It was 50 years ago that the civil rights movement shifted from the crumbling tenements of the Jim Crow south, to the cramped and segregated housing conditions of Chicago.

During the summer of 1966, a number of Chicago activists, along with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., held several marches in efforts to integrate the city's neighborhoods.

Brandis Friedman has a look back at one of those marches in particular, and how it's being remembered.

TRANSCRIPT

Brandis Friedman: The day began with a protest outside a real estate office at 63rd and Kedzie.

Dr. Martin Luther King and 700 marchers were protesting tactics, like redlining and restrictive covenants, that were used to keep blacks from integrating this white working class neighborhood.

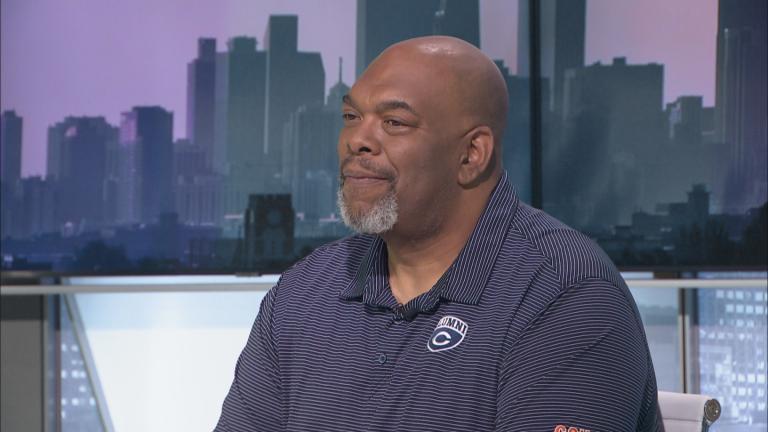

Then 24 years old, Jesse Jackson recalls the months of protesting and organizing called the Chicago Freedom Movement.

Jesse Jackson Sr.: We met very stiff community resistance. Behind walls, there's always ignorance, fear, hatred and violence. So there was this fear of black people coming west. That fear became violent.

Friedman: On Aug. 5, 1966, demonstrators marched from that real estate office to Marquette Park, where they were met by a mob of 7,000 angry whites. Sixteen-year-old Jim Caprero lived blocks away.

Jim Caprero: I saw thousands and thousands of people, mostly young white thugs. People who were angry and mean, and shouting terrible racial epithets at somebody who was beyond the policeman. Somebody connected with the taverns were bringing out crates of empty beer bottles and stacking them on the sidewalk so that the thugs in the crowd could use them as missiles to hurl over the police at the protesters.

Friedman: A rock, not a beer bottle, would strike Dr. King in the head.

He told reporters he was immune to the blow, but few would forget how Dr. King described the rest of his experience.

Martin Luther King Jr. archive: This is a terrible thing. I've been in many demonstrations all across the south. But I can say that I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I've seen in Chicago.

Friedman: At the time, King and the civil rights movement were turning their attention from the south to the north, where racism and discrimination took a different shape.

Map: Chicago Freedom Movement open-housing marches in the summer of 1966

Jackson Sr.: There was the sense that segregation in the north was quote-unquote subtle: you couldn’t “find it”; you couldn’t “detect it” like down south. We could go to Comiskey Park. We could go to Wrigley Field. You could not live west of Halsted, we could do certain things we couldn't do in the south. We could sit in public parks in the daytime. We found that the most hostile reaction–more-so than Birmingham, frankly–was Gage Park and Marquette Park. Whole communities just erupted. They were demanding to protect their property, protect their houses from feared blacks.

Friedman: Open and fair housing became the new ground zero.

Jackson Sr.: We knew that we had hit a nerve of racial segregation in housing. Of course, if you limit housing, you limit access to schools, and businesses, and capital.

Friedman: Aurie Pennick has been an open housing advocate, but was a teen in the ‘60s and joined King in the Chicago Freedom Movement. She missed this particular march and the violence that came with it.

Aurie Pennick: I can't say I was shocked by it. I was upset by it, as anyone would be … but I can't say it surprised me.

Friedman: Today, the community demographics are different.

