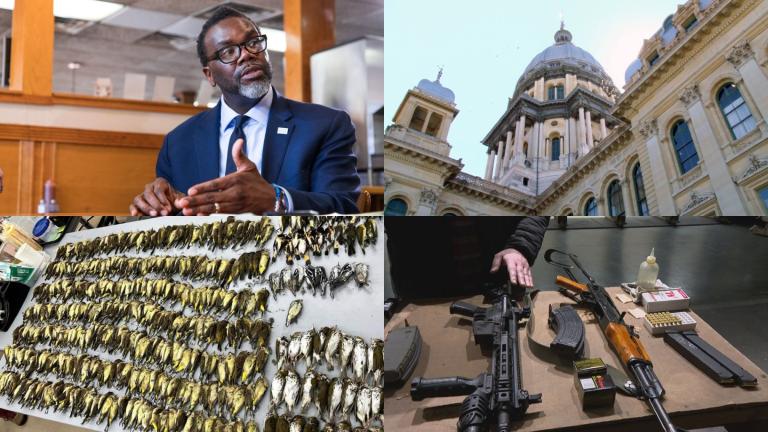

Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson takes questions from the news media after meeting with Mayor Lori Lightfoot on Thursday, April 6. (Heather Cherone/WTTW News)

Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson takes questions from the news media after meeting with Mayor Lori Lightfoot on Thursday, April 6. (Heather Cherone/WTTW News)

When Brandon Johnson is sworn in as Chicago’s 57th mayor on Monday, he will complete a flat-out sprint that started the moment he declared victory on April 4 and vowed to lead the city in a new direction as it struggles to emerge from the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic’s peak while coping with a surge in crime as well as unfulfilled demands for racial justice and economic equity.

Johnson had just 41 days to put together his administration and lay the foundation for an ambitious agenda — the shortest mayoral transition in Chicago history. To complicate matters, that six-week period was studded with difficult moments: unrest on spring’s first warm weekend, the resignation of the city’s interim top cop and fraught negotiations with members of the Chicago City Council.

“It would have been better to have more time,” Johnson told WTTW News Friday. “But we’ll be ready.”

Because of the short transition period, Johnson’s administration will be staffed with holdovers picked by Mayor Lori Lightfoot for at least the first few months, including Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Allison Arwady, whom Johnson vowed to fire during the campaign.

But the decisions Johnson made during the transition offer a glimpse into how he seeks to govern Chicago during a generational shift at Chicago’s City Hall: as an unapologetically progressive politician with a practical streak.

“To deliver the type of transformation we have promised, we are going to have to be effective at delivering services to make good on those promises,” Johnson said, once again vowing to make Chicago a “better, stronger, safer” place to live.

The clearest sign of the mayor-elect’s pragmatic streak was his decision to pick Rich Guidice, the former head of the Office of Emergency Management Communications under Lightfoot and former Mayor Rahm Emanuel, to serve as his chief of staff. That decision won acclaim from many of those who backed Johnson’s defeated rival, Paul Vallas, shortly after they warned Chicago was sure to descend into chaos on the mayor-elect's watch.

Guidice’s appointment came just a few days after unrest swept downtown, ratcheting up fears that the coming summer months would see a spurt of violence downtown that would thwart the city’s uncertain economic recovery from COVID-19 by scaring away wealthy visitors and tourists from the city’s central business district.

Even though Johnson was nearly a month away from taking office, he faced strident demands to take immediate action to stop future incidents.

That anxiety reached a fever pitch after Johnson condemned the violence but said it was “not constructive to demonize youth who have otherwise been starved of opportunities in their own communities.”

Johnson’s remarks represented a sharp break with the typical reaction of elected officials after such incidents. They usually call for a crackdown on teens and young adults who broke the law as well as penalties for their parents — all notes sounded by Lightfoot in her statement.

Johnson has said he is determined to unite Chicagoans around a “holistic” public safety plan that takes a new approach to the surge of crime and violence that began during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and has yet to fully recede.

