Recovering from a heroin or other opioid addiction can be a daunting task, one more and more people are faced with since the country’s opioid crisis has surged.

But like other chronic illnesses, relapsing during treatment of addiction is not only possible, but likely.

One form of treatment is called medically assisted treatment and involves providing patients a different drug to help transition off the more serious, highly addictive opioids.

We take a look at how it’s working for recovering addicts at Heartland Alliance’s Supportive Treatment for Addictions and Recovery Team.

![]()

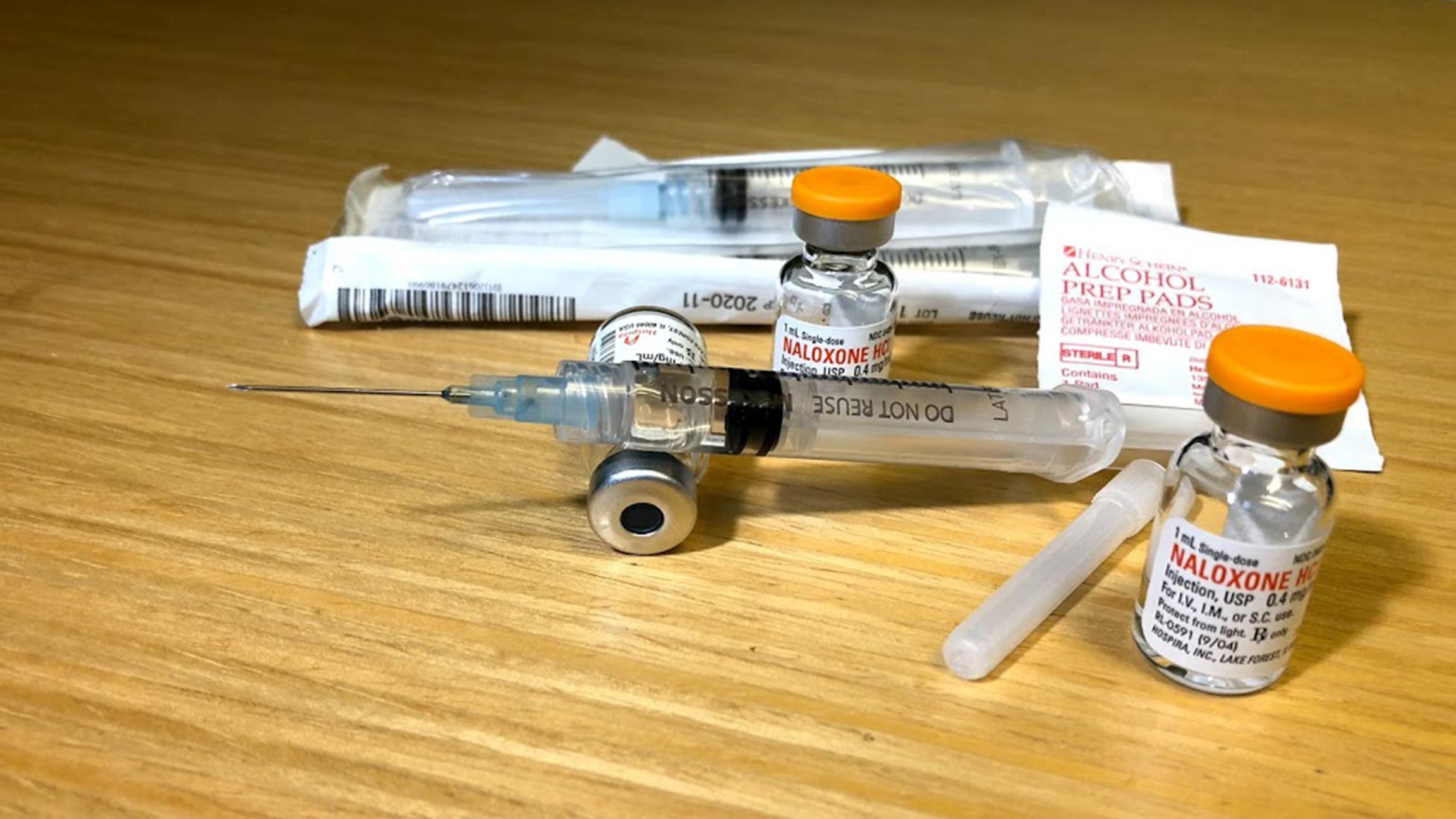

A tiny vial with a milliliter of medicine could be all it takes to stop a heroin overdose in its tracks.

