She is a poet, sociologist, podcaster and now: comic book writer. Eve Ewing’s list of professional titles keeps growing, but her focus on Chicago Public Schools endures. And her interest is not just academic – it’s personal.

Ewing was a CPS student and taught students in sixth, seventh and eighth grade at Pershing West Middle School from 2008-11 – one of 50 CPS schools slated for closure in 2013.

“That was a shocking, stunning moment for me,” Ewing said of her initial reaction to the news. She was a student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education at the time.

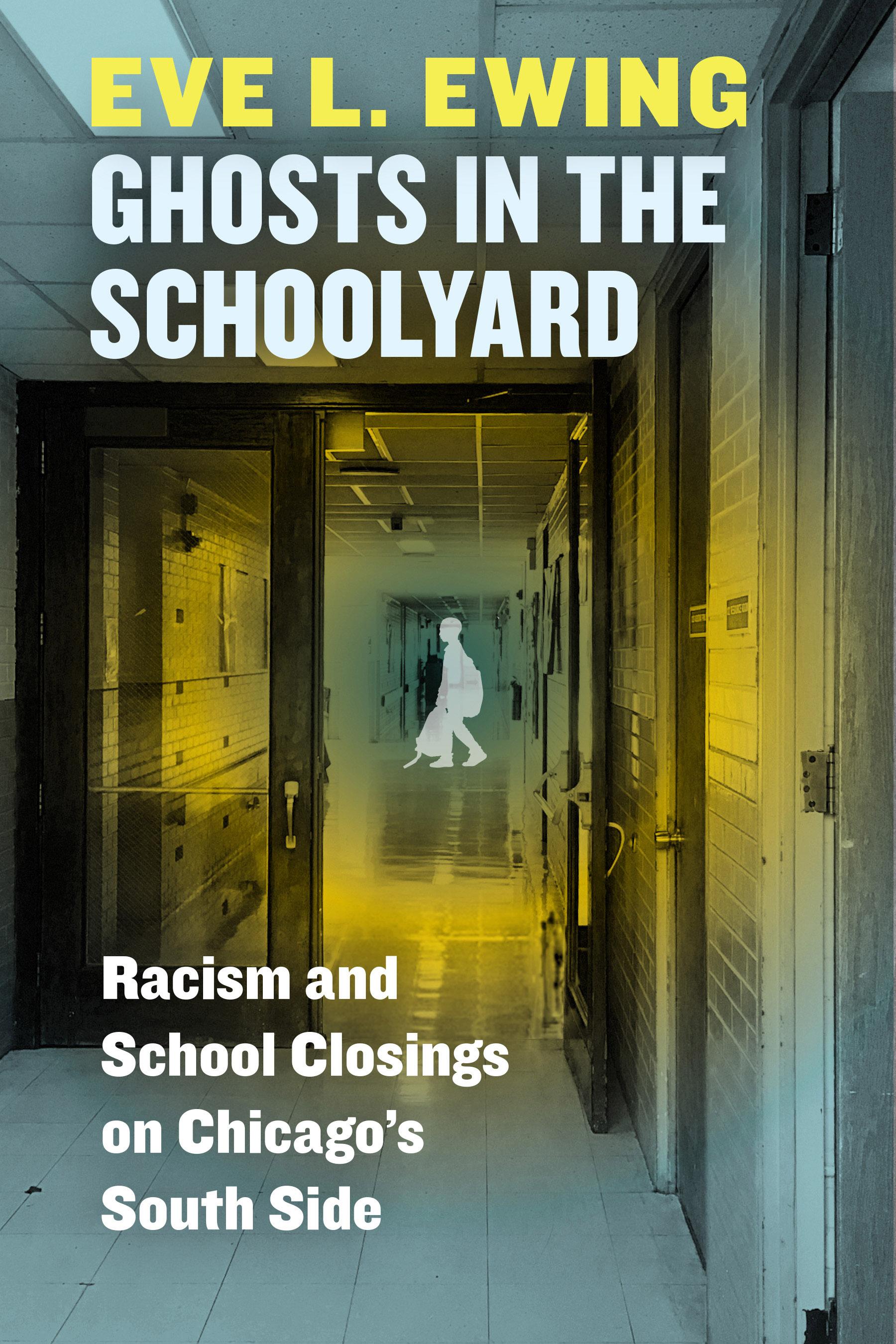

And that’s what drove her to write her recently released book “Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side.” The book grew out of her dissertation at Harvard, and in it she looks at what caused those school closings, in addition to the forces it unleashed, the aftermath and the lessons.

