Ever wonder why Hollywood's married sleuths Nick and Nora Charles retired to separate beds after their comic adventures? We have film censors to thank—or blame—for those twin beds.

For much of filmmaking history, government entities sliced and diced the movies as they saw fit, cutting out profanity, violence and obscenity until the movies were squeaky-clean. But did this silencing of the salacious protect Americans or control them?

"Film started pushing and expanding what could be discussed in public," author Jeremy Geltzer said.

His new book explores more than a century of censorship in cinema and how modern versions of censorship shape media today. It's called "Dirty Words and Filthy Pictures: Film and the First Amendment."

Chicago played a key role in this history, both as a film hub and in the city's choice of chief censor.

"In 1907 the city of Chicago passes the first censorship law that's systematically enforced," Geltzer said. "Chicago is the first city to really crack down on film, and they put the perfect censor in charge: Major M.L.C. Funkhouser. He was one of the strictest censors in the country. If he saw a glimse of ankle, the film was banned. A couple dancing closer than six inches together? That was cut."

But Funkhouser's standards were very arbitrary, said Geltzer. "It was whatever rubbed him the wrong way."

And his penchant for cutting soon expanded beyond film. "He started censoring everything he saw," said Geltzer. While visiting the Art Institute with his family, Funkhouser demanded that an 18-foot bronze sculpture be immediately removed from the museum because of nudity. He settled on draping the artwork when it was deemed too heavy to move.

"That lead to his downfall," said Geltzer. "He had gone a little too far."

Below, a timeline chronicling the history of film censorship in the U.S.

Read an excerpt: Dirty Words and Filthy Pictures

Chapter 18: Is Censorship Necessary?

The story of film and the First Amendment charts a steady course toward creative freedom. Within one hundred years, motion pictures developed from a fairground attraction into an art form, and from a revolutionary technology into an industrially produced mass media. More accessible to large audiences and more powerful in delivering a message than any previous medium, the movies quickly transcended their origins as a penny-parlor amusement to become an important cultural influencer.

During the first decade of the twentieth century a web of local and regional film censors crisscrossed the country. These regulators intended to protect the morals of their communities, but the effects of their activism created a patchwork of inconsistent standards. Harry Aitken, President of the Mutual Film Corporation, was one of the first film producers to challenge the state’s authority to censor and delay his pictures. But Aitken was less of a First Amendment warrior than a practical businessman. As he saw it, regional censorship was holding up his company’s time-sensitive newsreels. He questioned the state’s authority to regulate motion picture content. By 1915 Aitken had an answer, but it wasn’t the result he had hoped for.

During the first decade of the twentieth century a web of local and regional film censors crisscrossed the country. These regulators intended to protect the morals of their communities, but the effects of their activism created a patchwork of inconsistent standards. Harry Aitken, President of the Mutual Film Corporation, was one of the first film producers to challenge the state’s authority to censor and delay his pictures. But Aitken was less of a First Amendment warrior than a practical businessman. As he saw it, regional censorship was holding up his company’s time-sensitive newsreels. He questioned the state’s authority to regulate motion picture content. By 1915 Aitken had an answer, but it wasn’t the result he had hoped for.

In Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio the Supreme Court unanimously held that motion pictures did not qualify for First Amendment protections. The Court’s reasoning hinged on two points. First, “the exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit.” States had long regulated--and citizens had long accepted--standards governing stage productions, parades, fairs, and circuses. Second, the Court saw motion pictures as “vivid, useful and entertaining no doubt, but…capable of evil, having power for it, the greater because of their attractiveness and manner of exhibition.” See Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, 236 U.S. 230, 244 (1915). Perhaps it was because the silver screen transfixed audiences with a hypnotic influence unlike any other medium of expression, that the Court found it well within the state’s rights to regulate.

