Young people have often been at the forefront of the fight for racial equity, like in the recent movement sparked by the murder of George Floyd.

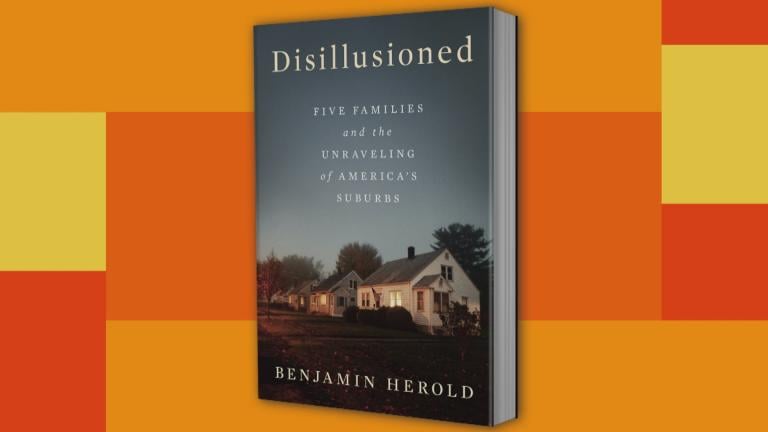

Helping young people figure out how to take a stand against racism is the topic of the latest selection in our Black Voices Book Club Series. “How to Fight Racism: A Guide to Standing Up for Racial Justice” aims to give young people information and tools to fight racism and effect change.

“Every chapter of this book is filled with practical racial justice action steps, everything from interviewing a family member about their past recollections of race or racism growing up to running for student government and getting a taste of what it's like to make policies for large groups of people. There’s something for everyone and it is designed to be practical and to be put into use,” said Jemar Tisby, the book’s author.

Tisby breaks down a model he created called the “ARC” of racial justice, an acronym for awareness, relationships and commitment.

“The arc of racial justice is a framework for thinking about how to enact racial justice. So awareness is everything we need to do to build our knowledge and information about how racism operates,” said Tisby. “Relationships means that this is ultimately about people and we have to form coalitions and partnerships, as well as diverse racial and ethnic relationships across the board. And then lastly, commitment is not simply a commitment to staying the course but to changing laws and policies and systems and the way our entire society operates in such a way that it is more equitable for all people.”

Tisby says his book is ideal for children age 8 and older, but can also be useful for adults.

“This book is filled with stories and examples and illustrations that really try to break down this convoluted concept of race and racism in a manner that young people can understand,” Tisby said. “I think that white parents would really be gravitating towards this book because many of them have been recently catalyzed by current events whether it’s the Black Lives Matter movement or the 2020 uprisings or even just our political landscape. I would also say it’s for Black parents and adults of color as well who of course we have our own lived experiences of race and racism, but we also want to be proactive and intentional about equipping our young people to face what is almost inevitable in their lives, racism, but to also do something about it.”

“How to Fight Racism: A Guide to Standing Up for Racial Justice”

Growing up, I went to a Catholic elementary school, even though I wasn’t Catholic. And in fifth grade, I played basketball, even though I was a terrible basketball player. But I lived just outside of Chicago in the 1990s when the Bulls basketball team was on their NBA championship winning streak and Michael Jordan was on his way to becoming the G.O.A.T. (Greatest Of All Time).

I mean, I wasn’t that into sports compared to my friends, but I definitely had this life-size poster of Jordan (6 feet 6 inches tall) that I got from some car dealership, where you could stand next to it and see how you measured up. I was short. Still am. But back then, everyone wanted to be like Mike. And if you were Black like I was (and still am), there was this expectation that you were good at basketball. But me? In fifth grade, I was always the last one off the bench. The other kid who was my same height, only white instead of Black, was the second-to-last one off the bench.

At the time, I thought it was embarrassing. Black kids are supposed to be good at basketball, but here’s this white kid who’s the same size I am, and he’s better than I am. I felt like I was somehow not Black enough, like I was failing my race or whatever. But mixed in with that was this feeling like, “Why should people expect me to be good just because I’m Black?”

