The political mobilization of gays and lesbians in Chicago relied in part on a fragile alliance with the city’s black community. That’s just one of many fascinating revelations captured in the book, “Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics” by Timothy Stewart-Winter, a University of Chicago alumnus who currently teaches history at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey.

“Queer Clout” follows the political rise of Chicago’s LGBT community, from fighting against police raids of the city’s gay bars to being courted by the city’s first African-American mayor, Harold Washington, and then decades later by Barack Obama as he climbed from being a little-known state lawmaker to ultimately becoming the nation’s first black president.

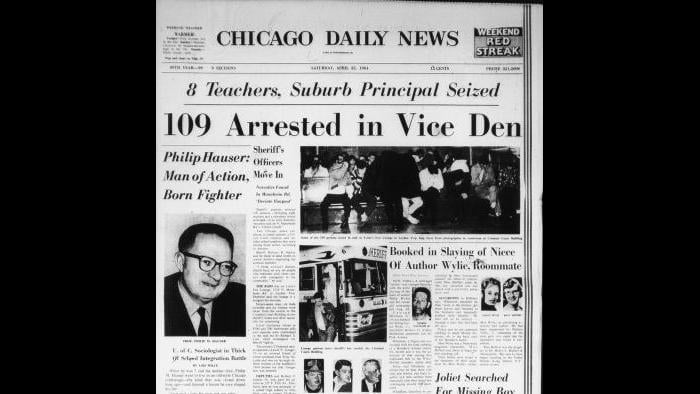

"Chicago is actually more representative than New York and San Francisco of the trajectory of gay politics," said Stewart-Winter. "Folks moved to Chicago from all over the Midwest, but it's not the kind of national mecca that New York and San Francisco are like. And so, gay bar raids went on longer here, gay people had to have more allies in order to win clout in City Hall than in other places."

Read an excerpt of "Queer Clout."

INTRODUCTION

In 2013, the chief justice of the United States suggested that the gay-rights ‘‘lobby’’ was so ‘‘politically powerful’’ that gay couples denied equal access to marriage should not be considered a disadvantaged class deserving protection from the courts. And yet, only fifty years ago, gays and lesbians were social and political pariahs, facing harassment wherever they gathered. This book traces that trajectory—from the closet to the corridors of power—and chronicles the rise of gay politics in the postwar United States.

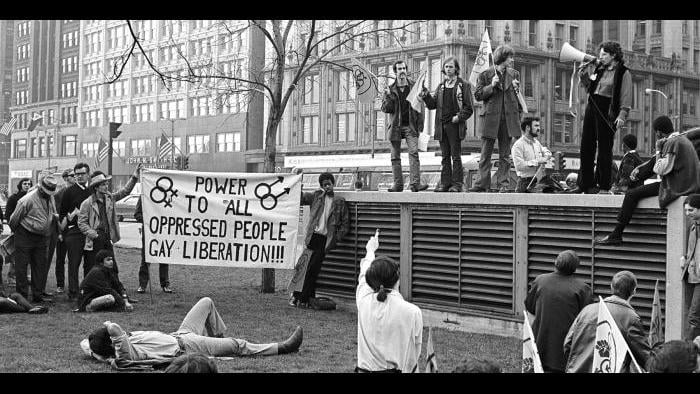

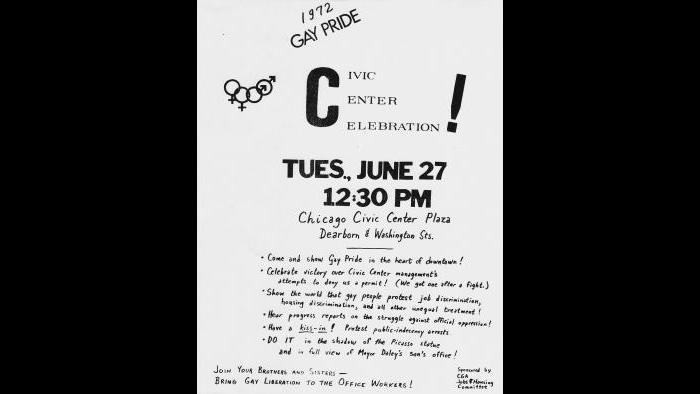

The path of gays and lesbians to political power led through city hall and developed primarily in response to the constant threat of arrest under which they lived. Their eventual victory over police harassment, secured by allying with other urban residents who were policed with similar vigor, especially African Americans, was the prerequisite for their later triumphs. By the late 1980s, in cities where politicians had only recently sought political advantage from raiding gay bars and carting their patrons off to jail, gays and lesbians had acquired sufficient power and influence for elected officials to pursue them aggressively as a potential voting bloc—not least by campaigning in those same bars. Gays now had clout.

