A new study led by the University of Chicago shows people who didn’t get a good night’s sleep could not resist the temptation of a midday snack. (Credit traska / Flickr)

A new study led by the University of Chicago shows people who didn’t get a good night’s sleep could not resist the temptation of a midday snack. (Credit traska / Flickr)

That afternoon slump that has you craving a Snickers bar could be due to lack of sleep.

A new study led by the University of Chicago shows that skimping on sleep may make it more difficult to resist the temptation of a midday snack.

“People need to think of adequate sleep as an important aspect of maintaining good health," said Erin Hanlon, Ph.D., lead author of the study and a research associate in endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Chicago.

“There’s been some evidence from both laboratory and epidemiologic studies that consistently associate insufficient sleep with increased risk of obesity," she said. "Most recently, studies have shown short sleep duration associated with actual consumption of snacks and high-energy, high-fat foods.”

Foods like the often irresistible stuff packed into office vending machines or shared at the company potluck that are typically high in sugar, fat and salt.

The U. of C.'s new study focused on reward-driven eating by comparing the effect that normal sleep and restricted sleep have on endocannabinoids, lipids that bind to the same receptors as THC, the active ingredient of marijuana.

The endocannabinoid system is involved in many functions including stress, immune response, feeding and reward, Hanlon said. And activation of the endocannabinoid receptors promotes hedonic eating – eating for reward or pleasure.

In other works, Hanlon said, “I’m not eating it for the energy needs. I’m eating it because that cookie tastes good.”

The study states that "under normal sleep conditions, blood levels of the most abundant endocannabinoid increase from mid-sleep to early afternoon. After sleep restriction, this increase in endocannabinoid level is amplified, coinciding with greater desire for palatable food.”

How the study worked

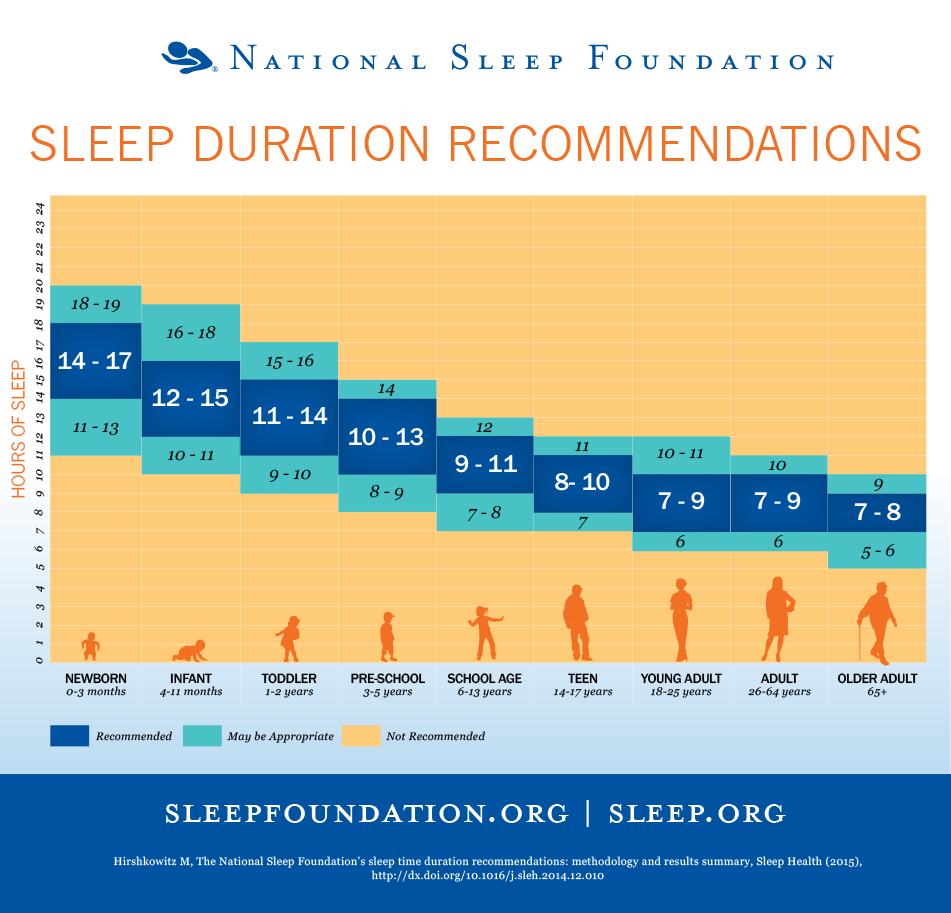

Fourteen participants — 11 men and three women — all healthy, lean individuals in their 20s participated in the study at the University of Chicago's Clinical Research Center. Hanlon says participants were screened to ensure their sleeping habits included 7 to 9 hours of sleep a night, between the hours of 11 p.m. and 8 a.m. In other words, these were generally sound sleepers, not tossing-and-turning insomniacs.

Each session lasted four consecutive days, during which participants were monitored, housed in private rooms and limited to sedentary activities. In one session, participants spent 8.5 hours in bed (averaging 7.5 hours of sleep); in the so-called sleep-restriction session, they spent 4.5 hours in bed (averaging just 4.2 hours of sleep).

