Photographer Kenneth Josephson is not the retiring type. He's been creating innovative pictures around the world since his career began in 1958. Though he did retire from the School of the Art Institute where he taught for 37 years, Josephson remains in search of his next great photo.

TRANSCRIPT

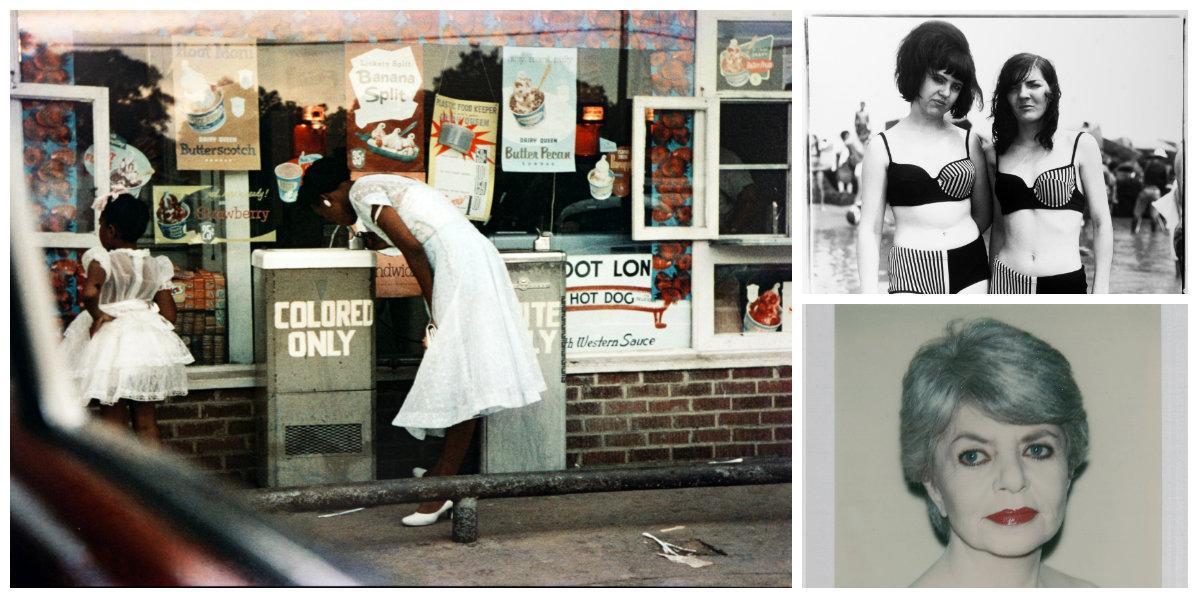

Phil Ponce: From an icy road in Stockholm, Sweden, to Chicago’s Loop in the daytime and at night, Kenneth Josephson’s body of work is defined by a series of innovations – such as revealing the presence of the person behind the camera and by the use of multiple images in one picture. Creative deviations like these established Kenneth Josephson as a photographer with an artistic eye.

Lynne Warren, Museum of Contemporary Photography: I have always felt like he’s a really important figure, not only in photography but in contemporary art. As a conceptual photographer, he really was one of the first as far as doing what are out and out conceptual photographs. Having an idea of what the image would be, how to frame it, how to print it, how to present it, and not merely going out into the world randomly shooting and then looking at the products of the proof sheet and going, ‘Oh well that’s a good image. That one kind of captures something.’ It’s a process of deliberately thinking about what you’re going to go out and shoot.

Ponce: Conceptual photography has been described as making a photograph rather than taking one.

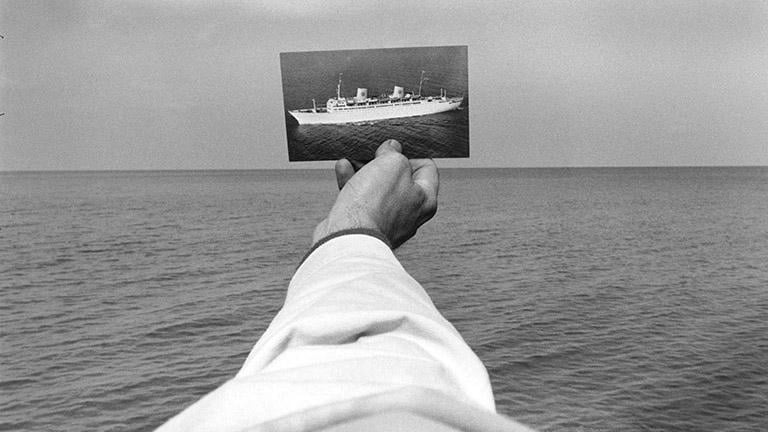

Kenneth Josephson: After teaching in Sweden for a year, I decided to take a boat, a liner back to New York.