With a legal framework in place to support state censorship, leading film industry moguls rethought their approach. Motion picture producers and distributors turned to self-regulation in an effort to avert governmental interference. Studio executives created an organization, the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors Association, (MPPDA later to become the Motion Picture Association of America, MPAA). The MPPDA appointed a Washington insider, former Chairman of the G.O.P. and Postmaster General Will Hays, to lead a preventative anti-censoring effort. The initial solution proposed by the Hays office self-censorship in the form of a list of Don’ts and Be Carefuls. The “Don’ts” included profanity, nudity, traffic in drugs, white slavery, sex hygiene and venereal diseases, scenes of actual childbirth, or willful offense to any nation or race. The “Be Carefuls” revealed an even more granular listing of 26 sensitive subjects to avoid on screen. But the voluntarily verboten matters did not meet satisfy municipal censors. As the Jazz Age thrived, the Hays Office had little effect.

The MPPDA’s influence over movie content began to change when Hays hired Joseph Breen as an administrator in the West Coast Office in 1931. Taking the place of the “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls,” a production code was hammered out. Still, enforcement was lax until Breen took control of the newly formed Production Code Administration in June 1934. Under Breen, gangster dramas like Scarface were squelched and cunning sexual innuendoes from the likes of Mae West were silenced. Hollywood filmmakers were forced to convey naughty moments with elliptical references: a tight embrace, a fade to black, a train going through a tunnel.

On the one hand, the production code limited the subject matter and maturity of the movies. On the other hand, the code sought to preempt state censorship and avoid overlapping overseers of content. By joining the MPPDA, studios sacrificed autonomy to avoid governmental regulators. In exchange, the MPPDA lobbied in Washington to maintain the film industry’s independence. This symbiotic relationship helped studios position their products as safe investments for financiers. Challenges to the status quo would not come from within the studio system: it was up to independent and international filmmakers to fight for film’s First Amendment rights.

The showdown arrived in 1952. Roberto Rossellini’s The Miracle played in Italy without incident but once it arrived in the United States, censors sharpened their scissors. New York’s board of regents banned the picture, but domestic distributor Joseph Burstyn championed the short film up to the Supreme Court. In a verdict that was impossible to predict, the Court reversed its long held position. Thirty-seven years after excluding film from the constitutional guarantees of free speech, the Miracle decision brought movies under the First Amendment. Wrote the Court, “It cannot be doubted that motion pictures are a significant medium for the communication of ideas. Their importance as an organ of public opinion is not lessened by the fact that they are designated to entertain as well as inform…That the production, distribution, and exhibition of motion pictures is a large scale business conducted for private profit does not prevent motion pictures from being a form of expression whose liberty is safeguarded by the First Amendment.” See Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495, 501–502 (1952).

The Miracle decision was the first step towards the freedom of the screen in the coming years motion picture content would become increasingly daring. Even greater legal challenges lay ahead.

Excerpted and reprinted with permission.

More book segments from "Chicago Tonight"

