Baseball is back on the field in Chicago, and our viewers have some hardball questions about our city’s storied baseball teams.

![]()

An old, old-timer told me that the Cubs and White Sox would play an exhibition series every October, after the regular season. He said Major League Baseball stopped the series because it took attention away from the World Series. Is this true?

—Richard Soska, Evanston

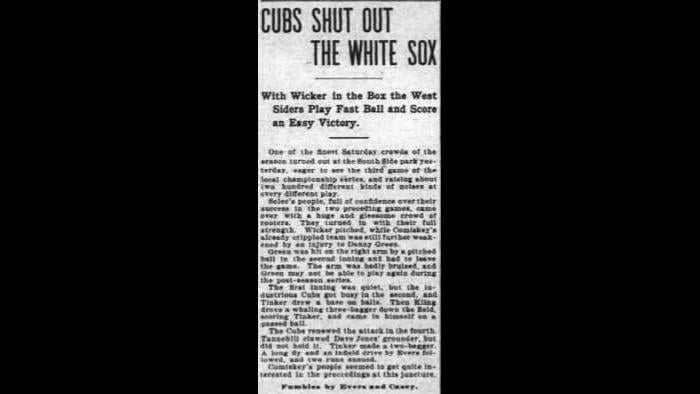

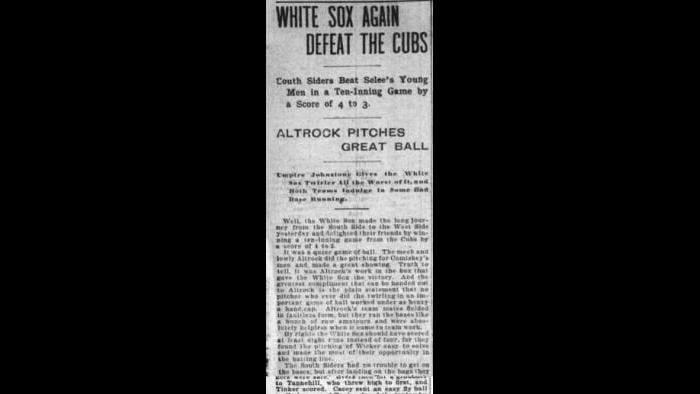

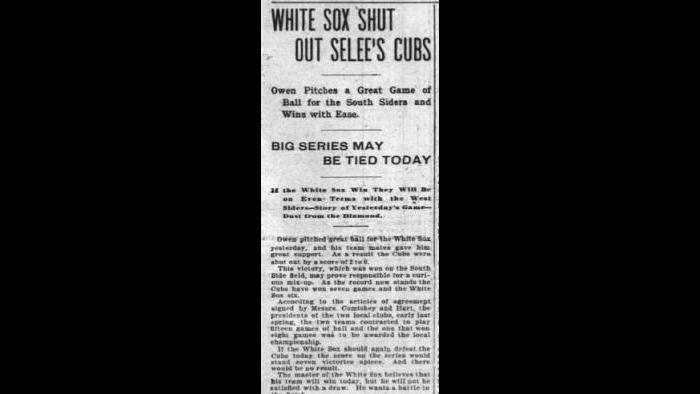

Your old, old timer friend is right – back before interleague play began in 1997, the Cubs and White Sox faced each other in an October series they called the “City Series” 26 times between from 1903 to 1942. But while the games were popular with fans, we couldn’t find any evidence that Major League Baseball wanted to stop them.

The first City Series in 1903 was cooked up by the teams’ owners, Charles Comiskey of the White Sox and James A. Hunt of the Cubs. They agreed to play a 15-game series – yes, 15! – in October, alternating between Comiskey Park and the Cubs’ West Side Grounds.

Cubs vs. White Sox City Championship Series, October 1909

Cubs vs. White Sox City Championship Series, October 1909

The teams alternated wins, too. Though the favored Cubs won the first three games, the Sox kept battling back. By the 14th game they were tied at seven games apiece. And that is how the series ended – in a tie. The Cubs refused to play the 15th game, reportedly because, among other things, the Cubs’ shortstop Joe Tinker was getting married that afternoon in Kansas City and would not postpone his wedding. The Sox offered to play a double-header at Comiskey on the last day, but the Cubs declined, saying it would give the Sox an unfair advantage.

