Among the many things we take for granted in our high-tech era is being able to immediately see what we type on a computer or phone.

But that wasn’t the case for early typewriter users. That is, until a landmark invention by a Chicago-based company changed everything.

Geoffrey Baer explains.

I’m curious to know more about the building on Randolph and Dearborn. It has beautiful typewriter motifs on the facade of the building.

– Jill Stenson, Chicago

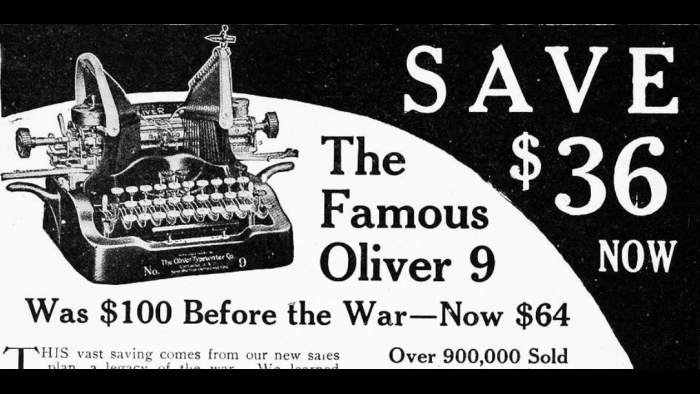

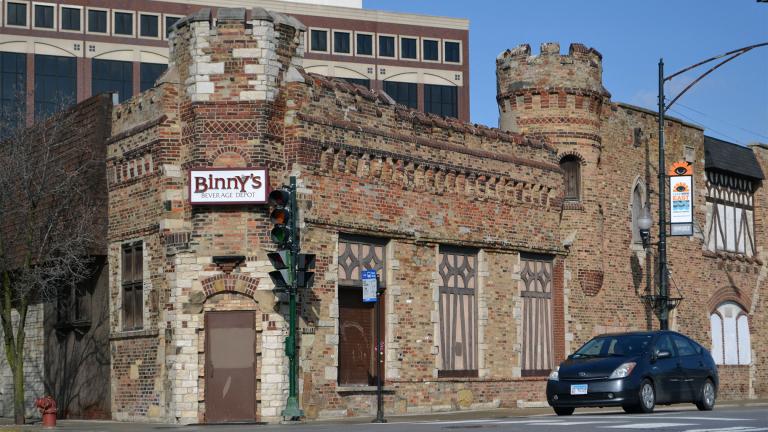

Jill is curious about the old Oliver Typewriter building, once the headquarters of the first company to manufacture a “visible” typewriter. Before Oliver came along in the 1890s, typewriters were “blind” – you had to stop typing and turn a lever to see what you had written!

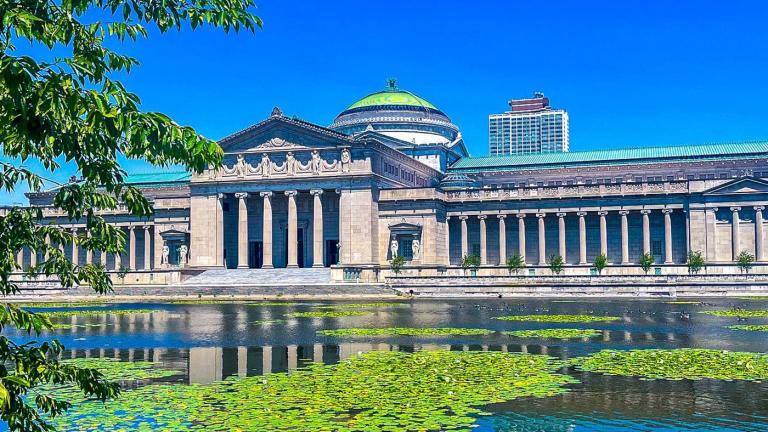

Completed in 1907, the Oliver Building is notable in its own right. Designed by famous architects Holabird and Roche, one thing that stands out is the elaborate ornamentation on its front façade.

The Oliver Building

The Oliver Building

As Jill mentioned, some of the reliefs and carvings point to what was going on inside – like the typewriters interspersed with the company’s logo. You’ll also find eagles, rams and other animals throughout.

Oliver was founded by a minister named Thomas Oliver, who was frustrated by the early “blind” typewriters, which struck the ribbon from underneath the paper.

He invented a U-shaped bar, which acted as a “down strike” onto the typewriter ribbon, allowing typists to – amazingly – see what they were typing in real time!

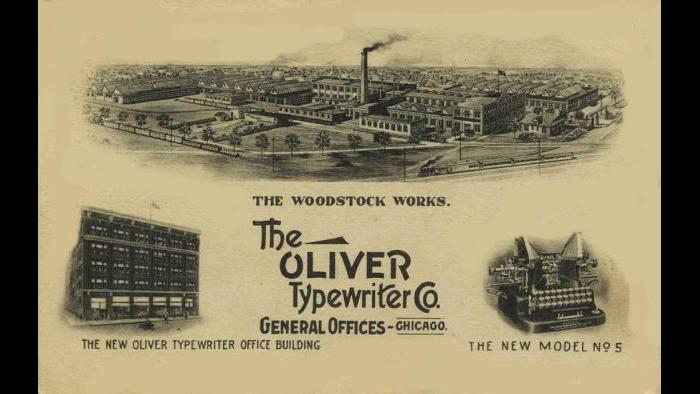

The design proved to be incredibly popular, and in 1896 the company opened a large factory in Woodstock, Illinois.