New York State, 1970

New York State, 1970

Ponce: Josephson spoke with us about his use of humor, his technique and his inspiration.

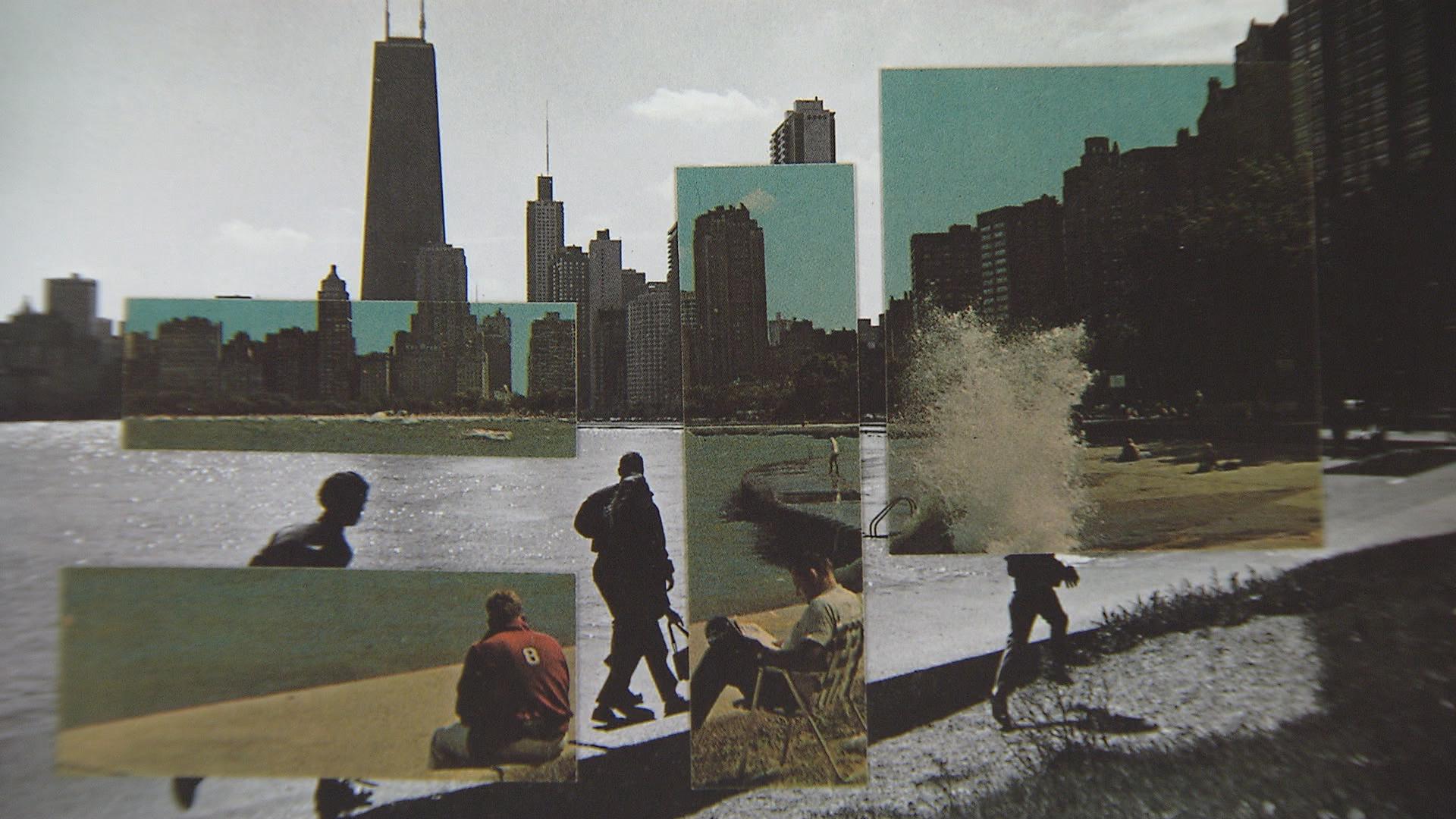

Josephson: I wanted to choose something that had a lot of possibilities, and so I chose to experiment with multiplicity, and I made certain decisions so I would be guided, so all the images would be done within the camera on the same piece of film.

Ponce: Kenneth Josephson studied at Chicago’s Institute of Design with esteemed photographers Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, who encouraged experimentation.