“They were always monitored to make sure they were not napping, and then went to bed when they should or at least the lights were out and they weren’t on the phone. And in the sleep restriction [session they were monitored] to make sure they weren’t falling asleep,” Hanlon said. “While they were with us they did a bunch of questionnaires about hunger and appetite.”

After acclimating to sleeping in the center, participants ate identical meals three times a day, at 9 a.m., 2 p.m., and 7 p.m. on the third day of each session.

“We do it so the blood levels weren’t based on food preference or how much [participants] ate," Hanlon explained. “[The meal is] isocaloric, meaning those three meals equal the amount of energy needed for a 24-hour day, so we’re not overfeeding you and we’re not underfeeding. There are no snacks at this time.”

During this time researchers measured participants’ leptin and ghrelin levels, which are hormones that modulate satiety and appetite, respectively. Researchers also measured participants’ endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) levels.

The study revealed that following a normal night’s sleep the 2-AG levels were low in the morning, peaked in the early afternoon and then decreased. After restricted sleep, the 2-AG levels rose 33 percent higher than levels observed after normal sleep; they also peaked approximately 90 minutes later and remained elevated until about 9 p.m. After restricted sleep, participants reported higher levels of hunger and a greater desire to eat.

“When people had alterations in those hormones favoring food intake, people reported they were hungry and had a stronger appetite,” Hanlon said. “They had the greatest ratings for high carbs and high-fat foods.”

After a fourth night, participants in each session were allowed access to a buffet that was tailored to their food preferences and included both healthy and unhealthy fare at meal times (lunch was served at 3 p.m. and dinner was served at 7:30 p.m.).

“The buffets always provided well in excess of what any person could eat. So we wouldn’t be left wondering if that person would’ve eaten more if more food had been available,” Hanlon said. “What’s particularly interesting about this study, at least in my estimation, is when we gave these individuals these buffets, whether they had 8.5 or 4.5 hours of sleep, at their first meal they ate 2,000 calories. … It’s hard to resist: there’s all of this cooked food in front of you and you’re told to eat as much or as little as you want in one hour. People will overeat regardless.”

In addition to buffet-style meals, participants had the opportunity to snack between meals. Again, the snacks provided were tailored to each participant’s preferences and included both healthy and unhealthy fare.

“There were healthy snacks available, but our study focused on what was actually consumed,” which was junk food, Hanlon said.

Hanlon said that even after a high-calorie buffet lunch, participants who were in the sleep-restricted phase of the study would immediately consume another 1,000 calories in snacks. Those in the normal sleep group ate only 600 calories in snacks, but as Hanlon points out, when those in this phase of the study were sleep deprived, "they even further overate on the snacks."

Despite consuming 3,000 calories (or close to that) in roughly five hours, participants consumed another 1,000 calories at dinner regardless of hours slept.

“You’d think they’d compensate for that at dinner, but they don’t,” Hanlon said. “They eat the same amount at dinner despite the 1,000 calorie snack in between.”

The sleep-restricted participants also chose foods that provided 50 percent more calories, including twice as much fat, as compared to the normal sleep phase.

“The things we’re starting to realize and the message is starting to get out there that short sleep and sleep deficiency are associated with deleterious outcomes and increased feeding,” Hanlon said.

How much sleep is enough?

The short answer: it varies.

“Sleep is very individualized,” Hanlon said. “The National Sleep Foundation breaks down sleep need by age. Adults right now lay in the range of 7-9 hours. One adult might have a need of 9 hours and someone else may be fine with 7 hours.”

Have a hard time catching Z’s?

“We do suggest — we being the sleep community— that you minimize your exposure to phones, tablets, TVs and computers before going to bed,” Hanlon said. “Light emitted from those devices can alter sleep schedules.”

Listed below are healthy sleep tips from the National Sleep Foundation:

- Stick to a sleep schedule, even on weekends.

- Practice a relaxing bedtime ritual.

- Exercise daily.

- Evaluate your bedroom to ensure ideal temperature, sound and light.

- Sleep on a comfortable mattress and pillows.

- Beware of hidden sleep stealers, like alcohol and caffeine.

- Turn off electronics before bed.

Follow Kristen Thometz on Twitter: @kristenthometz

Related stories from 'Chicago Tonight'

First Zika Case Confirmed in Chicago

First Zika Case Confirmed in Chicago

Feb. 29: The city on Monday morning confirmed the first case of Zika virus. The patient, who was identified as a woman in her 30s, visited Presence Saint Joseph Hospital after returning from a trip to Columbia with symptoms consistent with the virus.

Study: Pharmacies that Produce Compounded Drugs in Illinois Not Tracked

Study: Pharmacies that Produce Compounded Drugs in Illinois Not Tracked

Feb. 26: The state of Illinois doesn’t track the number of pharmacies that mix, combine or alter the ingredients of a drug or require those that perform sterile compounding to report serious adverse events, according to a new report by Pew Charitable Trusts.