Video: The WTTW News Spotlight Politics team breaks down the day’s biggest headlines. (Produced by Alexandra Silets)

For nearly three and a half years, Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Dr. Allison Arwady spent at least an hour in front of livestreaming cameras in a makeshift studio at City Hall every week, fielding question after question about COVID-19 as it upended the lives of Chicagoans.

But on Tuesday, Chicago residents concerned about a late summer uptick in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations who tuned into the regular weekly question-and-answer session found a terse message: “#AskDrArwady has been canceled.”

During his campaign for mayor, Brandon Johnson promised to fire Arwady, an expert in infectious diseases with degrees from Harvard, Yale and Columbia universities, saying they had different views of public health.

On Friday night, he did just that, nearly three months after taking office, setting off a wave of recriminations and outrage that served to increase pressure on his administration to deliver on his vision of public health for Chicago — while coping with the continuing pandemic.

Arwady took to social media to announce her dismissal, saying she was “especially disappointed not to get a chance to say goodbye” to her team that helped lead the city during the COVID-19 pandemic that has killed at least 8,160 Chicagoans and hospitalized more than 53,000 since March 2020.

“Public health must always be driven by science and medicine, and never politics,” Arwady said in a statement posted to X, the platform once known as Twitter.

The editorial boards of both the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Sun-Times blasted Johnson’s decision to terminate Arwady without meeting with her — or without letting her say farewell to Chicagoans who came to rely on her calm, authoritative demeanor during the pandemic’s darkest days.

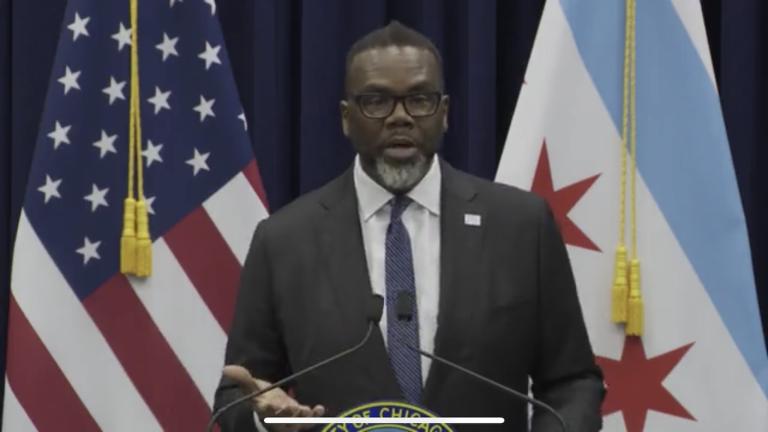

That indignation cast a shadow over Johnson’s introduction of Larry Snelling, his pick to lead the Chicago Police Department — prompting a visibly annoyed mayor to deflect questions about Arwady’s termination.

“Transition is difficult for everyone,” Johnson said at a Monday news conference before quoting rapper Tupac Shakur: “Real eyes, Realize, Real Lies.”

Johnson did not elaborate, nor did he respond to a question about whether he terminated Arwady at the request of the Chicago Teachers Union, who clashed with her and former Mayor Lori Lightfoot about whether to reopen schools in fall and winter 2020.

In a statement, Lightfoot called Arwady a “hero.”

“We all owe a debt to her unflagging commitment to data, science and keeping us all safe through one of the worst pandemics that the world has ever seen,” Lightfoot said.

In an interview with NBC5-TV, Arwady said she did not know whether she was fired because she pushed to reopen schools at a time when leaders of the Chicago Teachers Union believed that would put the lives of students, parents and teachers at risk because the virus was circulating unchecked when vaccines were not widely available.

“I told my colleagues around the country that, you know, at the end of the day, I’m actually a little bit proud to now have joined the ranks of the hundreds of public health leaders who ultimately lost their jobs for making data-driven decisions during COVID,” Arwady said.

A spokesperson for Arwady did not respond to WTTW News’ interview request on Tuesday.

Fikirte Wagaw, who served as Arwady’s deputy, is now acting commissioner.

Mental Health at Center of Mayor’s Race

Long before COVID-19 swept Chicago, Arwady and Lightfoot had been at loggerheads with the city’s progressive political movement that powered Johnson’s victory in April’s mayoral runoff.

Lightfoot’s decision to break her 2019 campaign promise to reopen the public mental health clinics closed by former Mayor Rahm Emanuel delayed and nearly derailed Arwady’s confirmation by the City Council. Her expertise as an epidemiologist never came up during those contentious hearings, nor did the possibility of a pandemic.

Using her considerable authority as a medical expert, Arwady backed Lightfoot’s effort to fill what both acknowledged were “significant gaps” in Chicago’s mental health care system by turning to nonprofit organizations. Progressive leaders blasted that effort as insufficient and ineffective.

During the campaign, Lightfoot relied on Arwady to make the case for that approach, even as Lightfoot’s refusal to reopen the mental health clinics became a rallying cry for progressive candidates and groups determined to deny her a second term.

While most public heath commissioners play no role in elections, Arwady did not hesitate to defend Lightfoot and urge her reelection, even publishing an opinion column in the Chicago Sun-Times.

“Not to be political, but this mayor has been our mental health mayor,” Arwady told WTTW News during an hour-long interview in late January. “I’m hopeful that she will be reelected.”

Arwady also waded into the debate over the proposal known as “Treatment Not Trauma,” which calls for the Chicago Police Department’s $1.94 billion budget to be reduced to fund the reopening of the public mental health clinics and establish a citywide program that would send emergency medical technicians and mental health professionals to calls for help from those in crisis, not armed law enforcement officers.

Lightfoot dismissed that proposal as an effort to “defund the police,” and Arwady told WTTW News Treatment Not Trauma was just a “buzzword.”

Both Arwady and Lightfoot opposed efforts by progressive members of the City Council to fund alternate-response efforts to respond to 911 calls without a police officer — a proposal fully embraced by Johnson as well as Ald. Rossana Rodriguez Sanchez (33rd Ward), the chair of the City Council’s Health Committee.

New Era for Chicago Department of Public Health

Whoever Johnson taps to replace Arwady will not only have to implement his public health agenda by overseeing the reopening of at least some public mental health clinics and the expansion of the alternate response program, but also lead the city through the next phase of the COVID-19 pandemic — along with whatever threat to public health has yet to emerge.

The department’s next leader also faces a looming budget crunch.

Lightfoot and Arwady oversaw a massive expansion of Chicago’s mental health care system under Emanuel and former Mayor Richard M. Daley, when the publicly run clinics served no more than 6,000 Chicagoans per year, according to city data. In 2010, the city spent $13 million annually on mental health treatment.

Chicago nonprofits — funded by a combination of city, county, state and federal tax dollars — and other programs treated more than 61,000 Chicagoans for a variety of mental health conditions, according to estimates released by city health officials.

Chicago’s 2023 budget set aside $89 million to provide mental health care. That includes efforts to treat people outside clinics and other medical facilities, sending clinicians to homeless shelters, on the CTA and in encampments of unhoused people.

Part of that funding came from COVID-19 relief packages from the state and federal governments, and will not be available beyond 2024.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]