The Cubs also declined to play a City Series the following year, but when the North Siders (well, at the time, West Siders) got a new owner in 1904, the series began anew. After that, whenever both teams were not in the World Series, the team who lost the previous series would issue a challenge to their rivals.

Over the 26 City Series, the South Siders won 19 of the 26 City Series to the Cubs’ paltry six wins.

In 1906, the teams didn’t play a City Series because they were both playing in a more important one – the World Series! So far that was the only time the crosstown rivals played each other for the championship, and the Sox won that series too, four games to two.

But that was far from the end of the Cubs-Sox face-offs. Most years they continued to play each other in preseason series. From 1943 to 1948, they played against each other for war bonds each April. From 1949 to 1972, they played a game each season called the Boys Benefit game to support youth baseball in Chicago – the Cubs fared better in those matchups, winning 13 years to the Sox’ 10.

The teams played twice following the players’ strike in 1981 at Mayor Jane Byrne’s suggestion; the Cubs won one of those games and the second ended in a tie.

West Side Grounds, 1906

West Side Grounds, 1906

And from 1985 to 1994, the teams revived the rivalry with one-game face-offs to benefit team charities called the Windy City Crosstown Classic. In those years, the Sox bested the Cubs eight times. The other two ended in ties.

But all of those series were exhibition games – they didn’t count, except to fans. Now when the Cubs and Sox face off, it counts, and even though the Cubs have had more recent success than the Sox, the South Siders still hold the edge there. In the 108 games they’ve played since 1997, the Sox have been victorious 56 times, and the Cubs 52 – including the infamous 2006 game where the Cubs’ Michael Barrett punched the Sox’s A.J. Pierzynski.

This year they play each other six times, so the Cubs have a chance to even the score – and hopefully, without any punches getting thrown.

![]()

Around 1970, the Cubs had to install a chain-link fence around the outfield bleachers to keep fans from jumping on to the field, creating a basket. Since the installation of the basket, have the total of home runs registered by the Cubs exceeded the total of home runs hit by all of the opposing teams?

—Sue Bloecks, LaGrange

We asked the Cubs’ historian Ed Hartig, and he said that since the basket was installed a couple of weeks into the season in May 1970, as of April 12, 2018, the Cubs have hit 3,893 homers at Wrigley, and their collective opponents have hit 3,866 – a difference of just 27 home runs over 48 years. Statistically speaking, that’s barely a blip.

As our viewer mentions, the reason the basket was installed was to stop fans in the bleachers from falling or jumping onto the field, which was an issue during the raucous 1969 season.

That was the year the Cubs, with stars Ernie Banks, Ron Santo, Billy Williams and Fergie Jenkins, led the National League East for much of the season and it looked like the curse might finally be broken until the Cubs swooned in August and the Miracle Mets won the pennant.

At the time, die-hard Cubs fans in the left field bleachers who called themselves the “Bleacher Bums” had become famous for their rowdy and often drunken antics. WTTW even produced a TV version of the Organic Theatre’s play about the Bleacher Bums with some young actors who became pretty big names, including Dennis Franz and Joe Mantegna.

There were enough incidents of fan interference and wall-hopping by the Bleacher Bums and others that Cubs fans management installed the fence in May 1970. Since then the outfield basket, as it commonly known, has become one of the quirks that make Wrigley, well, Wrigley – and it’s caught its share of overzealous fans since it was put up.

The 42-inch-high fence angles out from about 30 inches from the top of the wall at about 45 degrees. The wall is about 11.5 feet high. So the basket effectively moves the outfield wall in about 30 inches, which means that a ball that might have been a double or a long fly out sometimes turns into a run.

While it might not be a factor long-term, the basket has come into play during some pretty big games. In Game 1 of the 2016 National League divisional series against the San Francisco Giants, Cubs infielder Javy Baez hit a ball that just barely cleared the basket for the only run of the game. When Giants fans complained that it was a cheapie home run, Baez tweeted: it still went out.

