Why does the Metra Union Pacific North Line run on the left? Who is the statue on 25th and King Drive? Plus, a Chicago landmark is undergoing a renaissance as a luxurious hotel on Michigan Avenue. We take a peek under the dust in tonight's Ask Geoffrey.

![]()

I have always wondered why the Metra Union Pacific North Line runs on the left side, unlike other Metra lines. What's up with that?

– John Kerr, Evanston

The Union Pacific North Line, which old folks like me remember as the Chicago and Northwestern, runs the way cars do in England, on the left side of the street, or in this case on the left hand track where there are two tracks. This is called “left-hand running” in railroad jargon.

In fact, the other two Metra lines that were formerly part of the Chicago and Northwestern also have left-hand running, the Union Pacific Northwest Line and the Union Pacific West Line.

One urban myth that Metra and most experts rule out is that the line had a large number of British investors, so the trains were operated the British way. In fact there were no British investors.

The most likely explanation goes back to the first of these three lines to be built, which is now the Union Pacific West Line. It opened in 1848 as the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad.

The depots were put on the north side of the track, so when a second track was added, instead of tearing down the stations, they just put that track on the south side.

Station houses were needed more for inbound passengers, who might show up early and have to wait, so the inbound track was the one on the left side.

When C&NW bought the other two lines, UP NW and UP N, they continued this practice. One benefit of this was that they could shift crews from one line to another without possibly hazardous confusion.

All of the other Metra lines run right-handed, as does the ‘L’ and most railroads in the U.S. Switching direction of tracks at this point would involve millions of dollars to change all of the signaling and building new station houses or moving existing ones, many of which are historic structures.

I would like to know about the statue on 25th and King Drive in Chicago. Do you know the name of the man the statue represents?

– Elaine Roberts, Chatham

He doesn’t represent a single person, but rather an important part of African American history.

This is called the Monument to the Great Northern Migration. It commemorates the hundreds of thousands of African-Americans who moved to Chicago from the Deep South in the 20th Century.

The bronze figure is wearing a suit made from worn shoe soles, symbolizing the long, difficult journey.

A City of Chicago description of the statue says: “The traveler’s hand is raised in salutation to his new home. In his other hand he carries a worn suitcase symbolic of his journey, dreams and talents. The bollards surrounding the monument are also suitcases that are textured with a pattern derived from the tin ceilings of the era. The figure is oriented to the north, symbolizing the traveler’s destination.”

The sculpture is the work of Alison Saar, who was born in 1956. Sometimes when kids announce they want to pursue a career in art, their parents are not exactly thrilled. However, Allison Saar’s parents were important artists themselves, and they inspired her to become a sculptor.

I recently started a construction job at 12 South Michigan, the old Chicago Athletic Association. What can you tell me about the club’s history?

