In this edition of Ask Geoffrey, viewers ask our local history expert Geoffrey Baer about the Marshall Field’s clock, a World War II memorial in Lincoln Park and the Chicago Federal Building’s dome.

My mother and I have an inquiry about the famous Marshall Field's clock. Who designed and made it, where and when, and what is it made out of?

–Nick S., Chicago

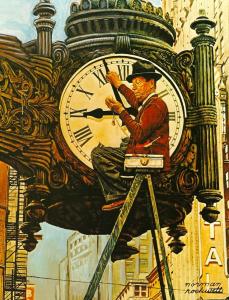

"The Clock Mender"

The viewer is, of course, referring to the beloved clocks on the former Marshall Field’s State Street store, now Macy’s, at the corners of State and Washington and State and Randolph. According to the folks at Macy’s, the clocks were designed by Pierce Anderson and Ernest Graham for the store’s architect D.H. Burnham. The clock at Washington and State was the first to be built in 1897.

"The Clock Mender"

The viewer is, of course, referring to the beloved clocks on the former Marshall Field’s State Street store, now Macy’s, at the corners of State and Washington and State and Randolph. According to the folks at Macy’s, the clocks were designed by Pierce Anderson and Ernest Graham for the store’s architect D.H. Burnham. The clock at Washington and State was the first to be built in 1897.

The second clock at Randolph and State was added in 1904. According to Federated Department Stores, both clocks are made of bronze and weigh over 7 tons each. The hands are made of wood. The clock’s faces measure 46 inches’ across, the minute hands are 27 inches long and the hour hands are 20.5 inches. The clock faces just received a paint job to revive the faded numbers on the dials. Until 2009, the clocks were controlled by a master clock inside the building, but since then they have been wired to a GPS system that synchronizes them four times daily.

Macy’s representative Andrea Schwartz said that Marshall Field noticed people using the corners of State and Washington and State and Randolph to meet, so he had the clocks created and erected as a symbol and a meeting place for his store. It wasn’t long before “meet me under the clock” became a common plan for shopping Chicagoans.

In 1945, the clock at Randolph and State was immortalized as a Chicago symbol when Norman Rockwell painted it for the cover of the Nov. 3 Saturday Evening Post. In 2006, when Federated Department Stores prepared to take over the store from Target Corporation, they discovered that the painting of The Clock Mender on display at the store was actually a reproduction. The Target Corporation said they had stored the original painting because they planned to donate it the Chicago History Museum, which they did in 2006. The painting is now permanently on display at the CHM.

There is a World War II killed in action memorial marker to George Estes at Fullerton and Cleveland. Who was he, who erected the memorial, and are there other markers like it around the city?

–Georgia Nester and Greg Gottstein, Lincoln Park

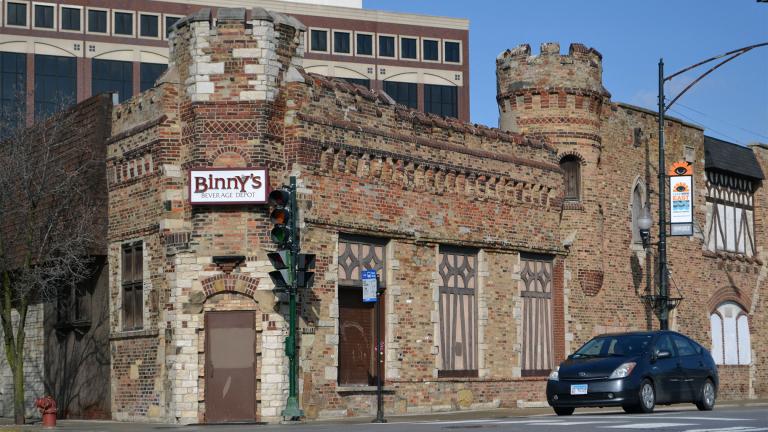

The memorial to George Estes at Fullerton and Cleveland is one of a vanishing few remaining around Chicago. George Estes was a Seaman Second Class in the Navy during World War II. According to his obituary, he was killed in action in the South Pacific in October 1944 and was buried at sea. He had lived with his family a few blocks away at 2046 N. Orleans. There’s another memorial like Estes two blocks west at Fullerton and Orchard, this one for Richard Fassl, a bombardier and fellow Lincoln Park resident who was killed in action over England. Today, Fassl’s and Estes’ memorials are lovingly maintained by the Mid-North Neighborhood Association.