But the book also highlights how Americans talk about race and racism, Ewing said. And at the heart of that discourse is the difference in how former CPS CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennet and former Chicago Teachers Union President Karen Lewis talked about the school closures.

“Barbara Byrd-Bennet framed that as an unfortunate consequence,” Ewing said, adding that because Byrd-Bennett is black, she said she wasn’t capable of conducting a racist action.

“And people like Karen Lewis ... understand racism to be more of a structural thing,” she said. “It’s something that lives outside of individuals, and when we measure racism, we have to talk about impact and not intention.”

The impact of those closures? Ewing said 88 percent of the students affected by the closures were black.

“That is a racist impact,” she said.

Race also comes up in the premiere of “Bughouse Square,” a new WFMT podcast that pulls together archived interviews by radio legend Studs Terkel and commentary from Ewing.

Episode 1, released Oct. 5, features a 1962 conversation between Terkel and author James Baldwin on his novel “Another Country.” The episode later turns the table to offer a modern-day perspective on black writers from Ewing and guest Darnell Moore, former editor-at-large at CASSIUS and head of strategy and programs at BreakthroughUS.

“It’s almost uncanny of how [Baldwin’s] insights from 50 years ago have so much to teach us about the world today,” Ewing said. “That’s the fun thing about the podcast – you can hear these old conversations, but they sound like they could have been yesterday.”

Episode 2 is released Friday, and “Ironheart” – a Marvel comic written by Ewing – is set to take flight Nov. 28.

The story is centered on Riri Williams, aka Ironheart, a former mentee of Ironman who builds an “iron” suit of her own.

“But what’s really cool, of course, is that she’s a Chicagoan, and so it’s really a special story for me to be able to tell,” she said.

Ewing joins us to discuss “Ghosts in the Schoolyard,” what she learned from listening to Terkel’s interviews and what attracts people to superheroes.

Below, an excerpt from “Ghosts in the Schoolyard.”

For an August day in Chicago the weather is unseasonably cool, and many of the people sitting in the park have blankets draped over their laps or around their shoulders. In many ways this looks like any family gathering in Washington Park—older faces and younger faces in a circle of fabric lawn chairs and coolers, chatting amiably. But rather than pop, picnic food, or snacks, many of the coolers are filled with infused water or high-nutrient juices. Thermoses of hot broth are propped against a tree. And there are people here you wouldn’t see at a family picnic: visitors from across the city, reporters and photographers from across the country. Worried nurses flit from person to person. No music is playing. Sometimes folks laugh and joke cheerfully; other times they look off into space, exhausted. Behind it all a tremendous black building looms, its windows dark. And that is the reason these people are here—not for any family reunion or summer gathering, but in the name of this shuttered building, Walter H. Dyett High School. They are not picnickers, they are hunger strikers. And they are putting their lives on the line in hopes of seeing their vision for this school become reality.

Why do people fight for schools like this? While the Dyett hunger strike would rise to public prominence as one of the most visible examples of community members fighting to save a school, it is hardly the only one. Across the country, school stakeholders who are culturally and geographically very different have waged notably similar battles to get their schools off district chopping blocks. In Detroit in 2017, hundreds of parents and community members rallied in front of the state of Michigan’s offices to protest the closing of schools that others referred to as “consistently failing” and “the worst of the worst.” In Shreveport, Louisiana, in 2011, parents held meetings and circulated a petition to save Blanchard Elementary, which the district called “small,” “lacking,” and “old.” In Austin, Texas, in 2016, parents organized high turnouts at community meetings and picketed to fight the district’s closure of ten schools it said were in poor physical condition and underenrolled.3 In Dyett’s case the media declared that “by just about any definition [the school] has failed.” To outside observers—concerned neighbors and friends, informed citizens reading about education issues in the news or seeing these protests on television—it may be hard to reconcile these characterizations. If the schools are small, the worst, lacking, and so on, why is anyone fighting for them? This question may be amplified by the image of public schools we see and hear in the media, from A Nation at Risk to Dangerous Minds. As someone who attended public schools and later taught in one, I can’t count how many times a stranger remarked to me in casual conversation that I was an “angel” or a “saint” because public schools were “just so bad,” with no clear reasoning about why or in what way. This chapter tells the story of one group of people fighting to keep a school open—and, moreover, to see it reflect their vision for their community and their children’s education. We see that this community’s choice to resist a school’s being characterized as “failing” is in fact about much more than the school itself: it is about citizenship and participation, about justice and injustice, and about resisting people in power who want to transform a community at the expense of the people who live there.