An Anxious Business Community

Many of the leaders of Chicago’s corporations lined up behind Vallas and contributed millions of dollars to his campaign, only to see him lose. Many worried they would find their access to the corridors of power limited under Johnson, who won after vowing to represent the interests of working-class Chicagoans and is poised to be the most progressive mayor in the city's history.

Johnson also faced concerns that because he has never served as an executive or worked in city government, he would confront a steep learning curve as mayor that the city could ill afford at a moment of crisis. Even though Lightfoot had not held public office before being elected mayor, and Emanuel had spent most of his career as a presidential aide and member of Congress, they did not face similar criticism.

Guidice’s appointment helped allay both concerns, and tamped down the barrage of criticism facing the mayor-elect.

The politically powerful Illinois Restaurant Association praised Guidice’s “strong understanding of the complex issues we face” and said his appointment signaled that Johnson was committed “to prioritizing solutions to some of the most pressing concerns facing our city, including safety and security.”

As the head of Office of Emergency Management Communications, Guidice stood alongside Lightfoot as she raised all but one of the bridges into and out of downtown for the first time in modern Chicago history during the unrest triggered by the police murder of George Floyd during the summer of 2020.

“We certainly learned a lot from that situation, it was certainly challenging times,” Guidice told WTTW News during an April 21 interview after his appointment.

City officials are now prepared with a plan designed to respond to widespread unrest, said Guidice, who also worked for Daley.

“We are in better position to make informed decisions if that was to happen,” Guidice said.

Guidice said the decision to raise the bridges was made at the “last minute,” but did not answer a question about whether he advised Lightfoot to raise the bridges.

Guidice also implemented Lightfoot’s order to encrypt all police communications and delay them for 30 minutes, citing officer and victim safety.

Johnson has vowed to reverse that order. Shortly after joining Johnson’s team, Guidice said he looked forward to discussing the issue with the mayor-elect.

Guidice will work with John Roberson, tapped by Johnson to serve as the city’s chief operating officer. Roberson held more than a half-dozen positions under former Mayor Richard M. Daley, and went on to work for Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, Johnson’s close ally.

Despite Johnson’s pragmatic decisions during the transition, the fears of Chicago’s business community swelled once again after Johnson named SEIU Healthcare Illinois Vice President Jessica Angus to lead his transition, alongside other union officials and prominent progressive political leaders.

And once again, that apprehension faded once Johnson named his transition committees and 11 subcommittees, led by University of Illinois at Chicago Professor Barbara Ransby and Charles Smith, an insurance executive. Several corporate leaders agreed to serve on transition subcommittees, including Michael Fassnacht, the president of World Business Chicago and a close adviser to Lightfoot.

While Guidice’s appointment might have alarmed Chicago’s progressive political community, his reputation as a nonpartisan member of the city staff capable of executing directives and knowledgeable about how to get the city’s massive bureaucracy to move muted those concerns, along with the simultaneous announcement that state Sen. Cristina Pacione-Zayas will serve as Johnson’s first deputy chief of staff. Pacione-Zayas will resign from the Illinois Senate.

A former vice president of the Erikson Institute, Pacione-Zayas helped push state lawmakers to increase funding for education before winning a seat in the Illinois Senate and joining the progressive caucus and becoming a reliable supporter of their initiatives.

Pacione-Zayas’ appointment not only delighted members of Chicago’s progressive political community, but also ensured that one of the mayor’s top aides would be Latina, with an expertise in education — an issue at the top of Johnson’s agenda.

Johnson taught middle school before working as an organizer for the Chicago Teachers Union and serving on the Cook County Board of Commissioners.

Pacione-Zayas said her appointment alongside Guidice is a down payment on Johnson’s campaign promise to create a “Chicago for all.”

“He’s going to be the mayor for everyone, he is going to invite everyone to the table, the different perspectives, and work collaboratively,” Pacione-Zayas said.

But Johnson will have to walk a political tightrope as he works to deliver on that promise without offending or angering the progressive voters who launched him into the runoff and then into the mayor’s office on the fifth floor of City Hall.

