Dandelions belong to the same family as dahlias and daisies. So why are they so despised? (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Dandelions belong to the same family as dahlias and daisies. So why are they so despised? (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Housebound Chicagoans have been paying more attention than usual to the seasonal changes taking place in their yards.

Nearly every harbinger of spring has been greeted with a hallelujah chorus — “The birds are chirping!” “The trees are budding!” — with the glaring exception of the dandelion, which could hardly be blamed for wondering why it’s about as popular as a family of bedbugs at a five-star hotel.

“I’m like a little lollipop of sunshine. What’s not to love?” a sentient bloom might ask as it pleads for clemency in the seconds before its head is guillotined by a mower blade.

It’s a fair question. Because it wasn’t always thus.

The dandelion’s fall from grace has been a doozy.

POLL: Dandelions: Yay or nay?

This once-prized plant, which gardeners used to exhibit at county fairs, now holds the title of Public Lawn Enemy No. 1, inciting levels of disgust on par with those directed at vermin, politicians and people who remove their shoes and socks on airplanes.

It’s a reputation, driven by ill-informed public opinion that scientists say is undeserved and ultimately harmful to the planet.

Origin of a Species

We’ll get to the planet in a minute, but first, a bit of botanical background.

The dandelion, technically Taraxacum officinale, is a member of the sprawling Asteraceae family of plants, which encompasses 24,000 to 30,000 species distributed on every continent except Antartica, according to Michael Dillon, curator emeritus of botany at the Field Museum.

Its relatives include chrysanthemums, dahlias, marigolds, zinnias, coneflowers and daisies; once the family connection is made, the similarities are unmistakable. Though the resemblance is less obvious, lettuce and artichokes are also distant cousins of the dandelion.

For centuries, this now-derided plant was treated with the same respect as its widely admired kin, valued as a source of food (and wine), for its medicinal properties and yes, even for its beauty.

Need proof?

Among the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s vast holdings is a rare illuminated medieval manuscript, the “Book of Flower Studies,” by Master of Claude de France, circa 1510-1515. This volume, consisting of portraits of various flowers, provided the blueprint for the garden at The Met Cloisters.

In her curatorial notes, the Met’s Barbara Drake Boehm writes that the book “repeatedly dignifies plants that we today commonly — and wrongly — dismiss as weeds,” placing the “ethereal” and “luminous” dandelion on equal footing with the rose.

“In the hands of the Master of Claude de France, there is no nobler plant than the dandelion,” Drake Boehm writes.

Dandelion, extreme closeup. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Dandelion, extreme closeup. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

In fact, the plant we now attack with herbicidal vengeance was once so highly regarded, early European colonists took great pains to transport it from the Old World to the New.

That’s right: The dandelion was no zebra mussel-style stowaway. It was brought to these shores on purpose, by the Pilgrims, as lore would have it.

“If it serves someone’s fantasy, then yes, the first achenes [which are kind of like seeds, but not] were brought on the Mayflower in a small golden box, and with much ceremony and fanfare, Myles Standish planted them into the virgin soils of eastern North America,” said Dillon, indulging in a bit of fan fiction.

Without a written record, there’s actually no way of knowing the dandelion’s precise origin story in the U.S., but current thought traces its arrival back to the 1600s, Dillon said, when some of the nation’s first European settlers planted it in gardens for use as food and medicine.

Those are the same reasons dandelions are still cultivated today — as in, intentionally grown — primarily in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Poland, he said.

Image Is Everything

Dandelions adapted extremely well to North America, spreading easily, far and wide.

But unlike other unruly imports such as buckthorn or kudzu, the dandelion poses little threat, said Doug Taron, curator of biology and vice president of research and conservation at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum.

People in his line of work worry a lot about invasive species, specifically the aggressive kind that overrun an ecosystem, Taron said, and the dandelion isn’t keeping anyone up at night.

“It’s not a species that displaces natives. They don’t tend to persist if a prairie heals,” he said. “They’re not that much of a problem.”

Not a problem, unless a person isn’t so much concerned with habitat as they are a pristine patch of green turf.

In that case, dandelions are very much a fly in the ointment.

The obsession with lawns dates back to the days when most people were actively involved in agriculture, growing their own food. Lawns were a symbol of wealth, a way to signal that a person could afford to maintain unproductive land, according to Sarah Michehl, community engagement specialist with the Land Conservancy of McHenry County.

The concept took hold and evolved into its current ideal: a uniform, highly manicured swath of nothing but grass.

“It comes down to image,” Michehl said. “It’s this cultural thing. It means that you take pride of ownership in your lawn.”

In this scenario, the dandelion is the unwelcome interloper, not just a blot on perfection but a symbol of neglect and even poverty. Small wonder that people feel compelled to annihilate all trace of Taraxacum officinale, lest they be judged as lazy or lacking in means.

The Park District stopped treating dandelions with pesticides years ago. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Park District stopped treating dandelions with pesticides years ago. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The irony of the lush, green lawn is that for pollinators, a monoculture of grass is the equivalent of a desert. A food desert, that is.

In Chicago, pollinators don’t have a lot of options on which to dine in early spring, a time of year when most native prairie plants are barely poking their heads above ground, said Taron.

Dandelions fill that gap, providing an abundance of nectar. Killing these flowers removes a vital source of food, especially for butterflies, he said.

A movement is afoot to rethink the notion of lawns in the U.S., but whether it takes hold with anything approaching mass acceptance is a giant question mark.

Entities including the Chicago Park District have stopped using pesticides to get rid dandelions, relying instead on mowing techniques to control the plant. (Higher mower settings shade out the blooms.) But these decisions often have more to do with concerns about chemicals than any love of dandelions.