“I make hundreds of these,” says therapist Ursula Wagner of Heartland Alliance’s Supportive Treatment for Addiction and Recovery Team. She gives the packages of naloxone to staff members and program participants.

One of those participants was 56-year-old Cleveland Hester. He knows both what an OD looks like, and feels like.

“I was a heroin addict, and I used every day, sometimes maybe six or seven bags or more a day. I have overdosed at times,” he said.

Hester says he used for years, starting as a teenager. Before long, he found the inevitable downward spiral that comes from abusing opiates.

“It relaxed me,” Hester said. “At first I did it for fun, but after you constantly use, it’s no longer fun, because you don’t have the money to get it, you do things that you normally wouldn’t do, steal.”

Today, he can say he’s sober, receiving medically assisted treatment from the Supportive Treatment for Addictions and Recovery Team.

“Now, I don’t use at all. I take Suboxone strips,” he said.

Suboxone is the drug that lessens the severe symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Hector said he experienced sweats, stomach ache, diarrhea and vomiting.

But still, he kept using. “If I didn’t, I could have died,” he said. “I felt like I was dying.”

“When someone is coming off of an opiate high or a heroin high, they’re left with a brain that is not producing other things to make them feel good,” Wagner said. “There’s physical sickness that comes with it.”

Hester’s therapist explains that we’re all born with endorphins in our brain. When we do things that make us feel good, like eat food or exercise, we get tiny endorphin rushes. But when the brain starts receiving opioids, it can’t compete with the flood it receives of something far stronger than natural endorphins. Eventually, endorphin production slows, and it takes time to resume even long after drug use ends.

And giving the drug up, either with treatment or by going cold turkey, is hard, to say the least.

“I struggled at first for a while,” Hester said. “I went from using every day to then just using on the weekend, which for me, that was a long way from where I’d been.”

Wagner explains that progress valued at the Supportive Treatment for Addictions and Recovery Team may not always look like the progress everyone expects to see.

“One of (Hester’s) big milestones, I remember, was moving from using every day to using every other day. That was a really big step,” she said.

Because the intent is to reduce harm, the center still helps participants even when they’re using drugs.

“A tough-love approach is counterproductive to people’s healing,” Wagner said. “They will just sort of give up and say, ‘If messed up once, and that’s it, and I’ve lost all my progress, then what’s the point of even trying at all?’ We know that they’re safer, so that’s one reason we don’t want to kick them out.”

And after years of drug abuse, healing can take just as long.

“A lot of the people that we’re working with that are struggling with opioid addiction have been using for many, many years,” said Matt Cuddeback, supervisor of Heartland Alliance’s Supportive Treatment for Addiction and Recovery Team. “So the idea of suddenly just being able to stop … it’s not entirely realistic. It takes a little bit of time … to get to a point where they’re also able to address some of the underlying issues.”

So here, there’s no rush to get off Suboxone.

“It’s stigmatized because it’s for a substance use disorder, which is a medical disorder. If someone had to be on insulin for their diabetes, we wouldn’t say, ‘Oh gosh, we want to get them off that insulin as soon as possible,” Wagner said.

Even if they use the drug for the rest of their lives, advocates here say it’s far better than continuing to abuse opiates.

![]()

The Heartland Alliance says participants in this program are referred from emergency rooms, other treatment centers and word-of-mouth, since Heartland Alliance already serves many people in the city’s homeless population.

Note: An earlier version of this story referred to the Midwest Harm Reduction Institute, within which the Supportive Treatment for Addictions and Recovery Team operates.

Follow Brandis Friedman on Twitter @BrandisFriedman

Related stories:

5,000 Doses of Lifesaving Narcan Donated to Illinois

5,000 Doses of Lifesaving Narcan Donated to Illinois

Feb. 9: Officials battling the state’s opioid epidemic got a boost this week with the donation of a medicine that reverses the effects of opioid overdoses. In 2016, nearly 1,950 people died of opioid overdoses in Illinois.

Illinois Health Officials: State Facing ‘Unprecedented’ Opioid Epidemic

Illinois Health Officials: State Facing ‘Unprecedented’ Opioid Epidemic

Jan. 4: Opioid overdoses in Illinois claim more lives than homicides and car accidents. State health officials tell us what’s behind the crisis.

Chicago Photographer Captures Toll of Opioids, Homelessness

Chicago Photographer Captures Toll of Opioids, Homelessness

Dec. 28, 2017: Lloyd DeGrane spent three years photographing homeless encampments in Chicago. He shares images and stories from the streets.