Why do people fight for schools like this? While the Dyett hunger strike would rise to public prominence as one of the most visible examples of community members fighting to save a school, it is hardly the only one. Across the country, school stakeholders who are culturally and geographically very different have waged notably similar battles to get their schools off district chopping blocks. In Detroit in 2017, hundreds of parents and community members rallied in front of the state of Michigan’s offices to protest the closing of schools that others referred to as “consistently failing” and “the worst of the worst.” In Shreveport, Louisiana, in 2011, parents held meetings and circulated a petition to save Blanchard Elementary, which the district called “small,” “lacking,” and “old.” In Austin, Texas, in 2016, parents organized high turnouts at community meetings and picketed to fight the district’s closure of ten schools it said were in poor physical condition and underenrolled.3 In Dyett’s case the media declared that “by just about any definition [the school] has failed.” To outside observers—concerned neighbors and friends, informed citizens reading about education issues in the news or seeing these protests on television—it may be hard to reconcile these characterizations. If the schools are small, the worst, lacking, and so on, why is anyone fighting for them? This question may be amplified by the image of public schools we see and hear in the media, from A Nation at Risk to Dangerous Minds. As someone who attended public schools and later taught in one, I can’t count how many times a stranger remarked to me in casual conversation that I was an “angel” or a “saint” because public schools were “just so bad,” with no clear reasoning about why or in what way. This chapter tells the story of one group of people fighting to keep a school open—and, moreover, to see it reflect their vision for their community and their children’s education. We see that this community’s choice to resist a school’s being characterized as “failing” is in fact about much more than the school itself: it is about citizenship and participation, about justice and injustice, and about resisting people in power who want to transform a community at the expense of the people who live there.

The Dyett Tradition

So much of black life in Chicago happens in Washington Park that if you are African American, even if you are from the West Side or (like me) the North Side, it is hard not to find yourself there at least once each summer. The African Festival of the Arts, the Bud Billiken Parade, and family barbecues all find a home in the massive park. Sitting at the southern edge of Bronzeville, it covers 367 acres landscaped by Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect most famous for his design of New York City’s Central Park. At the northern end of the park, facing Fifty-First Street, a low building of black glass looks out over a broad expanse of grass. In summer 2015 the building is empty, but the flag still flies above it. The sign still says “Welcome to Walter H. Dyett High School” in black against a yellow background, bright against the backdrop of the dark building and Chicago’s more often than not gray weather. But no doors are open. No teenagers gather to talk or to run, to flirt or gossip or tease, to play football or scramble for forgotten homework or do the things teenagers do. Walter H. Dyett High School is closed.

Not many schools are named after teachers, so it is notable that this building is as much a living monument to Walter H. Dyett as it is an educational institution. It is also notable that this man, arguably the most renowned and respected educator ever to emerge from Bronzeville—a community famous for its musical venues and figures—was a bandleader and music teacher.

Walter Henri Dyett was born in 1901 in Saint Joseph, Missouri. His mother was a pianist and soprano vocalist, and his father was a pastor in the AME church. Dyett began his musical life as a violinist after his family moved to California; as a student at Pasadena High School, he became concertmaster of the orchestra and also played clarinet, bassoon, and drums. After graduating in 1917, he attended the University of California at Berkeley, where he was first violinist in the school’s symphony orchestra while he completed his premed studies. In 1921 Dyett received a scholarship to the Illinois School of Medicine and moved back to Chicago to pursue his studies. However, his mother and sister, already living there, needed financial help, and he took on work as a musician to support his family. In a curriculum vitae dating from 1960, Dyett described the early days of this work: “One year violinist in Erskine Tate’s Vendome Theatre Orchestra playing the silent pictures and stage presentations along with Louis Armstrong and other now internationally known musicians. Transferred to orchestra leader in the Pickford Theatre—one of the Vendome chain—and remained until talking pictures came in and orchestras went out.” He next became youth music director at a church, then a private teacher of violin and music theory. Finally, in 1931 Dyett began the work for which he would become beloved: he became a music teacher at Phillips High School in Bronzeville. When Phillips was relocated in 1936 and renamed Du Sable High School (after the city’s founder, the Haitian Jean Baptiste Point du Sable), Dyett went along to the new school.

