Geoffrey Baer answers viewer questions about a missing Mahler brother, Chicago’s hippie haven, and Evanston’s Cary Grant connection in this week’s edition of Ask Geoffrey.

I read that RKO Studios had replicas of the house in the 1948 movie “Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House” built across the country. Is one in Chicago?

David Buckley, Brookfield

Not in Chicago, but very close, in Evanston. And it still stands today. “Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House” was a 1948 RKO Studios comedy starring Cary Grant as the Mr. Blandings of the title and Myrna Loy as his wife.

The story followed Mr. Blandings as he and his family left a cramped Manhattan apartment for the rolling country of Connecticut, where they endeavored to have their dream house built General Electric Dream House and, of course, misadventures and hijinks ensued.

RKO did actually build a real house for the film in the nearby Malibu Hills, Calif. Legendary producer David O. Selznick also cooked up the idea of a massive promotion for the film in conjunction with General Electric Corporation (GE). Selznick had the blueprints for the house, a four bedroom colonial, sent to builders for free across the country.

The plan was for a hundred homes to be constructed. And 73 dream houses were actually built, furnished and raffled off from California to Massachusetts, including one in northwest Evanston. Most of the dream houses were equipped with state of the art GE appliances, like an automatic washer and dryer, dishwasher and garbage disposal, as well as a garage door opener.

RKO and GE took full advantage of the stunt, hosting open houses, publicity events, and bringing newspaper columnists in to run stories about every aspect of the homes, from the newfangled appliances to the décor.

The current owners of the Evanston house allowed us to come and film their home, which they say is incredibly sturdy.

Since it was the cold war era, they said the basement is essentially a bomb shelter. They are the third owners of the house and have maintained much of the original design, from the gingerbread exterior trim to the little balcony in the back.

And just like the house in the movie, this one had its share of problems as well. Among them, the owners told us about a time when they found that the lights that were on in the house couldn’t be turned off -- and the lights that were off couldn’t be turned on.

They called in an electrician to find that the house was wired for extremely low voltage which was apparently one of the futuristic aspects of the design -- he said the wire was like the wire you’d use in a toy train – and they wound up rewiring everything.

By the way, if you want to build your own dream house, you can still find the blueprints on the Internet.

I read an article about the brother of the composer Gustav Mahler that said he lived in Lincoln Park. Can you tell us more about his life in Chicago?

Michael Arsers, West Rogers Park

Yes, Gustav Mahler’s younger brother Alois lived in Chicago for the last 20 years of his life but very little is known about him. No photos exist that we could locate.

Big brother Gustav, of course, is the great composer born in Bohemia in 1860 and raised in Austria. He was one of 14 children. Only eight survived to adulthood, including Alois, who was born in 1867.

Sometime after his parents died, Alois changed his name to Hans Christian. This was an interesting choice, given that the Mahlers were of Jewish heritage. In 1910, Hans immigrated to America and settled in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago. He worked representing Heller’s Candies of Vienna, makers of the Wiener Zuckerl, a fruit-filled hard candy still available today. Later he became a baker and his occupation was listed as a real estate broker on his death certificate.

Through much of his time in Chicago, up until he died, Hans lived in this apartment in Lincoln Park at 2254 North Fremont. Records show he had a wife named Margaret, most likely his second marriage after his first wife, Bohumila, died, although it is not known if he had any children. Hans Christian Mahler died of stomach cancer in Chicago on April 1, 1931 at age 63 in Cook County Hospital.

His remains were cremated at Graceland Cemetery, but we don’t know what became of his ashes. Some writings about Alois have characterized him  as something of a black sheep in the Mahler clan. In family letters, he was described as dishonest and unreliable.

as something of a black sheep in the Mahler clan. In family letters, he was described as dishonest and unreliable.

One researcher called him a “Baron Munchhausen type pathological liar” and a “lifelong embarrassment to his brother.”

But Susan Filler, the only scholar who has really researched Alois specifically, could not find any evidence that those tendencies continued during his more than 20 years living in Chicago.

