Lake Michigan, at a high-water mark in 2019. (WTTW News)

Lake Michigan, at a high-water mark in 2019. (WTTW News)

As an expert in hydrological modeling, Drew Gronewald is in the business of predicting the seemingly unpredictable.

Among his focus areas is one of keen interest to Chicagoans: the forecast for Great Lakes water levels.

On Friday, Gronewald, an associate professor with the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan, delivered his annual presentation on the current state of Great Lakes water levels, and the good news is, that in the near term, Lake Michigan is holding fairly stable.

After a couple years of record highs, followed by a marked dip, Lake Michigan-Huron in 2023 is relatively unchanged from 2022. Looking ahead another 12 months, Gronewald said the lake appears likely to maintain that middle-of-the-road pattern.

But for how long?

In the past, it was widely accepted that the Great Lakes experienced long-term cycles of highs and lows, “but over the past 20 years, if that cycle existed, it’s broken,” Gronewald said.

Factors affecting lake levels — what Gronewald terms “net basin supply” — include precipitation (be it rain or snow), evaporation and run-off. And precipitation and evaporation are currently in a tug of war.

These two competing forces — one dumping water into the basin and the other whisking away moisture — are increasing in intensity, and occasionally one gets the upper hand, he explained.

When that happens, the result can be an extreme swing in water levels. The question for hydrologists like Gronewald is whether the increased intensity will lead to even higher high-water marks or lower low levels.

Computer simulations may provide clues, but there’s one variable that defies the combined brain power of humans and machines, he said. And that’s timing.

“We’re not sure when those extremes are going to happen,” he said. “Will it be in 40 years or five years?”

Gronewald’s complete presentation, along with a Q&A session hosted by the Environmental Law and Policy Center, can be viewed online.

Here’s what else caught our attention this week.

CLIMATE: We’ll See You in Court

Glacier National Park's Grinnell Valley. A group of Montana youth are suing the state for violating their constitutional right to a "clean and healthful environment." (National Park Service / Tim Rains)

Glacier National Park's Grinnell Valley. A group of Montana youth are suing the state for violating their constitutional right to a "clean and healthful environment." (National Park Service / Tim Rains)

Montana’s constitution guarantees its citizens the right to a “clean and healthful environment,” and a group of young Montanans is holding the state to its word.

In a landmark environmental trial now underway, the youth have taken the state to court, claiming its failure to address climate change — by promoting and permitting the fossil fuel industry — has violated their rights.

The plaintiffs include teens who live near Glacier National Park, which has lost 70% of its glacial ice since the mid-1900s. The Flathead Beacon (a local media outlet) is following the trial, which is expected to last two weeks.

RESEARCH: Saturn Moon Shows Signs of Life

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft spectacularly crashed and burned into Saturn in 2017 after orbiting the ringed planet for more than 13 years, but the data it collected lives on and just produced an astounding discovery.

Scientists dug deep into samples gathered by Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer, which sounds like an invention straight from “The Jetsons” but is in fact NASA-designed-and-named technology.

What they found was evidence of phosphorus — a key building block for life — present in icy particles spewed from Enceladus, one of Saturn’s moons.

“It’s the first time this essential element has been discovered in an ocean beyond Earth,” said Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, who led the new study.

Further experiments showed Enceladus’ icy ocean might contain concentrations of phosphorus 100 times greater than what’s found on Earth.

Next up for NASA: The Europa Clipper is set to launch in 2024, speeding toward Jupiter and its similarly icy moons. Will they hold phosphorus, too?

And if they do, given the state of our own planet’s dwindling phosphorus supplies, how soon before the search for other life in the universe becomes a mining mission?