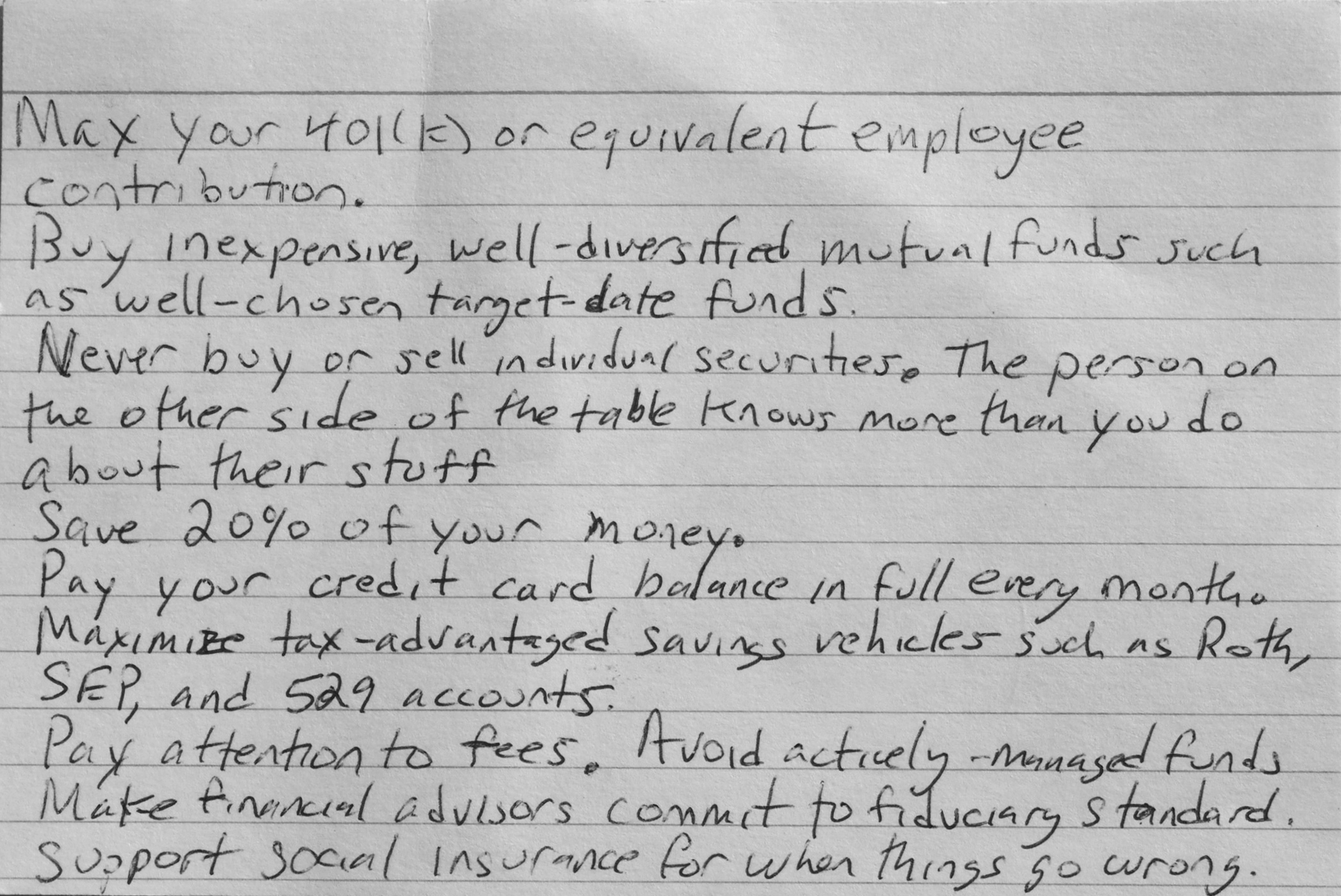

Why An 'Index Card' of Financial Advice is All You Need

Why An 'Index Card' of Financial Advice is All You Need

Jan. 12: In 2013, Harold Pollack came up with a nine-point index card of common sense financial advice after a conversation with journalist Helaine Olen. Now, the two have expanded the card slightly into a book designed to put the average person on the road to financial well-being.

Author Irvine Welsh Takes Readers for 'A Decent Ride'

Author Irvine Welsh Takes Readers for 'A Decent Ride'

Feb. 29: Best known for his 1993 novel "Trainspotting," which chronicled a group of unemployed drug addicts in Scotland, author Irvine Welsh has been called the best storyteller in Britain. But for about 10 years now, he's lived in Chicago. We'll hear about his new book, “A Decent Ride.”

Remembering Harper Lee's Literary Legacy with Author Marja Mills

Remembering Harper Lee's Literary Legacy with Author Marja Mills

Feb. 23: Marja Mills, the Chicago-based author of "The Mockingbird Next Door" shares stories of her friendship with the late Pulitzer prize-winning author Harper Lee, who died last Friday in her hometown of Monroeville, Alabama.