– Fred Hodgers, Mokena

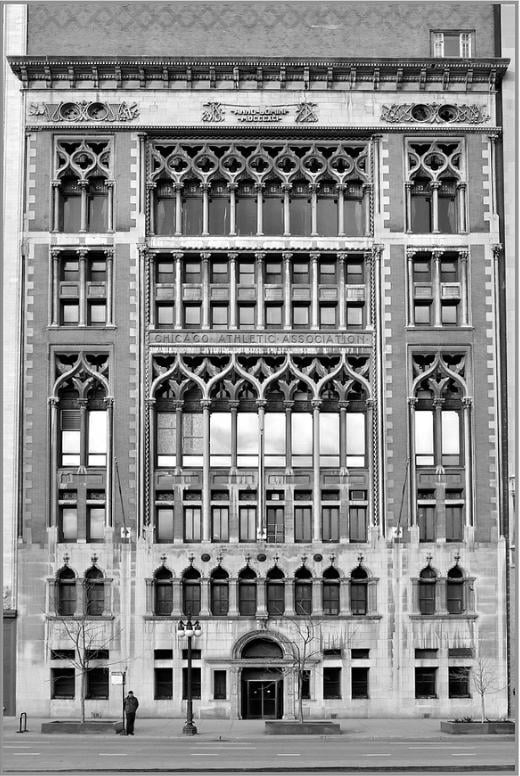

Chicago Athletic Association Facade

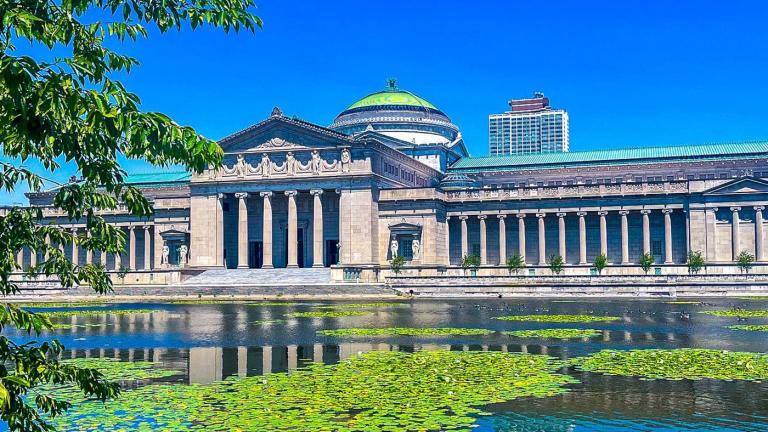

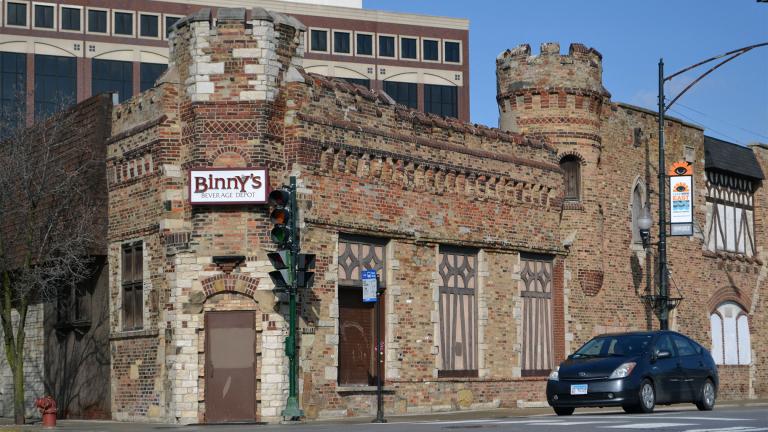

This former private club, opened in 1893, sits on Michigan Avenue directly across from Millennium Park. It closed in 2007 and is currently being converted into a hotel.

Chicago Athletic Association Facade

This former private club, opened in 1893, sits on Michigan Avenue directly across from Millennium Park. It closed in 2007 and is currently being converted into a hotel.

The building was created in part to impress the millions of people who would visit Chicago that year for the World’s Fair. The design of the club’s façade was fashioned in opulent Venetian Gothic style, modeled after Doges Palace in Venice Italy, which was built in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Club’s founders were elite Chicagoans like Marshall Field, Cyrus McCormick, and A. G. Spalding, who wanted to create a new club focused on athletics.

The hotel developer allowed our cameras inside, and you can see that much of the opulent interior remains and is being saved. The club had bowling alleys, rifle ranges, tennis courts, billiard rooms, a Turkish bath and swimming pool, and a gymnasium.

The architect was club member and wealthy former New Englander Henry Ives Cobb.

At just 34 years old, Cobb was already famous for his high-profile designs of the Newberry Library, the old Chicago Historical Society (Excalibur), and the University of Chicago’s Gothic quadrangles. He later designed the Federal Building with a dome larger than the U.S. Capitol, where Mies’s Federal Center is now.

From the beginning, women were allowed into this men-only club to witness sporting exhibitions – and to view muscle.

In the early days, the club fielded amateur teams that competed against clubs in other cities and often held exhibition games as warmups to college games. Team members were offered free membership in the club.

The club’s logo looks a lot like the familiar Chicago Cubs emblem, and in fact it is said that club member William Wrigley adopted the CAA logo for the team.

At its peak the club had 3,000 members but by the end that had dwindled to around 500.

The new Chicago Athletic Hotel opened in 2015. It has 240 rooms, a rooftop bar, and restaurant with spectacular views on Millennium Park.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.