A dual memoir by a Chicago-native U.S. Marine and an Afghan interpreter offers insight into the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan one year later and the Afghans who are still trying to find safety and security.

Following the withdrawal, thousands of Afghans who helped U.S. forces during the war were suddenly stranded and in imminent danger, including Afghan interpreter Zainullah “Zak” Zaki and his family.

“He took great danger to his own life and really fought alongside us,” Major Tom Schueman said about their time together in Afghanistan.

Schueman led his own social media campaign asking for help in getting Zaki and his family out of the country before being discovered by the Taliban. The story gained attention from news media and politicians.

After several separate attempts, Zaki and his family were able to flee Afghanistan and immigrate to the U.S. in 2021.

Schueman has been working with Zaki to help him obtain a visa through the Special Immigrant Visa program, which is aimed at translators or interpreters in Iraq or Afghanistan who worked with U.S. Armed Forces.

However, Schueman described the process as cumbersome with a lot of bureaucratic red tape. Zaki was denied several times already, and is on his final appeal. If he isn’t awarded his visa, he faces deportation.

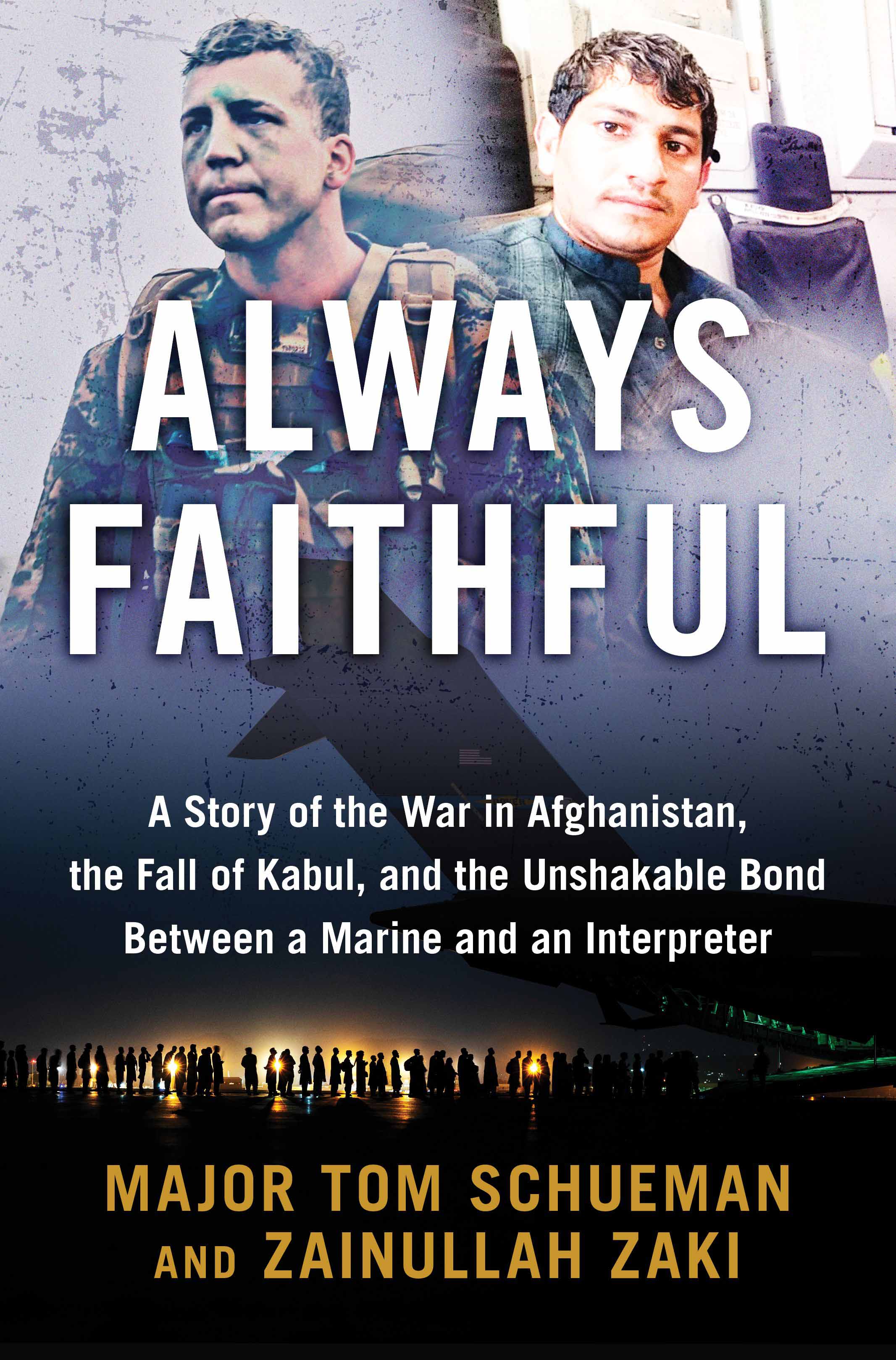

More about their story is in the book, “Always Faithful: A Story of the War in Afghanistan, the Fall of Kabul, and the Unshakable Bond Between a Marine and an Interpreter,” read an excerpt below.