Josephson: When I went to the Institute of Design, there was so much freedom for you to do whatever you feel is going to be successful. If it works, in other words, that it’s okay. Aaron Siskind would talk about a photograph on paper and he’d say this isn’t reality, it’s a photographic reality, and it’s a piece of paper that can be folded or torn or whatever, and so I started thinking of the photograph as an object because of what he was telling us.

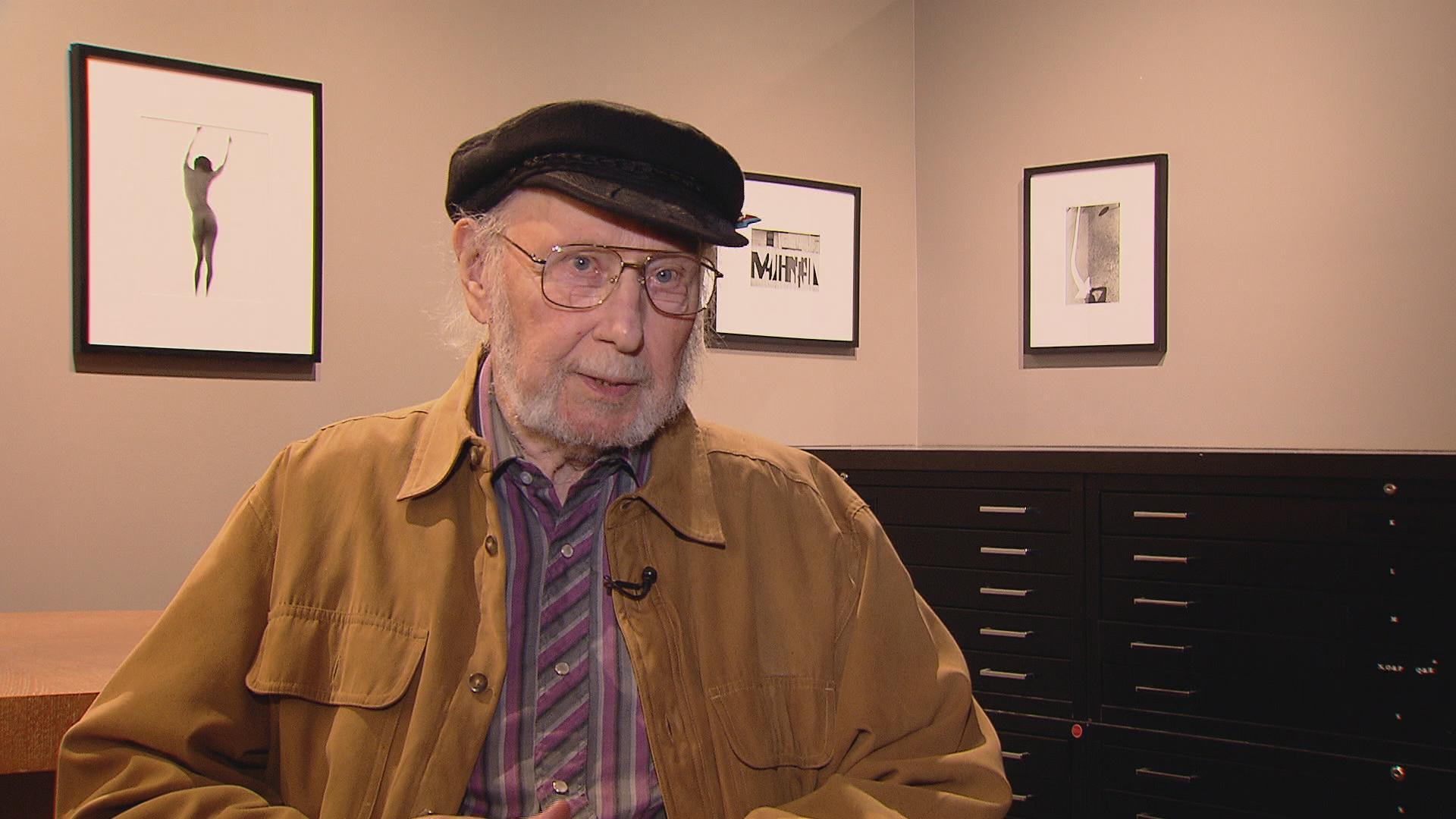

Kenneth Josephson

Kenneth Josephson

Ponce: Josephson continues to pursue series of photographs – thematically linked sequences that span more than 50 years of work. Josephson believes humor can add a lot to a picture.

Josephson: I think it’s a way of enticing someone to look at your work that there’s an in-road into the work, and maybe then they discover something else beyond just the humor.

