The story of the Civil War has been told from many different perspectives. Here on PBS, Ken Burns' now famous series used both historians and personal diaries and letters to tell the epic story. And now the journals of another Civil War veteran have come to light and are the basis of an exhibit at the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in Chicago.

As Eddie Arruza explaines, the journals went unnoticed for about century but now are seen as an historic treasure trove.

TRANSCRIPT

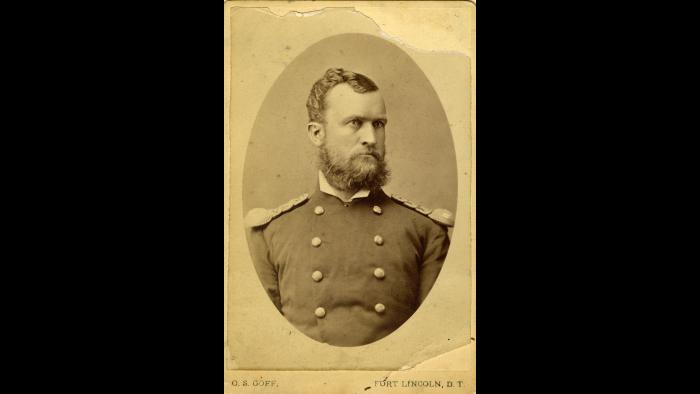

Eddie Arruza: For much of the 19th century, the United States was a nation at war. Many of the conflicts were regional, but the most significant one involved the country at war with itself. And if there was one man who personified the 19th century American soldier, it was Erasmus Corwin Gilbreath.

Kenneth Clarke, President and CEO of Pritzker Military Museum and Library: Erasmus Corwin Gilbreath was a man who grew up in Valparaiso and who as part of a volunteer infantry during the Civil War, fought in pretty much every major battle there was during the Civil War.

The thing that distinguishes him is he actually documented all of that activity from the end-of-the-rifle perspective of what happened at the end of the war.

EA: Erasmus Corwin Gilbreath was born in Ohio but his family moved to Indiana when he was still young. He was 21 when the Civil War began and he immediately answered the call to serve by helping muster the 20th Indiana Volunteer Regiment. Within months Gilbreath was on the battlefield for the first of many times. And he began documenting what he witnessed.

... To help me make a connected story with the hope that it may be slightly interesting, I've tried to relate my own experiences and to tell what I saw so that it is all the more personal than a general history of either the 20th Indiana volunteer infantry or of the events in which we took our part.

– Erasmus Corwin Gilbreath

KC: Some of his words are the definitive words of what happened during those actions. There's nothing like his writings detailing what that group went through during the war.

EA: Gilbreath's story – based on his many journals – is the subject of a new exhibit at the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in downtown Chicago and an accompanying book called Dignity of Duty. (Read an excerpt of the book below.) But none of it would have come about had it not been for Gilbreath's great-granddaughter, who rediscovered the journals that for the better part of a century were housed at the Detroit Public Library.

KC: We were just taken with the quality of his writing and the rich history that was contained in them. He was kind of like a Forrest Gump of 19th century American history, quite frankly, the things that he saw, the people that he met, you could very easily make a play or movie out of these journals.

EA: For the exhibit, The Pritzker Museum has found and in some cases recreated a number of artifacts related to Gilbreath, including some of the medals he received, a replica of his final military uniform, and even the weapons and munitions he would have used. But the exhibit springs from his own words and it includes an audio tour where visitors can he hear a present day military man voice the words of the Civil War veteran.

Here is what Gilbreath wrote after being seriously wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862.

I tried to crawl off, but that was too painful. The ball had taken off the entire front of the tibia of my right leg at the point about two inches above my ankle joint, and every movement was painful indeed. I laid there on the field from about 2 p.m. until 8 or 9 o'clock at night. At last I heard a voice way off to the rear calling my name. It was pretty husky work, but I stopped my grateful tears and, wetting my throat as well as I could, gave back a weak yell. He called again and up came John French of company I, a sergeant who with others was looking for me.

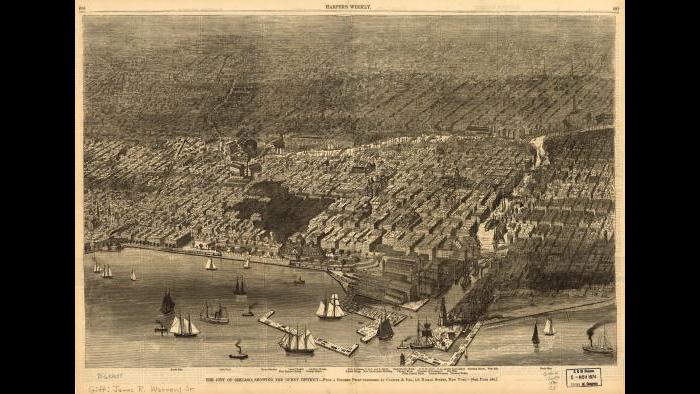

EA: Gilbreath took part in 12 Civil War battles including Gettysburg. And while some of his military brothers died on the field of battle, he survived to write about it all in detail. Gilbreath's military career didn't end with the Civil War. He played major roles during the Reconstruction era, was stationed in Chicago for several years, was witness to the so-called American Indian Wars, and in his late 50s shipped off to Puerto Rico to fight in the Spanish-American War.

