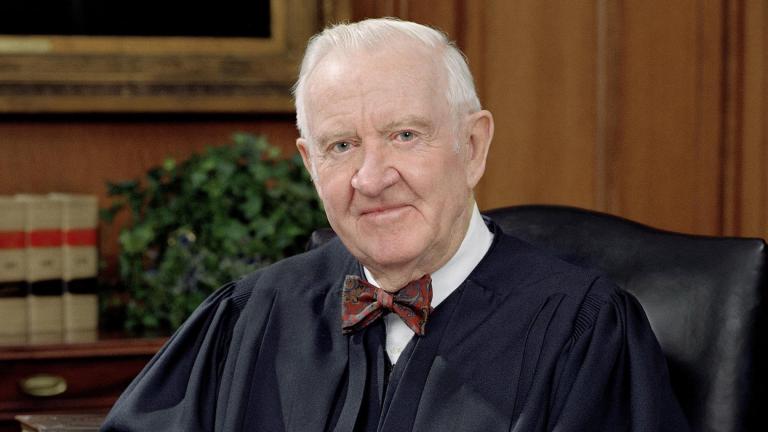

In 1969, a distinguished but hardly famous Chicago attorney named John Paul Stevens was appointed to represent the Greenberg Commission, which was investigating charges that two members of the Illinois Supreme Court had been bribed by a bank that was involved in a case before the justices.

Stevens’ vigorous prosecution of the two justices and the commission’s subsequent condemnatory report caused the men to resign and gave Stevens a national profile.

By the end of 1975, Stevens had been appointed as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. When he retired in 2010, Stevens was the third-longest serving justice in the nation’s history.

The new documentary "Unexpected Justice: The Rise of John Paul Stevens" tells the story of somewhat forgotten scandal and its effect on Stevens’ career.

Below, a Q&A with the film's co-director Greg Jacobs.

![]()

How did this project come to be?

It started with Ken Manaster, who was part of Stevens’ team as a 27-year-old in 1969. Decades later, he wrote a book about that summer and that case. He had always wanted to turn it into a documentary, to see if the story told that way. He, through roundabout means, managed to get in touch with us. This was a story that we had never heard of. You kind of say, “Boy, I thought knew about all of the Chicago scandals!” It seemed really intriguing, and the ball got rolling from there. It’s been a long process for not a long documentary, but it’s been really rewarding. It’s a fun story with surprisingly significant consequences.

There are lots of archival newspaper articles, photos, and video in the film. How did you assemble it all?

The first gift is that Ken must be a pack rat. He had saved a lot of the press clippings from that summer, he had all the documentation from the case still. That gave us a huge head start in that we had the depositions and the articles and all that. This case was so heavily covered that there was no shortage of articles. It amazes me, you see the headline “Man Walks on Moon” or “Astronauts Blast Off for Moon” or something like that, and right above it, there’s a headline about the Greenberg Commission. Also, our producer, Rachel Pikelny, she is a fiend for this kind of archive work. She managed to track down great clips of Sherman Skolnick [a local activist who initially brought the corruption charges to the attention of a reporter] and a lot of other archival material that helped us bring the story to life.

Skolnick is described in the film as a “gadfly” in the film – was he very successful?

As Ken says in the film, even a stopped clock is right twice a day. I think he was just that guy – every city probably has this guy or woman, or should – that is just a permanent skeptic about everything and everyone in power. He didn’t just feed newspapers conspiracy stories at this point in his career. He actually dug into the archives and did hard work, which I imagine was not easy for him at the time because he was in a wheelchair. I think his success rate was probably not very high, but when he did succeed, like in this case, it was a big target.

Taking on these judges is described as a “suicide mission” for an attorney. Why did Stevens do it?

One of the things that strikes you looking at his career and having met him now, for as brilliant a mind as he is, he is an extraordinarily humble person. I think for him it was just genuine – there was no political calculation, no ambition attached to this necessarily. It was just, I’m a lawyer, I’ve been asked to do this, and it’s my responsibility to the bar to do this. He says he got the call while he was outside playing baseball with his kids, and said alright, I’ll do this. It doesn’t sound like there was a ton of calculation.