Office operations were housed in the Oliver Building on North Dearborn. In 1920, two floors were added, again by Holabird and Roche, a staple firm of the Chicago School of architecture.

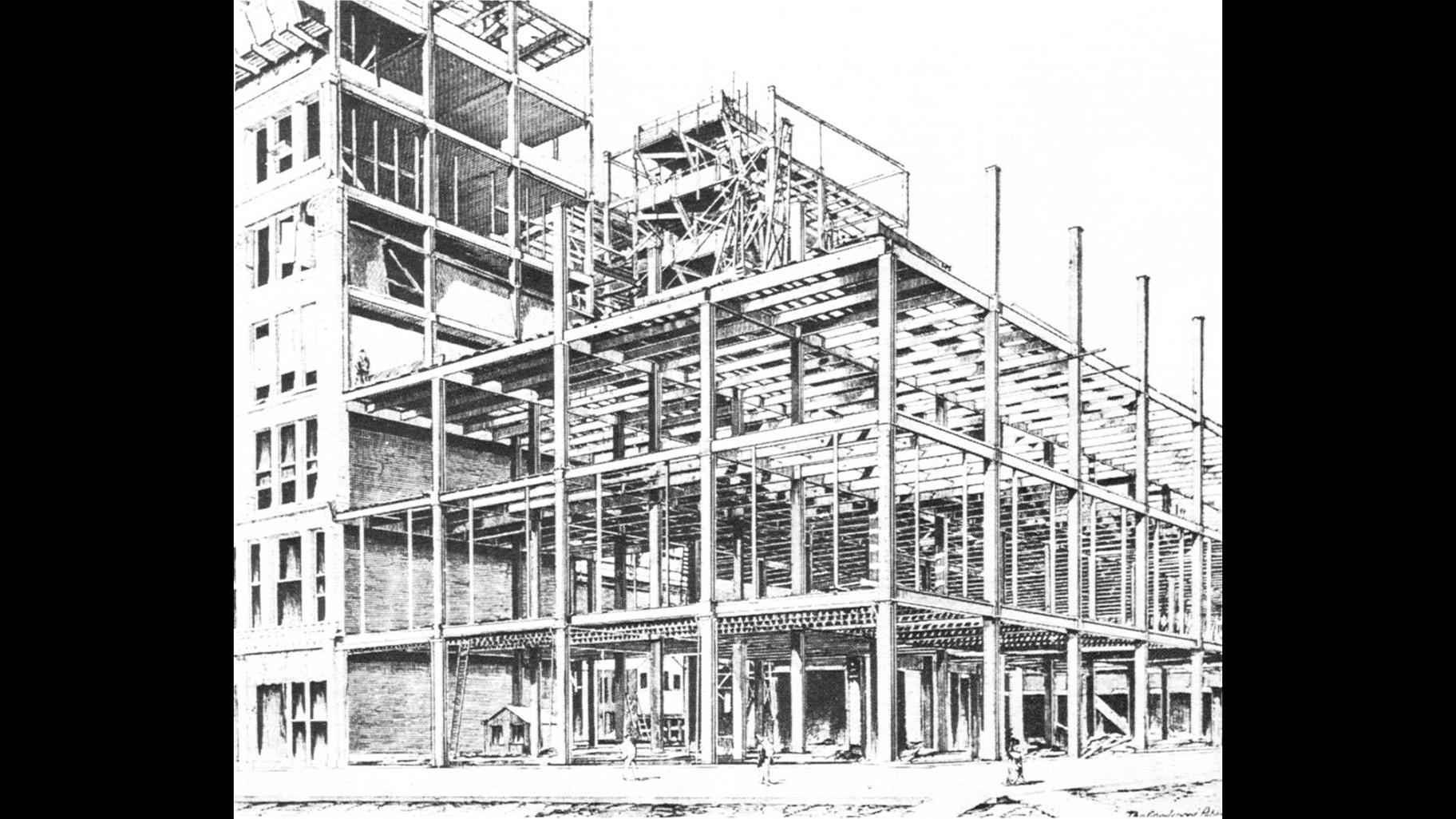

The Chicago School wasn’t actually a school, but a style of architecture. Famous architects like Daniel Burnham and Louis Sullivan were just a few of its adherents.

One key hallmark of the style is steel frame construction, which allowed architects to shift weight off a building’s walls, allowing them to have much larger windows.

The typical Chicago School building windows came to be known simply as the Chicago Window. It consists of a large middle pane designed to let in maximum sunlight. Each center pane is flanked by two smaller windows, which can be opened for ventilation.

You can find these in buildings all over the Loop. Most are much taller than the Oliver Building and emphasize their height in the vertical lines of the gridded facade. One classic example &dnash; also by Holabird and Roche &dnash; is the Marquette Building at Dearborn and Adams. Its Chicago Windows have two large panes in the middle instead of the one.

As for the Oliver Building, it’s had a much longer life than its namesake. Oliver went out of business in the mid-1920s, although the brand lived on for several decades under British ownership.

The building, however, was designated an official Chicago landmark in 1984.

But today, most of what remains is only on the surface. In the late 1990s, it was bought and gutted by the Oriental Theater – now the Nederlander – which expanded its backstage into the building while keeping the façade.

When you pass by today you’ll notice the Broadway in Chicago ads alongside the elegant ornamentation leftover from the Oliver days.

A special thank you to the Made in Chicago Museum and the Rogers Park/West Ridge Historical Society, who lent us their Oliver No. 9 typewriter for this story.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.