It was there he died on Aug. 22, 1898, at the age of 58, of what was officially deemed apoplexy. In modern day parlance that could have been anything from an aneurysm to a heart attack to a stroke. But his many detailed journals lived on and are now shedding new light on one warrior's eyewitness account of history as it unfolded.

KC: What I noticed is that these writings actually go over into that literary prowess that you wouldn't expect a field officer to have any business writing like that.

You start to realize when somebody writes about that stuff that the toll of war on human beings on a very personal level. Then it was – the medical care wasn't what it is now. But I would say that nowadays the equivalent of it is the mental toll of war, and you hear a lot about PTS and people dealing with the aftermath of war. These kinds of things, these kinds of very personal stories, are things that you find in Gilbreath's writing as well.

EA: A story of valor, sacrifice and above all dignity. For Chicago Tonight. I'm Eddie Arruza.

Dignity of Duty: The Life and Times of Erasmus Corwin Gilbreath will be on display at the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in downtown Chicago through next May. And this November you can catch the 25th anniversary, digitally remastered presentation of Ken Burns' The Civil War right here on Channel 11.

Read an excerpt of Dignity of Duty:

Chapter 1: Raising & Organizing the Regiment

Book cover of 'Dignity of Duty.' (Courtesy Pritzker Military Museum)

Book cover of 'Dignity of Duty.' (Courtesy Pritzker Military Museum)

In a country like ours was in 1861, accustomed to a long series of years of peace and composed of a people not at all habituated to the performance of any military duty, the mobilization of a large force in a short time was a problem not easily solved.

History relates the story of the arousing of public sentiment in the North on the attempt of the Southern States to withdraw from the Union. I shall confine this narrative to the more personal story of the raising of the Volunteer Company and the organization of the Regiment to which I belonged, the 20th Indiana Volunteers, and shall follow this with an ac-count of the Regiment’s experiences, the whole intended to be my own per-sonal experience as well as the movements of the Regiment during the War.

The story of raising one Company or one Regiment from county dis-tricts was like the story of each one so raised.

In 1861, I was living at Valparaiso, the County seat of Porter County, Indiana. Like the majority of the great mass afterwards formed into the gigantic Volunteer Army of the War of the Rebellion, the people of this county were living with no thoughts of the possibility of such events as came to them in the following four years.

We, who became members of the Volunteer Army from that county, were entertaining only hopes for the future bounded by friends, neigh-bors and our immediate surroundings.

I wished only for a light which would guide me to a way by which I could care for my mother, her daughter and other son.

I had begun to study law in the office of Mark L. DeMott, Valparaiso, Indiana, who later became Colonel in the Volunteer and held many offices including that of member of Congress. My law study had progressed to such an extent that I had hopes of being admitted to practice at the Bar after a few more months’ work.

The War alarm was sounded. President Lincoln called for 75,000 Vol-unteers. I paid little attention to the matter except to keep posted by the newspapers as to the excitement of the country, and certainly had little thought of going into the Army myself.

On the 4th of June, 1861, J. W. Lytle, a personal friend of mine and of my mother, came to Valparaiso from a visit to his old home and the home of his father at Logansport, Indiana. At the latter place, he had come in contact with W. L. Brown, a Mexican War Veteran, and had been asked by Brown to help raise a Rifle Regiment which Brown had authority for from the Secretary of War at Washington.

Lytle had been a Civil Engineer and I had worked under his orders for some time while he was building a railroad from Logansport to Valpar- aiso, Indiana. I met him quite by accident, as he stepped off the train at Valparaiso. His first exclamation was, “You are just the one I wanted to see, for you are going to War with me.” I was surprised, and refused. I pass the personal and affecting incident following his arrival, and say that on the 5th of June, Mr. Lytle and myself begun work raising a Company.

To do this, we simply rode through the country, informing everyone of our desires and sending out information that we had fixed on the 15th day of June for a grand meeting at the courthouse for the purpose of organiz-ing a Company for the War under the call of the President for 75,000 men.

On the day fixed, the 15th day of June 1861, nearly everybody in the county came to Valparaiso, and so great was the enthusiasm that, in an hour after the meeting was called, we had enrolled 150 men or 50 more than we needed. So little did we know about military affairs that we sup-posed we could keep all of these men with us.

When the time came at that meeting for the selection of Officers, everybody was good-natured and Lytle urged me for Captain while I urged him to take it. Either one of us would have been satisfied with any position in the Company.