The Marquette Park neighborhood sits in the Chicago Lawn community area. Census data shows that in 1970, four years after the march, Chicago Lawn was 98.5 percent white, and zero percent black. The median family income was $65,000 and only 4 percent of families were below poverty.

In 2010, the area is now just 3 percent white, almost 54 percent black and almost 42 percent Latino.

But as the percentage of minorities increased, the median family income declined, to barely $40,000. And 26.5 percent of families live in poverty.

The park itself is to be the home of the city’s only permanent memorial to King’s work here in Chicago. Efforts to finance and build the memorial are being led by a coalition of churches, synagogues, community groups and the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, IMAN.

Rami Nashashibi, IMAN director: I think the history of King in Chicago is sometimes not as well appreciated, or celebrated. I think it also raises for us some difficult questions about the state of the city now, as opposed to where it was 50 years ago.

Friedman: The memorial unveiling will also coincide with a march to reenact the one King led 50 years ago. At the time, he called it the first step in a thousand-mile march.

Alia Bilal, IMAN: We are retracing part of that path, not to relive any of the violence or the difficulties of that day, but I think to demonstrate how far we've come. To demonstrate what a community can look like after people who have been working, who have been striving towards creating a vision of the beloved community.

Friedman: Many communities in Chicago still suffer from segregation and concentrated poverty. Activists agree a great distance remains on King’s 1,000-mile march.

Nashashibi: We would be naive, also and irresponsible not to continue to address the ongoing sets of challenges that make the journey still an arduous one, one that perhaps, still has many more miles but, in order to look forward, we have to get hope and resilience and a sense of encouragement from where we've come.

Jackson Sr.: We've learned to survive apart; we must learn to live together. And we have worked diligently on the hard part, on the apartheid, on the walls. We must work as diligently on the bridges.

Friedman: But leaders from then and now can look to the positive changes, somewhat more diverse neighborhoods and being the adopted hometown of the country’s first black president, to see how far they’ve come in 50 years and just a few blocks.

Note: This story originally aired on “Chicago Tonight” on Aug. 4, 2016.

Follow Brandis Friedman on Twitter: @BrandisFriedman

Related stories:

Civil Rights Icon on America’s Racial Divide, Then and Now

Civil Rights Icon on America’s Racial Divide, Then and Now

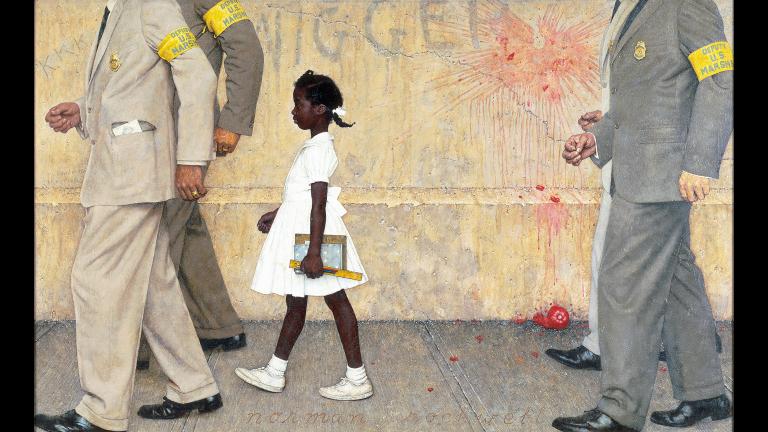

Oct. 19: Ruby Bridges became a civil rights icon at the age of 6, when she became the first African-American child to attend a previously all-white elementary school in New Orleans. She joins us in discussion.

Segregation and Racial Barriers on Chicago's South Side

Segregation and Racial Barriers on Chicago's South Side

March 23: A new book by Natalie Moore about the South Side blends personal history with investigative reporting to tell the story of a segregated city and misunderstood neighborhoods.

Report Highlights Struggles in Chicago's Segregated Communities

Report Highlights Struggles in Chicago's Segregated Communities

March 14: This year marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Great Migration, but a new report from the Chicago Urban League says many blacks still live in racially segregated and impoverished neighborhoods.