There were many of these types of memorials erected throughout Chicago during and after World War II by neighborhood residents, clubs, or even nearby businesses to honor those who served. Many were like George Estes’ memorial—simply a post bearing a plaque with the name of the serviceman, often on a street corner. Others, called Honor Rolls, were erected during the war and listed the names of men and women from the neighborhood serving in the war. Some were embellished with flagpoles and Vs for victory.

Unfortunately, these days the memorials are few and far between. On some of the post-and-plaque type of memorials, attachments deteriorated and the plaques fell off. Sometimes you’ll come across an empty pole, like one found in Englewood. Many more were removed by the city and developers as neighborhoods changed and street improvements were made.

But a handful can still be found around the city, like this memorial flagpole and small garden in Bridgeport near 30th and Canal that is beautifully maintained by neighborhood residents. Remnants of other memorials still linger as well, as you’ll see in the video below.

In Roscoe Village at Barry and Leavitt, there’s a flagpole in a star-shaped stand that was once part of a neighborhood memorial, and on the southwest corner of Grand and Artesian in the Ukrainian Village neighborhood, a V remains in the sidewalk where a flagpole used to stand.

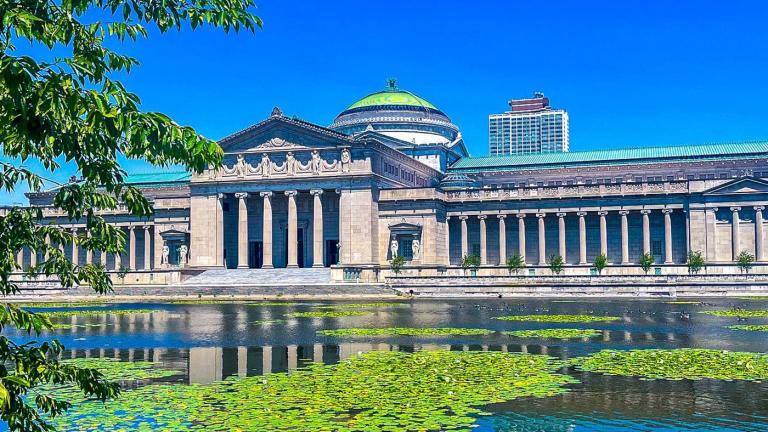

I was told the old Chicago Federal Building on Jackson and Dearborn had a dome comparable to that of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. and that a hidden image of the face of Uncle Sam could be seen in the afternoon on a sunny day. Is this true?

–Tom Nichol, Downers Grove

The Federal Building’s dome was actually larger than the U.S. Capitol’s dome! And as for Uncle Sam, the best answer we can give is “maybe.”

The massive, granite-clad Chicago Federal Building was designed by Henry Ives Cobb. It stood on the site of today’s Federal Center on the block bounded by Dearborn, Adams, Clark and Jackson. It was completed in 1905 and dedicated as the “Post Office, Customs House and Sub-Treasury.” Al Capone was convicted of tax evasion in one of its courtrooms.

According to the Historic American Buildings Survey report, the grand edifice was topped with a gilded glass-tile dome 100 feet wide that reached 297 feet into the sky, outclassing the U.S. Capitol dome in both dimensions.

So what about that Uncle Sam story? The very reliable Historic American Buildings Survey’s report on the Chicago Federal Building states that the shadows and outline of the dome create an image of Uncle Sam at a certain time of the afternoon when viewed from Adams and Dearborn – but that claim seems a little dubious. We were unable to turn up any photo evidence of the image, for one thing. It’s also a little hard to imagine what they could’ve seen. The modern-day image of Uncle Sam wasn’t around until about a decade after the Federal Building was completed.

Despite the efforts of preservationists, by 1960 it was determined that the building had become too small. It fell to the wrecking ball in 1965 and was replaced by Mies van der Rohe’s Modernist Kluczynski Federal Building and an adjacent post office. Two of its stately columns were saved and now grace the entrance to the Cancer Survivors’ Garden on the northern end of Grant Park.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.