Many progressive Chicagoans spent much of Lightfoot’s time in office furious that she failed to support many of their priorities after campaigning on a platform that echoed many of their demands. During the campaign, Johnson accused Lightfoot of “breaking every single promise she made.”

Since his election, Johnson has faced consistent questions from the news media about whether he will reopen the mental health clinics closed by Emanuel, and terminate ShotSpotter’s contract with the city, as he promised.

Johnson told WTTW News he is committed to reopening the city’s publicly run mental health clinics, fully funding Chicago’s schools, making sure Chicago’s public transportation system is clean, safe and efficient and Chicagoans have access to clean water and fresh food.

“I understand those demands for change as evidence that the city’s political system has been a disappointment for some time,” Johnson said, acknowledging that many Chicagoans question whether true change is even achievable.

“I believe it is possible, and I’m going to lead by example,” Johnson said.

Public Safety an Early Focus

Two members of the Chicago Police Department who left during Lightfoot’s administration, also joined Johnson’s transition team: Brendan Deenihan, the former chief of detectives, and Robert Boik, the former head of the department’s Office of Constitutional Policing and Reform.

Johnson tapped a third former member of the Chicago Police Department, who left the Chicago Police Department in July 2020 after serving as its third-highest ranking official, to lead the beleaguered department on an interim basis.

Waller will replace interim Supt. Eric Carter, who will step down on Monday after just two months as Chicago’s top cop. Carter replaced former Supt. David Brown, who quit after Mayor Lori Lightfoot lost her bid for reelection. Johnson had promised to fire Brown.

While Johnson praised Waller as “caring, collaborative and competent,” Waller described his approach to policing as “old school” – alarming advocates for police reform, including journalist Jamie Kalven, who exposed the 2014 police murder of Laquan McDonald.

Senior Staff

With less than a week to go before taking office, Johnson began filling out his senior leadership team by naming S. Mayumi “Umi” Grigsby, as director of policy and Jennifer “Jen” Johnson as his deputy mayor of education, youth and human services. Neither position requires City Council confirmation.

Johnson, a former history teacher at Lincoln Park High School, was Chicago Teachers Union President Stacy Davis Gates’ chief of staff and was on the front lines of the union’s bitter contract fights with Lightfoot. The current teachers’ contract expires in 2024.

In addition, Johnson tapped Jill Jaworski, managing director and partner at PFM Financial Advisors, as the city’s chief financial officer. Jaworski, whose appointment must be confirmed by the City Council, would replace Jennie Huang Bennett, who Lightfoot has credited with putting the city on firm financial footing despite the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic and the city’s massive pension debt.

Johnson also selected Annette C.M. Guzman to serve as budget director. Guzman, who also must be confirmed by the City Council, served as Cook County’s budget director, reporting to Preckwinkle.

Johnson Puts Stamp on City Council Reorganization

The mayor-elect also spent considerable time negotiating with powerful members of the Chicago City Council and convinced them to step back from a declaration of independence made five days before he defeated Vallas.

That plan, approved over the opposition of two leading organizations championing government reform, called for the creation of nine new committees for a total of 28 committees, likely costing the city $8.4 million.

Instead, Johnson on Friday announced a City Council organizational plan that will create just one new committee for a total of 20 committees. The new plan also sees the ouster of several Lightfoot allies who were hoping to keep their plum positions of power as committee chairs that come with an average budget of approximately $300,000.

Whether the City Council continues to assert its independence after Johnson takes office is an open question, even though he has backed an effort to transform it into a legislative body responsible for setting policy for the entire city and not a rubber stamp.

Johnson touted his City Council reorganization proposal as a “unity plan” that “will align the mayor's office and City Council around shared values and priorities.” It must be ratified by the City Council at its first regular meeting after the inauguration, which is set for May 24.

The flexible budgets of City Council committees have long been a coveted perk for some of Chicago’s most powerful politicians, allowing them to hire political supporters without running afoul of rules that normally prohibit coveted jobs from being awarded to friends and, in some cases, family members.