Despite his siblings’ condemnation, according to Filler, existing records seem to indicate that the Hans Mahler of Chicago was hardly a ne’er do well, but a pretty ordinary guy who just happened to be the brother of a musical genius.

How did it come about that the area around North Avenue and Wells Street is called Old Town?

Larry Zgoda, St. Ben’s

While it is an old neighborhood, Old Town didn’t officially become Old Town until the 1940s.

During World War II, the triangular area bordered by North Avenue, Clark Street, and Ogden Avenue, which ran up to Lincoln Park until the 1960s, was designated a “neighborhood defense unit” by the Chicago Civil Defense Corps. After the war was over, the neighbors maintained the spirit of their community by sponsoring popular annual art fairs they called the “Old Town Holiday."

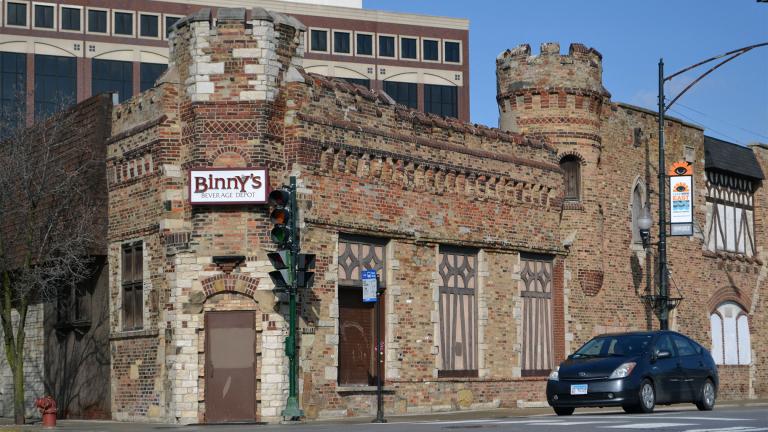

The “Old Town” name got used again in 1948 when the same area residents formed the Old Town Triangle Association. In an age when people were fleeing the city for the suburbs and then urban renewal was leveling nearby areas, local small business owners dug in and Old Town became an amalgam of bohemian artists, funky, kitschy tourist traps and later a hippie enclave.

The big attraction back then was Piper’s Alley. It’s a mall today, but when it opened in 1965 it was a real alleyway. It was named after the business which preceded it, Piper’s Bakery. I still remember as a kid entering the narrow, brick alley under a giant tiffany lamp. Piper’s Alley was lit by old-fashioned lampposts. It was home to the famed Second City Theater, head shops, a general store, penny candy shop, a candle store, a funky clothing emporium and a pizza parlor.

The big attraction back then was Piper’s Alley. It’s a mall today, but when it opened in 1965 it was a real alleyway. It was named after the business which preceded it, Piper’s Bakery. I still remember as a kid entering the narrow, brick alley under a giant tiffany lamp. Piper’s Alley was lit by old-fashioned lampposts. It was home to the famed Second City Theater, head shops, a general store, penny candy shop, a candle store, a funky clothing emporium and a pizza parlor.

Wells Street was the main drag. You could get a burger and a beer at Chances R, where you were invited to throw peanut shells on the floor. There was a Wax Museum and Ripley’s Believe it or Not Museum and later peep shows. The original Crate and Barrel store was there. Glasses and dishware were displayed in real wooden barrels filled with straw.

And, of course, folk music clubs like the Earl of Old Town where Steve Goodman and John Prine performed and the Old Town School of Folk Music.

And, of course, folk music clubs like the Earl of Old Town where Steve Goodman and John Prine performed and the Old Town School of Folk Music.

Before the neighborhood got its “Old Town” name in 1946, it was called North Town, since it was north of North Avenue, which was the city’s original northern boundary. And going back even further in time, according to some accounts, the area was first known as Cabbage Patch because the German immigrants that settled there in the late 1800s and early 1900s grew potatoes, celery, and cabbages on the marshy land. These days, the neighborhood is a thriving mix of residences, restaurants and retail.