LOOKING AT ZAK, as I departed FOB Inkerman, was like leaving a blood relative and knowing it was likely forever. We had experienced the entirety of the human condition together, had fought together, lost friends together, and laughed at things never considered by the main of humanity. It’s hard to put words to the experience of a combat deployment, especially ones in which accomplishments and benchmarks seemed like sand castles made by excited kids, one moment standing proud, the next crumbling before an inexorable tide. In the absence of clear and sustainable results, the Corps generally falls back on the numbers we call “metrics” as a means of accounting for the outcome of operations. The “metrics” sanitize First Platoon’s seven months of lived reality through a sterile reporting of military events that ignores the radically altered life trajectories of entire families. Between September 2010 and April 2011, I, Zak, and First Platoon lived bloody lifetimes behind the numbers.

First Platoon executed 167 squad-sized patrols and another twenty platoon-sized operations. Three Marines were killed in action under my command. Sixteen, more than a third of us, were wounded by gunfire and explosions. Sometimes that meant a few days of rest; sometimes it meant traumatic amputations and a lifetime of pain. Along the way, we found 102 improvised explosive devices, sometimes by triggering them. We found eighteen weapons caches filled with rocket-propelled Grenade launchers, rockets, rifles, vast quantities of ammunition, and thousands of pounds of homemade explosive and other IED components. In months of daily firefights, we killed seventy-five Taliban, wounded nine, and captured another twenty. Zak put himself and his family at risk of assassination forever, simply by trying to make a better life for the people of Afghanistan. The metrics totaled to equal the fact that I was ready to go home by April 2011 and, even if I wasn’t, it was time. Orders are orders. But I hated to leave a friend to a fate over which I had no influence.

On April 6, 2011, I walked from the helicopter pad at FOB Inkerman to Zak’s room. He didn’t have a door, just a blanket. I slapped my palm against the mud wall outside his door and called for him, “Zak! Hey, Zak!”

He pulled the blanket aside and gave his customary grin. “Lieutenant Tom. I am glad you are not gone to America yet.”

I did not know what to say. What do you say to the man who stood ready to put himself between you and a bullet? How do you say good-bye to someone you love and whom you also know you will likely never see again? How does a warrior say goodbye to a war and the brother he is leaving with it? Every word that came to my mouth seemed inadequate.

“Hey, Zak, I wanted to say thank you. You have been amazing. I will be there for you if you need me someday. These new guys will treat you right. But either way, I just wanted to thank you, brother. Here’s all my points of contact.” I handed him a page torn from my notebook, my phone number and email written upon it.

“It’s all good, Lieutenant Tom. Thank you. You and my brothers in First Platoon, you have done so much for my country. You are my friends. You fought for my country to have a better future. I am proud of you.”

I felt like there were a million things to say, but I had to get to the helicopter landing zone for my ride out with Nikirk and Decker. My gear was already there. We would fly to Camp Leatherneck to meet the rest of the platoon who were already there. Elements of the battalion had already flown to Manas, Kyrgyzstan, and would soon be drinking cold beer in Southern California. We were both silent a moment before Zak said, “You better go before you miss the airplane. I will walk down with you.”

We walked together in silence. There was no need to speak of the moments we had already shared. I was unable to speak about the different futures that awaited us. We reached the landing zone, where an MV-22 Osprey was already landing to take us aboard and fly before the Taliban could fire rockets and mortars at it. The rotor noise was growing as the Osprey settled onto the landing zone. I just needed to pick up my gear and board the bird. I was ready to get home and fix my failures with Andrea, but part of me wanted to stay in Helmand. Part of me always will.

Before I could, Zak had already shouldered my stuffed ruck sack and started walking to the plane. In Helmand’s blistering heat, the Osprey’s prop wash and engine exhaust were even hotter than normal. Under the tail, before turning to walk up the ramp, I reached out and pulled Zak close for a hug. I did not trust myself to speak for a moment.

Still gripping his shoulders, I looked down into his eyes, then leaned in to shout in his ear, “Anything you need, brother. Anything.”

He nodded and smiled. I squeezed his shoulder and fist-bumped him before walking up the ramp, taking a seat on the webbing benches, and turning to see him walking away to the edge of the landing zone.

The Osprey rocked and vibrated as we began to break free of Helmand’s grip. The ungainly plane/helicopter combination gained power and altitude, turning toward Leatherneck as the Osprey’s nacelles rotated forward for flight. On the landing zone, I watched Zak shrink as we flew higher and then disappeared in the dust and shimmering heat of FOB Inkerman. I turned my face forward to take advantage of the slipstream through the cabin to dry the rivulets of sweat coming from under my helmet and thought of what might become of my friend. Perhaps I would be back for another tour, perhaps not. But whatever my distant future held, in the next few days, I would be in America and Zak would still be at war in Helmand. There was no redeployment for him.

My Marines were covered in tattoos. Death Before Dishonor. USMC. Semper Fidelis. Those are fine ideals to live by. They come cheap in tattoo joints all over Oceanside, California. But for Zak, life in Afghanistan really was going to be victory or death. It would be another decade before we realized how true that was.