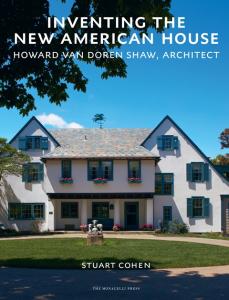

In his new book, Inventing the New American House, Stuart Cohen takes us back to the early 20th century for a look at Howard Van Doren Shaw's architectural footprint on the typical American home.

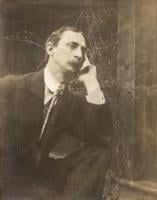

Shaw was a residential architect born in Chicago in 1869. He graduated from Yale University and continued studying architecture at MIT.

Throughout his career, Shaw was largely known for his use of traditional architecture in creating American country homes. He built homes for many of Chicago’s movers and shakers in prosperous communities, including Lake Forest, Ill., the Hyde Park-Kenwood section of Chicago and Lake Geneva, Wis.

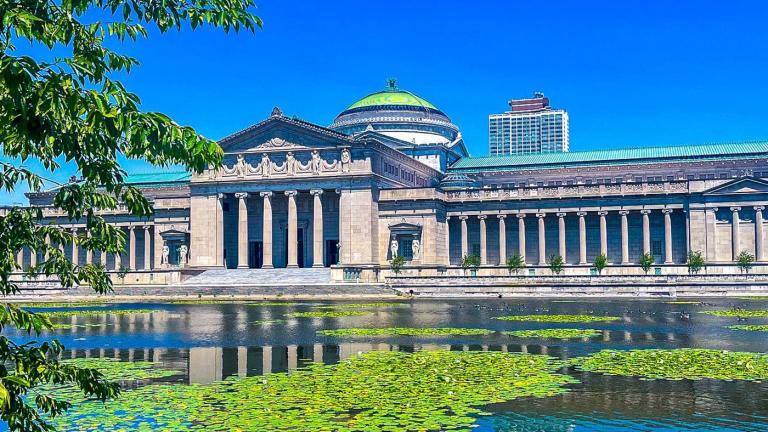

In addition to building homes, he created Market Square in Lake Forest, one of America’s first shopping centers designed to accommodate automobiles. Shaw also designed Marktown, a worker community built within a steel mill.

Shaw was awarded the American Institute of Architect’s Gold Medal shortly before his death in 1926.

View a slideshow.

Read an excerpt from Inventing the New American Home: Howard Van Doren Shaw, Architect.

Howard Van Doren Shaw was one of the best-known country house architects of his day. During his lifetime, he was highly regarded by architectural critics and by his peers. The Architectural Record published collections of his residential work almost every year from 1906 to 1918 with titles such as “Some Recent Country Houses by Mr. Howard Shaw.” Between 1918 and 1926, the journal focused on individual houses and Shaw’s commercial and institutional work. Like that of fellow Chicagoan Frank Lloyd Wright, Shaw’s work appeared frequently in The House Beautiful, which began publication in Chicago in 1898. Shaw’s houses were also used to illustrate contemporary books about residential design. The lakefront house he designed for A. C. Bartlett was published in the March 1916 issue of Country Life in America as one of the twelve best country houses in the United States.

Shaw’s commercial work received comparable recognition. His printing plants for the Donnelley family were lauded as models of progressive design, and his plan for Market Square in Lake Forest, Illinois, acknowledged as the first American shopping center to accommodate automobiles, was illustrated in The American Vitruvius: An Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art, Werner Hegemann and Elbert Peet’s monograph on artistic urban design.

In 1926, the year of his death at the age of fifty-seven, Shaw was awarded the gold medal of the American Institute of Architects “in recognition of a significant body of work of lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture.” Shaw was the ninth architect and only the fifth American to be recognized in this way.

Shaw practiced principally Chicago and vicinity from the early 1890s to the mid 1920s, an expansive period in American architecture that encompassed the great wealth of the Gilded Age, the adoption of Beaux-Arts classicism as the image of civic architecture following the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the invention of the skyscraper, and the emergence of modernism. Born in 1869 into a prosperous Chicago family and educated at Yale University and MIT, Shaw drew upon his youthful friendships and personal connections as a client base to generate a substantial portfolio of country houses, country clubs, and commercial buildings.

In his obituary of Shaw in The Architectural Record of July 1926, Thomas Tallmadge, a Chicago architect, historian, and author, wrote, “Perhaps one might say of him, he was the most rebellious of the conservatives and the most conservative of the rebels.” To understand what Tallmadge meant, we need to understand who these rebels were, what they were rebelling against, and what Shaw was conserving. By the 1890s, many prominent American architects were being trained in the classical tradition, either at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris or in one of the handful of American architecture schools, where the curriculum was patterned on the methods of the Ecole, which relied on specific historical precedents. It was the rigidity of this requirement and the limitations of classical symmetry that some architects rebelled against.

Tallmadge’s rebels were Chicago’s commercial architects, who pioneered the design of tall office buildings and Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School architects, who were designing houses. Shaw was exploring many of the same architectural ideas as the Prairie School architects, but he did so within the forms and associative meaning of traditional architecture.

Shaw, like Wright and the other Prairie School architects, shared and explored the architectural ideas that helped transform twentieth-century architecture. H. Allen Brooks touches on this subject in The Prairie School: Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwest Contemporaries, when he discusses the architects who had studios in Steinway Hall, an 1896 piano showroom and office building designed by Dwight H. Perkins. They were the core of a group of friends who lunched together to discuss architecture. The group, which included Shaw, was referred to as “The Eighteen” by Frank Lloyd Wright in his autobiography. Wright, who portrayed himself as central to this group, is often credited with the development of major architectural ideas that defined twentieth-century architecture—the continuity of interior spaces, the relationship of a building to its site, the dominance of horizontality in the composition of a building’s mass, and the visual connection of interior and exterior spaces. In reality, these ideas were shared by the group and incorporated in the designs of many of these architects in a variety of ways.

Excerpted and reprinted with permission from Stuart Cohen, Inventing the New American House, Monacelli Press.