Gay migration to cities was a major feature of postwar urban life, one that consequentially shaped urban liberalism. After World War II, unprecedented numbers of e´migre´s from smaller cities, towns, rural areas, and suburbs left their families of origin and joined urban gay society, where they learned they could find both anonymity and community. As Carl Wittman wrote of San Francisco, in the most influential manifesto of the gay-liberation movement, ‘‘We came not because it is so great here, but because it was so bad there.’’ In subsequent decades, the gay-rights movement flourished and drew in predominantly white and middle-class city dwellers. As urban gay communities swelled with newly out and newly arrived gay people, their desire for recognition and their need for government protections began to realign the political views of a small but growing minority. In growing numbers, gays and lesbians chafed against their outcast status; they demanded that local government, and particularly the police, treat them as rights-bearing citizens.

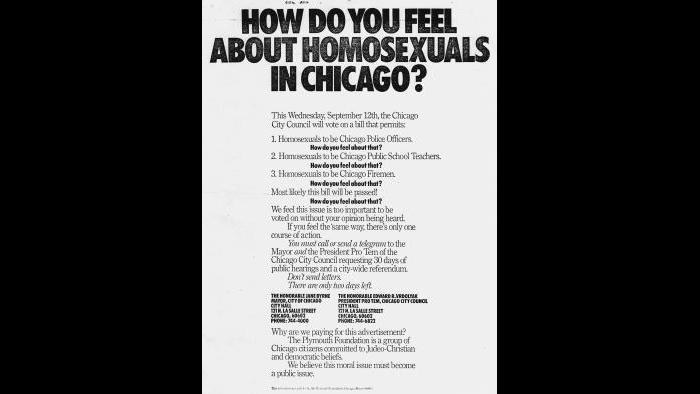

The rise of the gay movement in postwar America was shaped by a liberal faith in civil liberties as well as, in the 1960s, by the Vietnam-era antiwar movement, the hippie counterculture, and the rebirth of feminism. In Chicago, where gay mobilization was weaker and routine police raids persisted longer than in the vanguard cities of New York and San Francisco, gays and lesbians joined an emerging coalition. A key factor enabling them to challenge police harassment successfully was the example of demands by blacks for police reform, and what enabled gays and lesbians to gain power—a toehold in city hall—was the emergence of progressive, black-led local electoral coalitions. The gay movement flourished in the soil of urban politics not only because gay people were concentrated in major cities but also because it was in big-city municipal government that African Americans and their white allies criticized police practices, demanded reform of the criminal-justice system, and called for inclusion and tolerance as governing ideals.

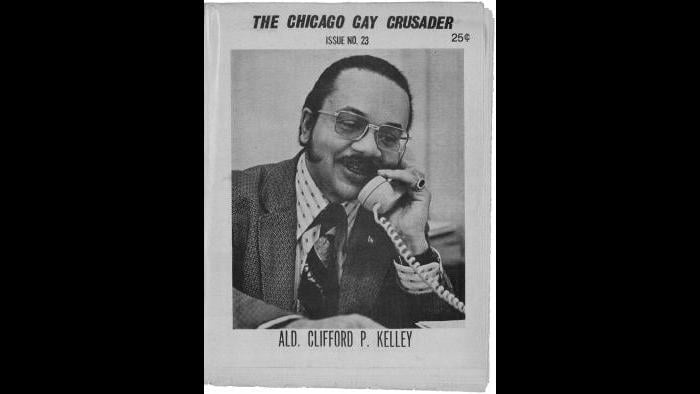

As the Democratic Party began slowly to recognize the demands of blacks and Latinos, women, and gays and lesbians, black elected officials were instrumental in cementing the importance of gays and lesbians in the new electoral coalition. The black civil rights movement provided gays not only a model but also new opportunities to gain visibility and influence at the municipal level, as black and white liberals broke open urban machines and rejected traditional political structures they viewed as corrupt and unfair. As police harassment diminished and as more gay people came out and realized they had no recourse if they were fired for being gay, they again turned to the civil rights model developed by African Americans to seek legislation to protect them, and to black elected officials to defend their civil rights. For reasons of both pragmatism and principle, African American big-city mayors in particular sought to cultivate the gay vote.

This book traces the political effects of a neglected convergence that saw blacks and gays constitute an increasing share of the urban population after white flight to the suburbs. In this period, gays and lesbians asserted a ‘‘right to the city’’ in a way they had not done before. They signed petitions, wrote articles, asked to meet with police commanders, filed lawsuits, and marched in the streets. In urban America, beginning in the early 1960s, gay activists learned from the tactics of African Americans who challenged police brutality through protests and lawsuits. In Chicago, as black and white liberals acquired influence in the 1970s, gay activists joined a coalition that resisted police extortion, spying, and surveillance. Driven together by their shared concern with combating the overzealous activities of law enforcement, black and gay activists sometimes found common cause with one another in the face of police harassment. These fragile alliances ultimately foundered in part because, ironically, in the very years when policing and punishment in black neighborhoods began to increase, the policing of predominantly white gay establishments and neighborhoods became far less systematic.

Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics, by Timothy Stewart-Winter. Published by the University of Pennsylvania Press ©2016

Related

LGBT History Focus of New Children’s Book

LGBT History Focus of New Children’s Book

October 2015: There's a new book for kids detailing the historical contributions of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people to the LBGT movement, which also benefited society, science, the arts and the civil rights movement. The book's author, Jerome Pohlen, joins us.