Geoffrey Baer investigates why the Loop’s streets honoring presidents don’t honor the order of their terms, returns to a North Side bridge to nowhere, and relates the sad story of the “radium girls” of Ottawa, Illinois.

![]()

Why are the streets in the Loop not named for the presidents in the order of their terms? Heading south – Washington, Madison, Monroe and Adams. The terms were Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Quincy Adams, Jackson and Van Buren.

– Jim Perry, The Loop

Not only do the presidents seem to be out of order, they’re not all even running in the same direction – Jefferson runs north-south, perpendicular to the rest of the streets.

For that, we can thank the surveyor who created the first plat map of Chicago in 1830, James Thompson, who created a very small grid of just a few streets around the Chicago River, from Dearborn to Des Plaines and Kinzie to Washington. At least two of the streets on that map have presidential names – Jefferson and Washington – as well as possibly Madison, though it wasn’t on the plat. But as it turns out, they may not be named (directly, at least) for presidents.

According to a 1953 Chicago Tribune article, Illinois politician and amateur historian Elijah M. Haines theorized that surveyor Thompson named the streets after the counties around his southern Illinois hometown of Kaskaskia, Illinois – some of which just so happened to be named for American presidents. Other streets named for downstate counties include Clinton, Franklin and Thompson’s own county, Randolph.

When Chicago’s street grid was expanded in subsequent years, additional streets were named to honor presidents including Monroe, Adams and Jackson.

As for Adams being out of order, Chicago street historian Tom NcNamee theorized that Adams Street is named for John Quincy Adams, and not his father. So it’s in the right order between Monroe and Jackson. To further support this theory, an alley between Adams and Jackson is named Quincy. McNamee figures that Chicago’s City Council didn’t like the elder President Adams’ highly conservative politics and skipped over him.

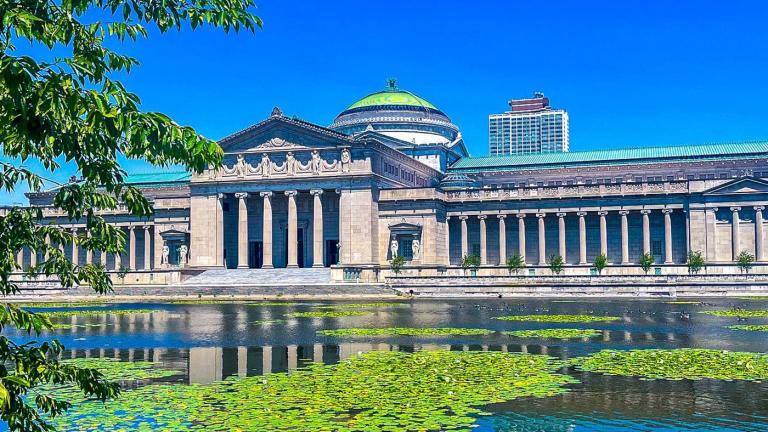

Adams Street at LaSalle Street (Ken Lund / Flickr)

Adams Street at LaSalle Street (Ken Lund / Flickr)

Presidential history enthusiasts will note President John Tyler was also skipped. However, there actually was a Tyler Street until at least 1890, and it was in between Van Buren and Polk, right where it belonged. Today, it’s Congress Parkway. One theory has it that when Tyler went from the Union side to the Confederate side after his term as president, the City Council changed the street name out of political disapproval.

If this sounds familiar, it’s probably because we just saw something like that again when our staunchly democratic City Council rescinded the name of honorary Donald Trump Way.

One last bit of presidential street serendipity. The Presidential Towers apartment complex in the West Loop was so named because when it was completed in 1986 it was bounded by two streets named for presidents – Madison and Monroe – and had a third presidential street, Jefferson, running through it. The street bordering the towers to the east was named after Erie Canal promoter DeWitt Clinton, but a decade later Bill Clinton was elected, so now the complex has presidential names on four sides!

![]()

What can you tell us about the Radium Girls of Ottawa?

– Rachel Rose, Joliet

(Courtesy Heinz-Dietrich Suppan)

(Courtesy Heinz-Dietrich Suppan)

In the 1920s, the Radium Dial factory in Ottawa, Illinois, southwest of Chicago, hired young women to paint watch and clock dials. To make the dials glow in the dark, the workers used paint containing the highly radioactive element radium. The women were instructed to use their mouths to give the brushes a fine point, a technique called lip pointing that would be repeated more than a thousand times in an average shift.

According to author Heinz-Dietrich Suppan, who wrote the book “Marking Time” about these so-called radium girls, sometimes the women would even paint their faces with radium for fun on their breaks.

Of course many of these workers developed alarming symptoms including brittle bones, tumors and anemia.

Suppan says Radium Dial suspected that radium was the culprit, but even as some women were dying from radium poisoning the company maintained that there was no such thing and said nothing to their employees.

In 1934 a group that called themselves Society of the Living Dead brought a lawsuit against Radium Dial. One worker testified at trial that she was fired for being visibly sick and scaring the other workers.

Eventually laws were changed and some workers got modest settlements.

That wasn’t the end of Ottawa’s radium problems, though. The radioactive material had not only made it into the workers, it made it into the soil and groundwater.

According to the EPA, 15 of 16 radioactive sites have been cleaned up, but work is continuing there to this day.

(Courtesy Heinz-Dietrich Suppan)

(Courtesy Heinz-Dietrich Suppan)

The radium girls are memorialized in Ottawa with a bronze figure of a young woman holding a paintbrush and a wilted tulip that was erected in 2011. The campaign to build the monument was started by a 7th grader named Madeline Piller in 2007.

By the way, radium is no longer used in watches and clocks sold to the public. Today’s glow-in-the-dark timepieces use non-radioactive phosphorescent compounds or in some cases, a weak radioactive element called tritium that is not harmful.

![]()

What was the tall bridge on Grand Avenue and Fullerton by the Brickyard shopping center?

– Mark Gubernat, Arlington Heights

It wasn’t a bridge – if anything, it looked more like half a bridge, or maybe a truncated on-ramp to an expressway – it was actually a mobile radar test track that Western Electric built in 1943 to test mobile radar equipment.

Mobile radar units would drive up a wooden ramp to get onto the track and drive to the top, about 40 feet up. Planes from Glenview Naval Air Station would fly over and the radar units to collect data, which would then be used to evaluate the equipment’s efficiency.

The area around Grand Avenue and Fullerton is on a ridge – in fact a few blocks away from where Chicago’s only ski resort once stood – so it was a lofty perch for Chicago that kept it clear of ground echoes.

Radar was at the time a new technology that wound up being crucial to American success in World War II.

The track was used throughout WWII and the Korean War, but after that the wooden ramp was removed. It sat unused for more than three decades because it was too costly to tear down. It was finally demolished in the 1990s and replaced with a strip mall.

![]()

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.