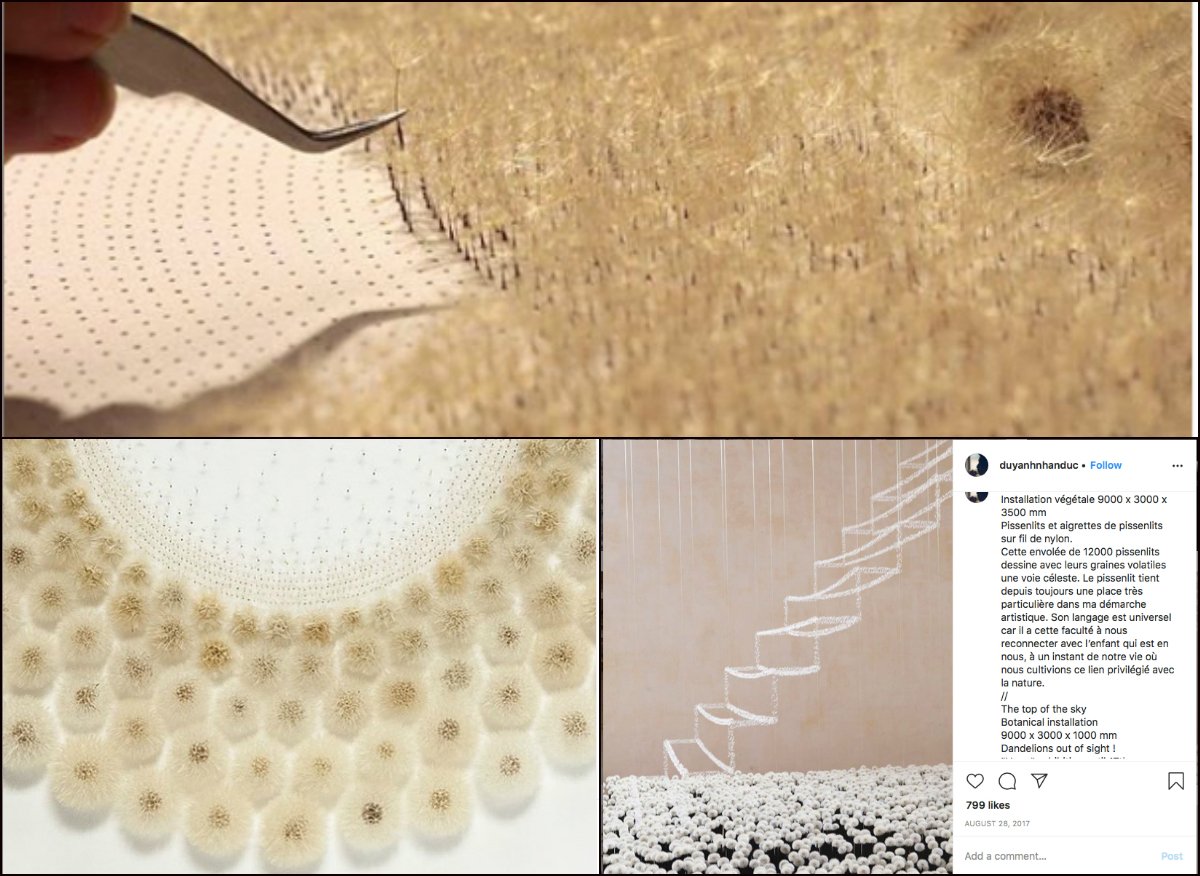

Paris-based botanical artist Duy Anh Nhan Duc creates ethereal sculptures out of dandelions. (Duy Anh Nhan Duc / Instagram)

Paris-based botanical artist Duy Anh Nhan Duc creates ethereal sculptures out of dandelions. (Duy Anh Nhan Duc / Instagram)

What the dandelion really needs is a complete undoing of the past 75 years of wrong-headed thinking, Dillon said.

“They are called ‘weeds’ because they are ‘misplaced plants,’ but if we could rewire a person’s psyche to view them as beautiful, we would be seeing cultural evolution,” he said.

Artists are certainly giving it a try, attempting to reassert the dandelion’s charms, often by playing off the nostalgia for puffballs of childhood wishes.

“Everywhere I look, I see photographs of dandelions, photos of fields of dandelions, with kids, with butterflies, with animals, with their seeds intact, and then fragmenting and blowing away,” said Dillon.

For Paris-based botanical artist Duy Anh Nhan Duc, dandelions are not only a subject but the medium itself. Through a painstakingly elaborate process, he uses individual seed-stems to create everything from sculptures to large-scale installations.

In interviews, he has described their appeal as such: “Under their apparent fragility, they are one of the most skillful and vigorous species in the plant kingdom. They evoke untamed nature, free and wild. The dandelions are ever-present in my work because they fascinate me: the architecture of their seeds arrangement, the lightness and brightness of their feathery tuft and, above all, their ephemeral nature.”

But even with an inundation of positive imagery, Dillon remains dubious the public’s perception of the plant will shift anytime soon.

“I am looking for flying pigs first,” he said. “When we can’t protect the Giant Sequoias, how can we protect a little yellow weed?”

Taron is slightly more hopeful that the dandelion’s reputation can be rehabilitated.

He points to milkweed as an example of another misunderstood, underappreciated plant that has risen in status thanks to its association with the monarch butterfly.

Playing up the dandelion’s importance to pollinators, and by extension the food chain, could be the ticket to the dandelion’s comeback, Taron said.

Dillon has another, timely suggestion: “Perhaps someone can find some anti-viral properties.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]