Before I unpack that, however, let me tell you about where I grew up—Waukegan, Illinois. Waukegan is about a forty-five-minute drive from downtown Chicago. It’s a working-class kind of town on the harbor where people made things with their hands, then sent them off somewhere else by boat. The part of town I lived in was full of Black and brown people, mostly Latino. I remember that all the signs downtown were in Spanish, and a lot of the guys I hung out with spoke at least a bit of Spanish, but a lot of them spoke it fluently. Today, some people act like Latino folks are a threat, that immigration is a big scary deal, but back when I was in fifth grade, I thought it was cool that these kids who were my age could speak two languages when I could only speak one.

My dad moved our family to Waukegan just before I was born. He worked at a company that made medicine, managing a team from his cubicle. As far as I know, he was the first of his family to go to college and get an office job like that. All the other people who worked with my dad and did what he did lived in Chicago’s middle-class suburbs, which were mostly white. But my dad made the intentional choice to move farther away from his job to a city where none of his coworkers lived because there were more people of color in Waukegan than in other places. It was a poorer area. People from my dad’s work would invite him over to their houses, but nobody wanted to come to our house because it was in the “dangerous” town. I think he wanted to raise his family in a community like the one he grew up in.

My parents grew up in Michigan, in a segregated neighborhood. It wasn’t like they could have lived anywhere else when they were kids. Back then, there were rules that said Black people weren’t allowed to live next to white people. But I remember my dad talking about how that neighborhood was his whole world, how there was a real sense of community and togetherness there. There were doctors and lawyers and teachers and custodians and plumbers, all Black, all side by side, all supporting each other as best they could. So when he got his cubicle job, he moved us to Waukegan, which was mostly brown and Black people like his neighborhood in Michigan, and life was good.

But back to basketball, which I wasn’t good at, and going to a Catholic school, even though I wasn’t Catholic. The mix of kids in my school looked just like the rest of the population from working-class Waukegan. About half of the kids were Latino, about 20 percent were Black, another 20 percent were white, and the rest were a mix of East Asian and other folks. When I was on the fifth-grade basketball team, our gym was so old that the f loor had all these dents and chips in it, and it had been waxed a million different times and was uneven. We didn’t even have locker rooms. All the boys would have to go into this big custodial closet kind of thing to change clothes. And it was fine because it was all we knew.

It was fine until we started traveling to play basketball against the other Catholic schools in the area. I’ll always remember visiting this one school in another Chicago suburb where most of the people were white, a place my family could have lived because of my dad’s job. We walked in, and their gym had this brand-new rubber floor. I didn’t even know you could have floors made of rubber! And it was huge! It had all these nice things, like actual locker rooms and snazzy logos painted on the wall. It even seemed brighter because all the lights worked and the ceiling was like a mile high.

At that moment, I remember thinking, This isn’t fair. Just because our school is full of Black and brown kids and this school is full of white kids, why do they have all the nice stuff and we have all the broken-down stuff?

Where to Begin

There’s a reason you are reading this book. Maybe you’re going to read it with your family. Maybe you’re in a class and your teacher wants you to understand why the fight against racism is important. Maybe you’ve noticed the contrast between the gym at your school and the gym from the school across town, where the people look different from you. Maybe you’ve seen news stories you don’t understand because they use terms like anti-Black police brutality and white supremacy and racial profiling. (I’ll do my best to explain terms like these in the boxes on the page where they show up, but if you still don’t understand them, you can always ask a grown-up too.) Maybe you already know what those things are and you’re just looking for what you need to do next.

Whatever your reason for reading, my hope is that you’ll come away with a better understanding of where we’ve been as a nation, a deeper knowledge of who you are as a person, a vibrant connection to people of all backgrounds, and a stronger sense of purpose to fix what needs to be fixed in our broken world.

Because our world is broken. Racism is just one of the ways the brokenness comes through. What is racism exactly? I like the definition Beverly Daniel Tatum reaches in her book Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race: racism is a system of oppression based on race.

Let’s break that down a bit. A system is an intentionally organized way of doing something. It isn’t when something randomly happens—it’s making something happen. For example, the public school system was built in a certain way so students would have teachers who report to principals, who report to a superintendent, who reports to a school board, who makes sure that a school is following the laws that were set up by the larger government. It’s organized to run in a certain way.

Oppression is when one person or group of people tries to control another person or group of people. Oppression can take the form of a schoolyard bully, a mean older sibling, or anyone who puts themself in charge when they don’t have a right to be in charge. In each case, the person uses their power and authority to make life harder for other people.

