When a person with celiac disease consumes gluten — a protein found in wheat, rye and barley – it triggers an immune system response to attack the lining of the small intestine.

When a person with celiac disease consumes gluten — a protein found in wheat, rye and barley – it triggers an immune system response to attack the lining of the small intestine.

Nearly 3 million Americans have celiac disease, and a new study links a common but otherwise harmless virus to the condition.

While it doesn’t cause celiac disease, the asymptomatic virus can trigger an immune system response that leads to the disease’s development.

“What’s striking about this study is in the background a virus that produces no overt clinical symptoms [can] profoundly change the way the immune system sees a dietary protein, and it sets the stage for celiac disease,” said the study’s senior author Dr. Bana Jabri, professor and director of research at the University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center.

Celiac disease is an inherited autoimmune disorder that affects the small intestine. Despite the prevalence of the disease – 1 in 133 people in the U.S. are impacted by it, according to the study – only 17 percent of Americans have been diagnosed with it.

When a person with the disease consumes gluten — a protein found in wheat, rye and barley – it triggers an immune system response to attack the lining of the small intestine.

Symptoms range from abdominal bloating and pain, to diarrhea, constipation, anemia, fatigue, joint pain and unexplained infertility – and some people don’t have any symptoms. There is no cure for celiac disease; a gluten-free diet is the only treatment at the moment.

While about 40 percent of Americans are genetically susceptible to developing it, only about 1 percent do, Jabri said. “The question has always been, ‘What can trigger celiac disease in the 1 percent of the population when we know 40 percent of people have that gene?’”

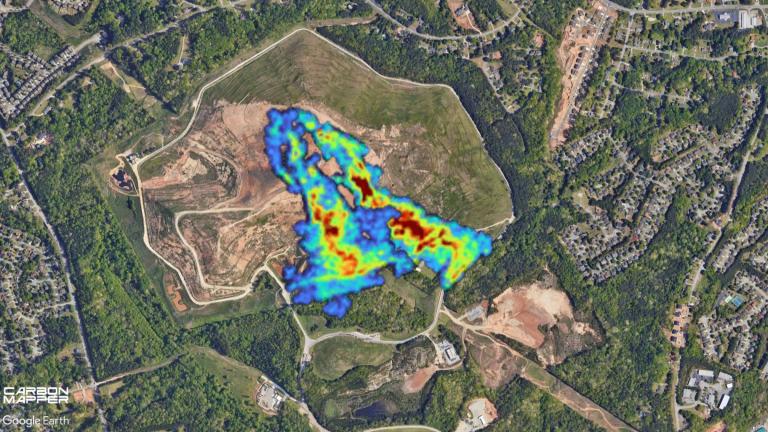

Since viruses are known to trigger inflammatory responses, researchers wondered if a virus could lead to the development of the disease. To test this, mice were infected with two common human strains of reovirus, a harmless virus that can occur frequently throughout a person’s life.

“What we want to see is to try and define what characteristic a virus had to have to cause a disruption,” Jabri said. Both reovirus strains induced a protective immune response when tested on mice, allowing them to clear the virus without developing overt clinical symptoms.

Before being infected with either reovirus strain, mice didn’t have an inflammatory response to gluten. But after the infection, one of the viruses “changed the way the immune system sees [gluten] and triggered an inflammatory response against that protein,” Jabri said. The reovirus also triggered the loss of oral tolerance to gluten, according to the study.

The other reovirus strain, though closely related but genetically different, did not produce the same immune system response.

“We have been studying reovirus for some time, and we were surprised by the discovery of a potential link between reovirus and celiac disease,” said Dr. Terence Dermody, co-author of the study and chair of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine’s department of pediatrics, in a press release.

“We are now in a position to precisely define the viral factors responsible for induction of the autoimmune response.”

![]()

“We don’t have proof yet but it could be the timing of the infection and gluten introduction that matter.”

–Dr. Bana Jabri

In the study, researchers also investigated whether there was a defining characteristic for reovirus in celiac disease. “We found a subset of celiac disease patients had very high antibody titers against reovirus that was much higher than the control group,” Jabri said. “Those patients actually had this activation of inflammatory pathway in their intestine, and we know that because when they’re diagnosed with celiac disease we do a scope or biopsy.”

The study also found that patients who had higher levels of antibodies against the reovirus had higher levels of a specific gene expression that plays an integral role in the loss of oral tolerance to gluten.

Since reovirus silently changes the body’s natural immune response, researchers propose that after the initial infection the body begins building up an anti-gluten army.

“The reovirus could be one trigger that starts this, and then you have another infection that could increase this army of inflammatory immune cells that are specific for gluten,” Jabri said. “And then once a certain threshold is reached, you have celiac disease.”

Researchers are interested in studying whether other viruses or microbes play a role in the development of celiac disease, as well as how the timing of an infection plays a role.

“We don’t have proof yet but it could be the timing of the infection and gluten introduction that matter,” Jabri said.

In America, many children are introduced to solid foods – many of which contain gluten – around the same time they experience an initial viral infection.

“During the first year of life, the immune system is still maturing, so for a child with a particular genetic background, getting a particular virus at that time can leave a kind of scar that then has long-term consequences,” Jabri said.

For a child with a genetic predisposition to celiac disease, a reovirus infection could set the stage for its development. Once more studies are completed, Jabri says it’s worth discussing whether children at risk of developing celiac disease should be vaccinated.

Follow Kristen Thometz on Twitter: @kristenthometz

Related stories:

Prevent Peanut Allergies: Give Kids Peanuts

Prevent Peanut Allergies: Give Kids Peanuts

Jan. 6: Infants as young as 4 months old should be introduced to peanut-containing foods to prevent the development of peanut allergies, according to new guidelines.

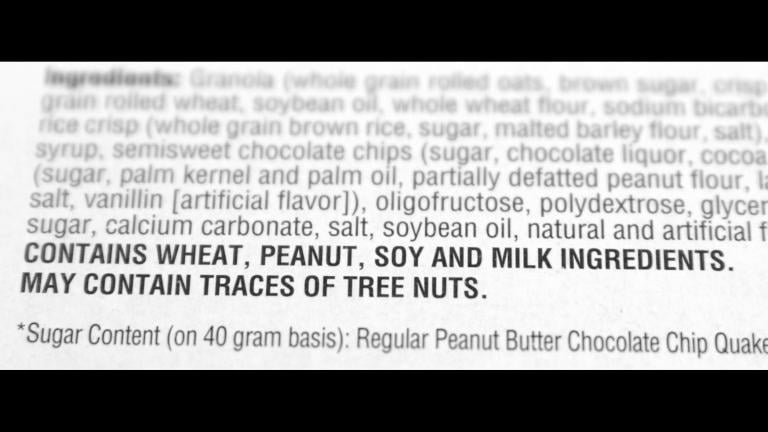

What You Need to Know About Food Allergy Labels

What You Need to Know About Food Allergy Labels

Nov. 25, 2016: What does it mean when a food label says it “may contain” peanuts or was “processed in a facility” that also uses peanuts? A local pediatrician explains what these labels mean and why consumers should be wary of them.

The Microbiome’s Role in Precision Medicine

The Microbiome’s Role in Precision Medicine

Nov. 16, 2016: Inside the human body lives a community of microorganisms, bacteria, viruses and fungi known as the microbiome. Local professors talk about the importance of understanding the microbiome and the potential implications it could have on health and disease.