And he was already in, what, his 40s or 50s at this point?

Yeah, it’s not like, “and then stepped up this young lawyer…” He was 49! And he was already in the middle of a distinguished career, but a distinguished and fairly low-profile career. People knew him as a brilliant lawyer, and he’d been involved in some fairly prominent cases, but I don’t think he was on any shortlist for a judgeship, or certainly the Supreme Court.

In the film, you say the public was very skeptical of the commission and almost expected it to do nothing?

Sure, and a lot of that was also fanned by Skolnick. At the time you have a competitive press, there are a number of newspapers fighting over the story, and this was great fodder for them. Obviously Chicago was not a stranger to corruption and scandal. People figured this was putting a fox in charge of the henhouse, having lawyers investigate the people who are not quite their bosses, but are the people they need to appeal to: judges. I don’t think anybody expected anything to come of it. It’s a tribute to the lawyers who made up the commission itself, the five attorneys, and obviously to Stevens, that they were able to get to the truth.

The commission issued a scathing report against the two justices. Was that a surprise?

I think it started to turn midway through the hearings, which took place over about a week and a half. People assumed it would be a whitewash, and then as they saw the judges under investigation – these were serious questions being asked, and they were struggling. People started to see the commission was really doing serious work. By the time the report came out, newspapers were already calling for these justices’ resignation. It was probably only a matter time for them to actually step down once the report came out. I think there was something about the tenor of the times. There was a growing sense of assault on institutions that had previously been fairly immune. I think not many people gave much thought to the Illinois Supreme Court, but assumed it was above corruption. To have that fall under suspicion, it was one more institution that’s now suspect. And that’s part of what made people say that this is something serious.

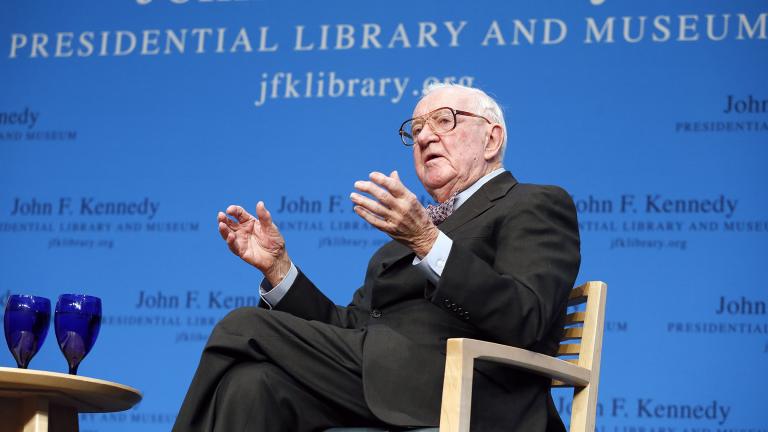

What was it like interviewing Justice Stevens?

It was definitely intimidating, in that he is clearly, even at 95, such an incredibly sharp mind. I think we say in the film he had the highest GPA ever in the history of Northwestern Law at that point. Clearly, this is somebody who is brilliant. But he is the most gentle and thoughtful and self-effacing and humble person you can possibly imagine. There’s not a trace of arrogance to him. He immediately puts you at ease in that regard. I just tried to ask questions and not make a fool out of myself, and he gave some wonderful answers.

It seems like Stevens and other people you interviewed have really strong memories of this case.

It’s sort of incredible how much of a formative thing this case seems to be for a number of people in the film. First of all, Stevens was clearly profoundly affected by his work that summer in a number of different ways, not only in his career, but in how he approached legal issues. It’s still a very strong memory for him. Obviously, Ken’s legal career was set in motion that summer. Ed Pound, the investigative reporter [who first broke the story after Skolnick shared evidence with him], said it was the best story of his life. It was probably a high point in Sherman Skolnick’s career as well. Because there have been so many scandals that are more familiar to us now in the intervening years, this was kind of a forgotten story. That was one of fun things, was that this was really a major, major story and an interesting chapter in Chicago history.

Video: A trailer for "Unexpected Justice."

Unexpected Justice: The Rise of John Paul Stevens from Siskel/Jacobs Productions on Vimeo.