Race is a category you get placed in because of your skin color. Race gives certain groups unfair benefits, and other groups don’t get those benefits just because they’re in a different group.

To say that racism is a system of oppression based on race is to say that things have been organized by people in society to give undeserved authority and advantages to one group of people over another because of the color of their skin. And the sad truth is that racism causes all kinds of problems in the world. So when you say you want to fight racism, the first problem you come up against is, “Where do I start?”

Should we look first at examples of modern racism? Maybe we should start with historical racism like the transatlantic slave trade, lynchings, or the Ku Klux Klan. Should we talk about how Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and said, “All men are created equal” when at the same time he enslaved Black people?

The problem of racism is older than America but as current as today’s headlines. It’s as violent and wrong as a public lynching, but it can dress up in fine clothes to attend church on Sunday. It can seem far removed when discussed in history books, but it’s as personal as being afraid of someone because they look different than you.

With a problem this big, where do you start?

With you.

Right now.

Reading this book.

Learning about racism and its history in this country as well as in your own life. Figuring out how you can make relationships with people who are different from you. Accepting the challenge to change the future.

If the fight against racism seems like a huge responsibility, that’s because it is. But it isn’t bigger than you can handle because you aren’t fighting alone. Change can start to happen when groups of people—big or small—come together and dedicate themselves to fighting racism in all the ways it shows up in the world. And history shows us, and hope needs us to believe, that when people work together, they can find creative solutions to society’s biggest problems.

This fight isn’t just for grown-ups. Some of the greatest advances in the fight against racism have happened because kids fight too.

The Birmingham Children’s Crusade of 1963

During the Civil Rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, Birmingham, Alabama, was an example of racism in action. Segregation in the city made it so Black people were not allowed in certain businesses and only allowed to go to others on “colored days.”

In his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the court. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation.”

Civil rights groups, including King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), planned a series of nonviolent protests to convince Birmingham’s leaders to desegregate the city. Things got worse when a circuit court judge allowed the police to arrest people who protested, demonstrated, or boycotted certain businesses in town.

When the arrests of thousands of adults did little to change people’s minds, SCLC leader James Bevel started planning a “Children’s Crusade.”

Throughout April 1963, thousands of kids were trained in nonviolent tactics. On May 2, those kids gathered at 16th Street Baptist Church before heading into the city to peacefully protest segregation. By that evening, almost one thousand of those kids were arrested. The youngest protester to be arrested was Audrey Faye Hendricks, age nine. Audrey’s family was already involved in the Civil Rights movement.

“Well for me, there was no way not to be involved,” said Audrey in an interview with PBS years later. “My parents were involved from the point that I could remember. My mother was the assistant secretary of the Alabama Christian Movement. My father had gone to jail for riding on the bus. My church was involved. There was just no way around it.”

After one Civil Rights mass meeting, Audrey told her parents she wanted to participate in the protests, knowing she would go to jail. Her parents agreed to let her. Audrey spent a week in juvenile hall at the Birmingham City Jail. She wasn’t allowed to see her family. She had no clean clothes to change into. She didn’t even have a toothbrush. The only blessing of being arrested the first day of the crusade was that she was already behind bars when the racist commissioner of public safety, Bull Connor, ordered police officers to spray kids with powerful water hoses, hit them with batons, and threaten them with police dogs.

In spite of these new dangers, children continued their nonviolent demonstrations over the next few days. By this time, photographers from major news companies were being sent to Birmingham to record the police brutality. These photos and videos were broadcast around the country and led to a national outcry. Birmingham business owners started feeling the pressure to change.

On May 10, just over a week after the Children’s Crusade began, city leaders reached an agreement with Civil Rights leaders to desegregate their businesses and free everyone who had been jailed during the protests.

Birmingham’s racist history didn’t stop with the end of the crusade, but the crusade was the thing that helped convince President John F. Kennedy to pass new Civil Rights laws that could be enforced by the military. In June 1963, he told the nation that the racism happening in Birmingham and elsewhere could no longer be ignored.

In 1964, after President Kennedy was killed, the Civil Rights Act became law in America, making it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Can kids actually fight against racism? Audrey Faye Hendricks did. The thousands of others who stood with her against fire hoses, dogs, and the policemen’s batons did.

You can too.

Excerpted from How to Fight Racism Young Reader’s Edition by Jemar Tisby Copyright ©2022 by Jemar Tisby. Published by Zondervan. Used by permission.