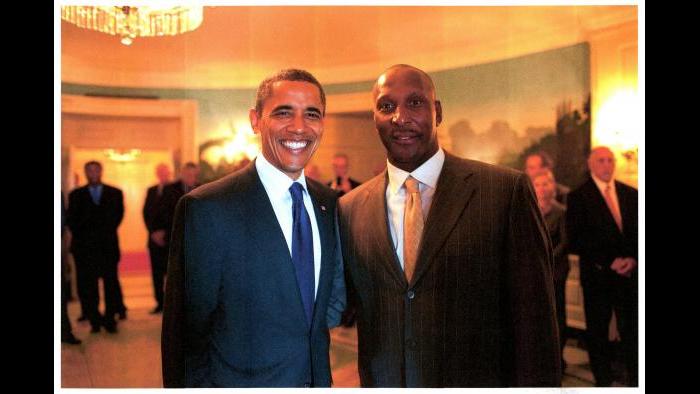

Otis Wilson was a key member of the Chicago Bears Super Bowl team in 1985.

He was a first round draft pick in 1980 for the Bears who helped the monstrous defense as an intimidating pass rusher.

In a new book, Wilson brings stories from the locker room and the sidelines. It’s called “If These Walls Could Talk: Stories from the Chicago Bears Sideline, Locker Room, and Press Box.”

Below, an excerpt from the book.

![]()

PREFACE

Otis Wilson! He really wasn’t so much a football player as he was a 240-pound missile, a king cobra with a mean streak that said in bold type, “I own you. There is no debate. Engage me on my turf and I won’t hesitate to leave your body a badass shade of purple.”

It’s hard to believe that Otis is 60 years young as he settles his razor- sharp frame into a booth at Chicago’s historic East Bank Club on an October Friday in 2016. “O,” as he’s known, is still winding down from his normal 90-minute workout, a stress test he says he requires daily to “avoid feeling vulnerable.”

It’s hard to believe that Otis is 60 years young as he settles his razor- sharp frame into a booth at Chicago’s historic East Bank Club on an October Friday in 2016. “O,” as he’s known, is still winding down from his normal 90-minute workout, a stress test he says he requires daily to “avoid feeling vulnerable.”

Vulnerable? Hardly.

The kid from the rugged streets of the Brownsville district in Brooklyn, New York, is blessed with remarkably cooperative genetics. While most aging NFL players wage never-ending battles with midsections drooping over trousers, Wilson claims that he weighs 230—down 10 pounds from the days he was in shoulder pads. I’d bet the rent his body fat does not exceed 10 percent. Really, he is a chiseled slab of muscle and bone.

His temples and stylishly trimmed beard have begun to sprout flecks of gray, the only indication that Father Time is beginning to look in his direction.

Yes, Otis Wilson remains larger than life. As he wolfs down egg whites with spinach, numerous passersby can’t resist a glance at one of the most gifted players in Bears’ history. Some of the gawkers never saw Wilson play, but they’ve heard the stories.

Fathers and grandfathers have related the tales of the agile and physically punishing Wilson, the 1985 Super Bowl champion Bears, and the historic 46 defense.

Some may argue that certain clubs have had better defenses over the years than the ’85 Bears, but don’t let anybody ever tell you there was a “D” that brought intimidation and dominance the way Otis and his partners in crime brought it to football Sundays.

Middle linebacker Mike Singletary was the run-stopping force in the middle. Singletary’s facial expressions were so dark, so foreboding, that CBS TV made his gosh-darn eyes—his freakin’ bulging eyes for heaven’s sake—an ongoing promo for games involving the Bears. Wilber Marshall played with an intensity that, in polite terms, made you wonder if the kid out of small-town Florida was psychotic.

Wilson, blessed with a Hollywood smile, was the freelancing mechanic whose first-step quickness and remarkable football intelligence simply made 10 other defensive teammates look just that much better.

Over the course of NFL history, dating back to the Canton Bulldogs and the Portsmouth Spartans, the only trio of ’backers that merit a comparison to Wilson, Samurai Mike, and Bad Wilber would be the New York Giants talented grouping of Lawrence Taylor, Carl Banks, and the soft-spoken but manically tough Hall of Famer Harry Carson.

Yes, Pittsburgh’s steroid driven, Steel Curtain–era bullies Jack Lambert, Jack Ham, and Andy Russell were special, but they didn’t play on the same level of the three Bears. End of issue. Arguments will not be accepted.

But let’s go back to Brownsville, an area heavy on crime, drugs, and stolen guns, a ’hood that wasn’t as bloody violent as Compton but was about as forlorn in its own way as Chicago’s notorious Lawndale district. Before World War II, the ’Ville was largely populated by Jewish people, many of them Hasidic. But as the ’50s rolled into the ’60s the area became a conclave for black New Yorkers.

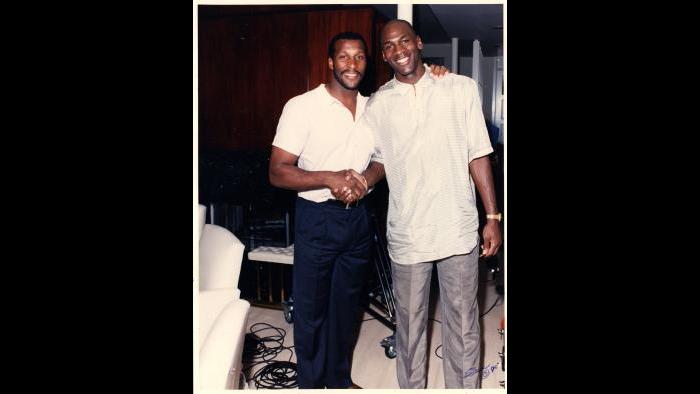

Wilson, a child of the projects, hung out with future NBA round- ballers like Lloyd “World B.” Free and Bernard King, former light heavy- weight boxing champion Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, and in later years, ex-heavyweight champ Riddick Bowe.