Tribute concerts, memorials, and articles about Dyett often cite his influence on the Bronzeville musical legends who were his students, such as Von Freeman and Nat King Cole. But while these figures loom large in history, they were far outnumbered by the thousands of average Bronzeville teenagers who discovered a love of music through his schoolwide concerts and community initiatives during his thirty-eight years as a teacher.

Dyett was intentional about the pedagogical principles he brought to his work. He explained them in detail in his 1942 master’s thesis for the Chicago Musical College, which explored methods for teaching the fundamentals of rhythm to high school students and argued that music education could help students develop joy and discipline. “The student learns from experience,” Dyett argued, “and these experiences must be enjoyable ones if the proper interest necessary for this learning is to be motivated and sustained.” In another chapter he wrote, “If, in our music classes, we can kindle a spark which will inspire the students to be satisfied with only the best work that they are capable of performing, this development will surely be carried over into whatever field of endeavor they may choose for a vocation.” In a 1969 letter to the musicians’ union celebrating Music Appreciation Week, Dyett echoed the importance of such disciplined determination to do one’s best work: “The world today calls for dreaming possibilities and developing these possibilities into live realities and actualities. Creativity development comes by: becoming receptive to ideas—welcoming new ideas; by being experimental . . . by accepting the opportunity to do more; by asking how can I do more—how can I improve the quality of my performance—how can I do better?”

These principles were to serve as the core of the school that would bear Dyett’s name—a middle school with the motto “develops individuality, encourages responsibility, and provides opportunity.”

When Walter H. Dyett Middle School was dedicated in 1975, the program reflected the scope of Dyett’s influence on his students: Few musicians, living or dead, have brought music into the lives of so many young people and made them a part of the world’s music. ... He was the complete musician: an artist who could teach, a musician’s musician, a student’s inspiration, able tutor, and friend. ... [H]e personally taught or supervised the music education of some 20,000 young people. He brought music appreciation and serious awareness of good music to another half million youth through his activities as a conductor of bands and orchestras in school assemblies and public programs and concerts. ... Dyett was well known for his practice of sharing his baton and podium with promising young musicians and many of them are continuing the “Dyett tradition,” as they enrich school systems in Chicago and elsewhere as music educators, or in the music profession as performers or entertainers.

The decision to name a school after Dyett—a local titan who dedicated his life to young people not on a citywide or national stage but in one specific community, someone who in sharing his passion and his care with generations of students did what all teachers set out to do— appears to be a tacit way of celebrating the community itself. It is a way of saying that a life lived in the service of Bronzeville is a notable life, and that the legacy of someone so dedicated to the community is worth memorializing with something important. Dyett, like many all over the intensely segregated city, was an all-black school, and its daily social happenings took place within what renowned sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois called “the Veil”—the border of an all-black world. In a society that for centuries has drawn absolute boundaries between black people and white people—social boundaries, legal boundaries, economic boundaries, physical boundaries—black social life under conditions of segregation has developed its own reason and rhythm. The Veil, derived as it is from the painful constraints of slavery and Jim Crow and their aftermath, can be cruel. But behind the Veil, Walter H. Dyett, a man whose life could have been seen as ordinary, was honored as a hero.

Reprinted with permission from Ghosts in the Schoolyard, by Eve L. Ewing, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2018 The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Related stories:

CPS Enrollment Drops to 360,000 Students

New Book Examines Government Policies’ Impact on Residential Segregation

New Study Examines Long-Term Impacts of 2013 CPS Closures

New UIC Program Aims to Bring More Men of Color into Classrooms