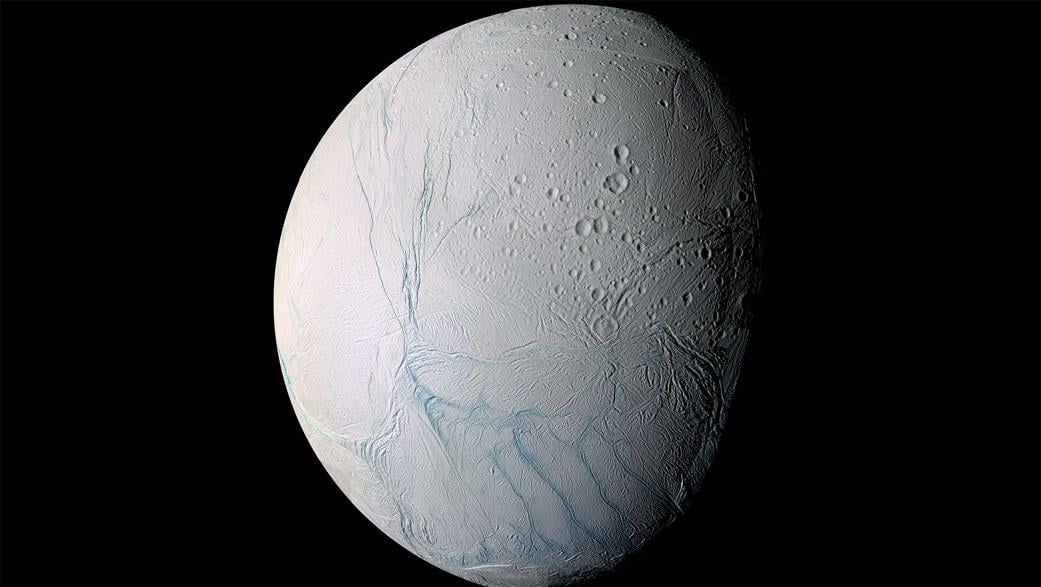

During a 2005 flyby, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft took high-resolution images of Enceladus that were combined into this mosaic, which shows the long fissures at the moon’s south pole that allow water from the subsurface ocean to escape into space. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

During a 2005 flyby, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft took high-resolution images of Enceladus that were combined into this mosaic, which shows the long fissures at the moon’s south pole that allow water from the subsurface ocean to escape into space. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

ECOSYSTEMS: In Defense of Grasslands

Maybe you’ve heard of movements to plant a billion, or even a trillion, trees worldwide to replenish forests and their carbon-storing capability as earthlings look for ways to stave off the worst impacts of climate change.

But there’s a place in Missouri where conservationists chopped down 19 acres of trees in order to save a grassland.

In an opinion essay in the New York Times, “When Chopping Down Trees Is a Gift to the Environment,” eco-restorationist Robert Langellier presents a passionate argument for the preservation of grasslands, particularly in the South and Southeast, where it’s long been incorrectly assumed that forests are and always have been king.

“Pound for pound, Southeastern grasslands are far more biodiverse than the massive tallgrass prairie in the Midwest or the shortgrass prairie of the Great Plains,” Langellier writes.

They’re just waiting for someone to let in the sun.

WILDLIFE: Where the Wildcats Roam

The Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris), dubbed “rarer than a tiger,” is getting a new lease on life.

Scotland has just released a group of captive-reared wildcats into the country’s Highlands as part of a program to revive this nearly extinct native species. Population declines due to habitat loss and hunting, as well as interbreeding with domestic felines, have led to the wildcat’s listing as “critically endangered.”

Lest the comparison to tigers suggest that the Scots have unleashed a fierce predator destined to terrorize unsuspecting tourists on distillery-hopping vacations, it should be noted that the Scottish wildcat is the size of a husky kitty cat.

Tweet of the Week

Breaking news: You can now fritter away the day watching bears fish for salmon.

Returning for an 11th season, the world-famous bear cam livestream at Katmai National Park in Alaska begins today. The bear cams go live at 8 a.m. Alaska Daylight Time, or 11 a.m. CDT.

Livestream: https://t.co/4nJUmY0UNk

National Park Service. https://t.co/PFi2fGSugU. pic.twitter.com/HhRbsPCwAC

— EarthSky (@earthskyscience) June 16, 2023

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]