But what the basket giveth, the basket taketh away. In 2017, the Washington Nationals’ Michael Taylor knocked a grand slam into the basket, lifting the Nats to a win in Game 4 of that divisional championship.

We asked a few experts whether the basket makes Wrigley Field more of hitter-friendly park, including Ed Hartig, historian Stuart Shea, and historian and researcher Bill Felber. All three believe that, given how many other factors go into home run hitting, the basket has had little effect on Wrigley’s hitter-friendliness. Shea adds, “It's given rise to the ‘in the basket’ term, I suppose, but I have never liked it, as I feel that it just increases cheap home runs. I think the decision to install it in 1970 was a paranoid response to a few fans jumping over the fence, and getting rid of the basket would go a long way toward making Wrigley Field more fun and accessible.”

Bill Felber supplied us with some additional analysis of the question – here are his thoughts:

Has the 1970 installation of a basket in front of the outfield wall at Wrigley Field made a statistical difference in the number of home runs hit?

Let’s begin with a few facts. The basket was installed in May of 1970. Its leading edge extends three feet out from the top of the wall and even with the wall’s top, making this superficially a fairly easy question to answer. At any given point, it’s three feet easier to hit a home run. From an isolated physical standpoint, there’s a bit more to it than that, but not much. Since the wall is effectively moved in by three feet, the barrier – generally 11.5 feet in height – becomes a bit more difficult to surmount. As an exaggeration to make the point, imagine trying to hit a ball over an 11.5 foot wall 370 feet away. Now move the same wall up to within five feet of you. The closer the wall is, the more it is necessary to adjust one’s swing arc to accomplish the feat. But that’s a technical distinction: the difference between 370 feet and 367 feet is just eighty-one hundredths of one percent, so we’re not talking about enough of a swing change to worry about. You probably figured that out already.

To answer this question in its simplest terms, we can begin with the data. Let’s compare the last full pre-basket season played at Wrigley Field – that would be 1969 – with the first full post-basket season, 1971. In 1969 the Cubs and their opponents combined to hit 144 home runs. (Since no distinction is made in the records between inside-the-park home runs and those hit over the wall, it’s theoretically possible that not all 144 left the playing field…but let’s assume they did. Our guess would be that “moving the wall” in by three feet ought to have increased home run frequency between 1969 and 1971. In fact, during the 1971 season 143 home runs were hit during games played in Wrigley Field, one fewer than in 1969. There is, however, a minor ‘kicker’ in our data. On June 7, 1969, the Cubs and Cincinnati Reds played a 9-inning, 5-5 tie game that was halted – presumably by darkness -- and later replayed in its entirety. That means there were 82 games played at Wrigley Field in 1969, not 81. So we need to recalculate our home run data on a per-game basis. When we do that, we find this:

HR per game

• 1969: 1.76

• 1971: 1.77

So technically Wrigley Field was statistically a slightly better home run park immediately following the installation of the basket than immediately before. But of course there are so many weaknesses in that generalization that it’s hardly worth stating. The first is the simple element of random chance. I’m not enough of a mathematician to calculate the normal variation of expected home run performance at Wrigley over the course of a season, but I double guarantee it’s greater than one. A second factor is the changing nature of the talent base. Just to pick an obvious example, in 1969 Ernie Banks (my childhood hero) hit 15 home runs at Wrigley Field; in 1971, he hit two. Weather is a third vital variable.