Hell, Otis knew Mike Tyson when the eventual “Baddest Man on the Planet” was just a young punk looking to shake down local bode- gas or grab a wallet off some square who’d happen to wander down the wrong street—his street.

Otis was never intrigued by the gangster lifestyle, and truth be known the gangs had no interest in him. As is the case in so many blighted urban areas, jocks were held in high esteem. They were the local rock stars, looked upon as guys to be admired and fellows who had the chance to escape the cruelty of the urban dungeon.

Mind you, Otis’s mom and grandma saw to it that Big O and his siblings always had plenty of food on the table and clean clothes to wear. There wasn’t extra money for Broadway theater tickets, but Wilson never lacked for the necessities. Maxine Wilson, O’s mom, stressed class and an uncommon level of decency.

Otis knew by his senior year that there was more to life than the asphalt in Brooklyn, or the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge linking his home base to the glitter, glamour, and, lest we forget, the Studio 54 decadence of Manhattan.

Major colleges from coast to coast wanted the unique specimen from Thomas Jefferson High School, the kid who’d been groomed by local legend Moe Finkelstein. Ohio State’s Woody Hayes flew in to make his pitch, as did Michigan boss Bo Schembechler and Pitt’s Johnny Majors.

So, was Wilson floored by the attention of gridiron royalty? He will tell you that in truth he had no idea who the hell those guys were.

Such was life in the ’hood, where knowledge wasn’t measured by states, it was measured by playgrounds.

Eventually after one very sour year at Syracuse, Otis gravitated to Louisville, a basketball school where Denny Crum and Darrell “Dr. Dunkenstein” Griffith were considered much higher priorities on the Cardinals’ food chain than guys belting tackling dummies.

A side note: if you let Otis bend your ear for more than 90 seconds, he’ll have you convinced, lock, stock, and Nikes, that he could easily have been an NBA basketball player. In the ’80s, his dimensions screamed “small” but muscular power forward with razor-blade elbows and a soft midrange jump shot. The shot was cool. The elbows were statements.

A superb senior year at Louisville moved the Sporting News to honor Otis as a first-team All-American. The accolade was hardly required. Veteran Bears’ scout Jim Parmer knew Wilson was a physical freak. As such Jim Finks, the taciturn but remarkably engaging, and chain-smoking, general manager of the Bears, used a first-round pick in 1980 to bring Wilson to Soldier Field.

Suddenly, the kid who wandered from the ’Ville was learning the ropes at the Bears’ Halas Hall football compound in the pricey north Chicago suburb of Lake Forest.

While the Brooklyn that Otis knew had all too often featured empty syringes tossed off curbs and winos begging quarters, Lake Forest always seemed to burst with Republican money, inherited wealth, and, perhaps, a few lawyers on the take.

Stop! There is so much to cover regarding “Mama’s Boy Otis.” Hop on the bus as we make our way through a gridiron life that brings a special meaning to the time-honored phrase “The American Dream.”

We need to bring you up to speed about the level of disgust Wilson had for Mike Ditka. The Big O and Ditka were never especially chummy. The fact is Otis once got in Ditka’s face and barked, “I’m a man just like you are. I’m not gonna kiss your ass.”

We need to go over the reverence John Madden had for “O” and just why the legendary “Super Bowl Shuffle” really should have been titled, “Otis and Willie Gault prove with clarity that white guys can’t dance under any circumstances.”

Did we mention Dan Hampton and Mongo McMichael, Gary Fencik, Dave Duerson, Hall of Fame defensive end Richard Dent, or the Fridge? Trust me we’ll get there.

Meanwhile, Maxine Wilson, you raised one helluva kid and one special man. Your son, never blinded by the uncertainty of the neighbor- hood, has lived by your words about admitting when you’re wrong and for God’s sake making things right if you think you screwed up.

This is for a character’s character, a man’s man—Otis Wilson. This is his story with no punches pulled and no holds barred. This is for a man whose friendship I’ve relished over the past 37 years.

Big O, let’s show ’em how to dance. Wilson style!

—Chet Coppock

This excerpt from If These Walls Could Talk: Chicago Bears by Otis Wilson with Chet Coppock is printed with the permission of Triumph Books. For more information and to order a copy, please visit www.triumphbooks.com/WallsBears.

Related stories:

Suburban High School Football in Downward Spiral, Analysis Shows

Suburban High School Football in Downward Spiral, Analysis Shows

Oct. 26: Youth football seems to be taking a hit. We speak with a Daily Herald investigative reporter about steep declines in high school football participation.

Chicago Bears’ Luck Runs Out: Coin Toss Winning Streak Ends at 14

Chicago Bears’ Luck Runs Out: Coin Toss Winning Streak Ends at 14

Oct. 9: You could say it was flipping amazing while it lasted, but at Soldier Field on Monday night, the Bears coin toss winning streak ended at 14 in a row.

NFL Players Kneel, Lock Arms in Unity During National Anthem

NFL Players Kneel, Lock Arms in Unity During National Anthem

Sept. 25: If you tuned in to watch any NFL game Sunday, you saw nearly all the football players in the league—and even some owners—join in a silent protest during the national anthem. Sports columnist Rick Telander weighs in on the controversy