Ponce: Kenneth Josephson’s work is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and many others institutions. A book spanning his career was recently published by the University of Texas Press. Locally, he has a long association with the Stephen Daiter Gallery. A native of Detroit, Josephson recalls his first impressions of Chicago as a young man.

Josephson: I was so impressed with the architecture here, and the lighting, especially in the Loop, that real strong highlight shadow thing that happens in sunlight, and there were so many things around in the city that could be photographed I was just so happy to be here. It was a great city for photography.

Ponce: And he is still making photographs.

Warren: I think it’s important to know that Ken has not only continued to work over the decades, that he works currently and he works in his darkroom, he prints his own work, he’s out there shooting still, and there’s some very recent representative photos of his past five or six years in the book.

Josephson: My primary work is in black and white, and I’m always looking at things in terms of value so that if I want to photograph something, I look for separation so that things stand out from the other things in the scene … So yeah, I’m really always looking for possibilities to photograph.

![]()

Below, an excerpt from “The Light of Coincidence: The Photographs of Kenneth Josephson.”

Foreword

Any photographer works in the context of their time and cannot help but be affected by it. So before we look at the work of Kenneth Josephson, it seems pertinent to review the general context of 1960s and 1970s American photography. It is perhaps an exaggeration to claim that Josephson has been underrated by the American photographic establishment, but nevertheless there is an issue with the kind of approach he and others adopted toward the medium in those heady days when photography was fighting for its place at the arts table – an issue concerning its reception in certain quarters.

As a result, this is something of a rehabilitation, a revisionist look at the legacy of an important photographic artist, rather in the manner of the recent reappraisal of the oeuvre of Wynn Bullock, another comparatively neglected figure, or Robert Heinecken, recently the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.1 There will be others also worthy of such fresh scrutiny – Jerry Uelsmann or Thomas Barrow, for instance. Indeed, a whole raft of figures may warrant this kind of attention: those who were perceived to be exploring the medium in a self-reflexive way, at a time when the most powerful institution in American photography, MoMA, was privileging photography "in the documentary mode."

John Szarkowski, then head of the Department of Photography at MoMA and widely regarded, not always with approbation, as the "czar" of American photography in the 1960s and 1970s, was interested primarily in the straight photographic aesthetic. He was considerably less enamored of those working in mixed-media techniques and those exploring the medium through the medium, rather than those exploring the world through the medium. At one point, Szarkowski's philosophical position was balanced by the presence in the photography department of Peter Bunnell, but Bunnell's initiatives, such as his groundbreaking exhibitions Photography as Printmaking (1968) and Photography into Sculpture (1970),2 were not repeated in quite the same way once he left the Modern to teach at Princeton, essentially leaving the field clear for Szarkowski and his deeply intelligent, perfectly valid, but largely purist view of photography.

Furthermore, as Andy Grundberg has noted, the kind of photography espoused at MoMA during Szarkowski's influential tenure remained "a distant cousin to the contemporary artworld of painting, sculpture, and Conceptualism."3

But here another issue arose. Photographic artists like Kenneth Josephson and many others, who were anything but traditional but who were regarded as traditional photographers, were squeezed on both sides, as it were, by the purism of Szarkowski on the one hand and by postmodern theory and a whole host of "artists utilizing photography" on the other. Just when photographers could think about hanging their work in the burgeoning number of photographic galleries that sprang up in the 1970s, and just as they could perhaps think about selling their prints as works of art, the whole notion of art photographic practice came under fire in postmodernist critical discourse, most devastatingly in Susan Sontag's 1976 book On Photography.4

Related Stories from "Chicago Tonight"

‘Bag Lady,’ Selfie Pioneer Lee Godie Gets Chicago Exhibition

‘Bag Lady,’ Selfie Pioneer Lee Godie Gets Chicago Exhibition

April 6: Self-portraits by the late outsider artist, taken in photo booths which used to accompany Chicago's bus stations, are at the center of a new exhibition opening Friday at the Intuit Art Center in Noble Square.

Photos Reveal Snapshots of City Neighborhoods in Late ‘70s

Photos Reveal Snapshots of City Neighborhoods in Late ‘70s

April 4: In 1978, photographer David Gremp spent a year documenting 14 Chicago libraries, their neighborhoods and their patrons. Gremp snapped hundreds of images, giving his subjects a simple directive: look straight into the camera.

Museum of Contemporary Photography Exhibit Captures Changing Medium

Museum of Contemporary Photography Exhibit Captures Changing Medium

March 28: In the Loop, a photographic feast is now being served. To celebrate its 40th anniversary, the Museum of Contemporary Photography combed its archives to find the pictures that best reflect the character of the museum. What they found were dramatic images from the 19th century to the 21st.