So far we have examined the question only from a short-term perspective. You actually asked a more general question – how has the basket affected home run hitting generally? -- inviting a more long-term answer. I cannot give that answer…at least not in isolation. Home run hitting is affected by a significant interplay of factors, only one of which – and a fairly small one – is whether the barrier is 3 feet closer or farther. The necessary analysis could be done with particular respect to Wrigley Field, and I’d be happy to do the substantial work necessary to provide it in exchange for a suitably large cash stipend. Failing that, let’s look a home run rates generally across time; that should illustrate the issues. In 1969, National League teams averaged three-quarters of a home run per game. (We’ve already established that Wrigley Field performed at almost exactly that figure.) In 1971, the average was .71 home runs per game league-wide; since Wrigley’s rate was higher, at least part of that difference might be attributed to the basket. But look what’s happened to home run rates since 1971. By 1987, they had risen league-wide to .94 per game. In 2007 (following implementation of inter-league play, which brings in the DH and thus muddies our calculations) the average was 1.02. Last year it was 1.26. Plainly something is going on that doesn’t involve baskets at Wrigley Field, and that something speaks to the heart of the problem. Far more significant to any change in home run numbers than a three-foot relocation of the wall are a host of factors that boil down to one simple word: approach. Players are abstractly bigger and more powerful, making them more capable of swinging a bat faster, a fact that translates to longer ball flight. Players also appear more willing to swing harder, a risk-reward calculation that trades the threat of a strikeout for the gain of a long ball.

I cannot measure these factors precisely with respect to production at Wrigley Field, but you can measure them on your home computer through the aegis of people who know a lot about flight. In 2014, with an eye toward encouraging the study of physics, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) created a website designed to allow a user to study how to optimize ball flight. You can use this link to visit the site. Among the variables that have a greater effect on ball flight at Wrigley (or anywhere else) than a 3-foot wall adjustment are: the weather (temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, wind speed), the speed and spin rate of the pitch, the speed and launch angle of the swing, the coefficient of restitution of the bat and ball, and the angle of flight. Change any of those factors and you’ll learn that relatively minor adjustments can influence ball flight by five or more feet…more than the installation of the basket.

By the way, high school students into baseball or softball and needing a physics project may find inspiration at the NASA site.

Note: The respondent, Bill Felber, is a native of Chicago, a retired newspaper editor, and the author of seven books, most of them on baseball. His eighth book, “The Hole Truth,” applies SABRmetric principles to rank the greatest players in the history of golf. It will be published by Bison Press in the fall of 2018.

![]()

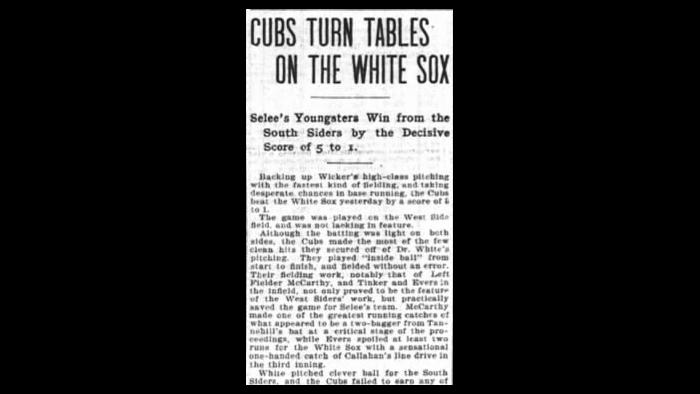

Jack Brickhouse and Ernie Banks

Jack Brickhouse and Ernie Banks

Who dreamt up the title The Friendly Confines?

—Dick Baer, Northbrook

According to Cub historian Ed Hartig, Mr. Cub himself, Ernie Banks, referred to Wrigley Field as the Friendly Confines sometime around 1956. Hartig says that Banks recounted driving up to the ballpark on the team bus after a tough road trip. He turned to his teammate Jerry Kindall and said, “it certainly feels good to be back at the Friendly Confines.” Banks said legendary Cubs broadcaster Jack Brickhouse heard him saying the phrase and got Banks’ permission to use the phrase to describe Wrigley Field during his WGN broadcasts, and it took off from there.

But Banks didn’t coin the phrase. By 1956 it was in frequent use to describe the home field for any number of teams in all kinds of sports.

The Cubs painted the phrase “Welcome to the Friendly Confines of Wrigley Field” on the roof of the opposing team’s dugout at Wrigley in 1982. That’s the only place you’ll see the phrase on Wrigley Field, but you see it all the time on Cubs merchandise.

![]()

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.