Ald. Scott Waguespack (32nd Ward) lost his powerful perch as Finance Committee chair after publicly warning Johnson not to attempt to change the plan approved by the City Council.

“I was a little bit disappointed, but the mayor has an opposite direction he wants to go,” Waguespack told WTTW News. “We’re gonna work to make sure the city moves forward despite not having that position.”

Waguespack will be replaced by Ald. Pat Dowell (3rd Ward), who endorsed Johnson on Feb. 3, giving his campaign a much-needed endorsement from a moderate member of the City Council’s Black Caucus. Dowell had also been a close ally of Lightfoot, serving as her budget chair for four years.

Ald. Jason Ervin (28th Ward), who endorsed Johnson in the runoff after backing Lightfoot, will become chair of the Budget Committee.

Ald. Michelle Harris (8th Ward) will remain as chair of the Rules Committee, even after backing first Lightfoot and then Vallas, only to see Johnson win an overwhelming majority of votes in her South Side ward. Harris also served as Lightfoot’s floor leader.

Ald. Carlos Ramirez Rosa (35th Ward) will not only lead the powerful Zoning Committee but also serve as Johnson’s floor leader, making him the most powerful member of the City Council. That represents a remarkable rise to prominence for Ramirez Rosa, who was just 26 years old when he defeated a powerful incumbent politician tied to the City Council’s Democratic machine in 2015, and was once the only Democratic Socialist on the Chicago City Council.

On Monday, seven Democratic Socialists will be sworn into office, including Ald.-elect Angela Clay, who will represent the 46th Ward, which includes Uptown.

Including Ramirez Rosa, five Democratic Socialist members of the City Council are set to lead committees starting in May, a massive expansion of their power at City Hall. Under Lightfoot, no members of the Democratic Socialist Caucus served as committee chairs.

Eleven of the 20 committees will be led by City Council members who endorsed Johnson.

Ald. Brian Hopkins (2nd Ward), a prominent supporter of Vallas, will lead the City Council’s Public Safety Committee.

But others who backed Vallas, including Ald. Walter Burnett (27th Ward), will find themselves on the outside looking in. Burnett, who has led a committee since Daley was mayor, will now serve as vice mayor, a ceremonial position with no real power – or budget.

Tense relationship with Lightfoot

Even as Johnson worked to set up an administration in approximately six weeks, he faced escalating tensions with Lightfoot, who leaves office as the first mayor not to win a second term since 1983; the second woman to serve as Chicago’s mayor following in the footsteps of its first, Jane Byrne.

Lightfoot’s frustration over her loss appeared to boil over during an appearance on MSNBC’s Morning Joe program on Monday, when she incorrectly described Johnson as a Democratic Socialist and slammed Vallas as a member of the GOP.

“Unfortunately, the people who are jumping on the bandwagon of a Republican posing like a Democrat now got a Democratic Socialist as the mayor,” Lightfoot said. “So, careful what you wish for.”

The day after that interview, Lightfoot declared a state of emergency, with the city’s shelters at capacity and officials amid an escalating humanitarian crisis caused by a surge of migrants from the southern border.

Despite her status as a lame duck, Lightfoot did not hesitate to exercise her power as mayor by signing 14 executive orders after her defeat, including 11 on Friday, her last full weekday in office.

Johnson told WTTW News he would review each order signed by Lightfoot, and decide whether to revoke them.

“Chicago has a tremendous opportunity to unite around the values I ran on, and that’s what I’m focused on,” Johnson said, dismissing a question about whether he thought Lightfoot’s actions were aimed at kneecapping his administration before it started.

“She is well within her rights to exercise her authority,” Johnson said.

In four years, Lightfoot signed 27 executive orders, while Emanuel signed 21 executive orders during the eight years he was mayor of Chicago.

And after a slew of appointments were blocked from advancing through the City Council by Ald. Anthony Beale (9th Ward), Lightfoot selected Kevin Barszcz to lead a re-established Office of Veterans Affairs.

By comparison, the last executive order issued by Emanuel came in January – more than a month before the election.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]