Paul Fehribach wants you to take Midwestern food seriously.

Sure – you can rag on our region for Crock Pot meals loaded with cream of mushroom soup, or salads mostly made of marshmallows and Cool Whip. But Fehribach says the culinary depth and national influence the Midwest has had on America’s taste is underestimated.

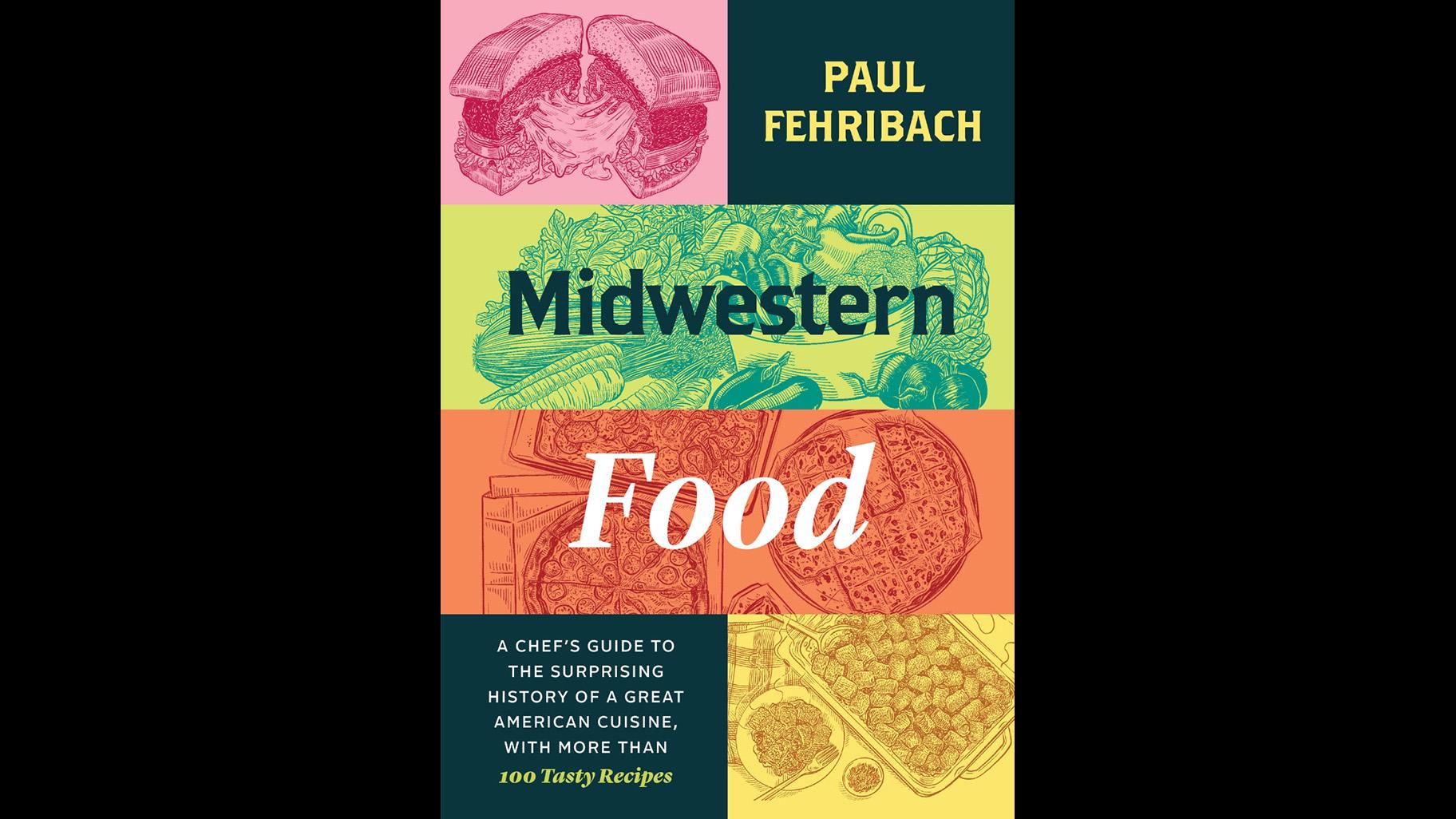

Fehribach, the chef and co-owner of the Cajun restaurant Big Jones in Andersonville, is the author of the new book “Midwestern Food: A Chef’s Guide to the Surprising History of a Great American Cuisine.” His second cookbook, it’s as much a collection of recipes as it is a tour through our region’s food history.

While he mostly cooks up Cajun these days, Fehribach’s earliest culinary memories aren’t from Louisiana – they’re from Indiana.

“My grandparents’ house on their old farm, and where the dairy cow was, and where the smokehouse was, and where the blackberry patch was,” Fehribach said. “They still did hog killings. Grandma had the garden and canned all of these things, and I’d just never seen anything like it.”

When he was traveling around the South learning the cuisine he now cooks for a living, he was impressed by the array of regional foods. And when he went home to visit his folks, “I started to realize, hey, actually we have a lot of cool and interesting regional foods here that when I was growing up, I just took for granted.”

“I wanted to kind of write down and document a lot of those traditional foods, because foodways change and they disappear,” he said.

By celebrating these recipes in his new book, he also wanted to dispel some of the small-minded views people might have of Midwestern cooking.

“It’s derided as meat and potatoes, ranch dressing – which we all love, but there’s a lot more to it than that,” he said.

In the book, Fehribach writes that “throughout our history, the Midwest has been the most consequential region in the development of American food and drink culture.”

“I can’t even really possibly go into depth about why it’s so important,” Fehribach said. “The Midwest has been sort of the industrial hub of the country, that was how it developed. It’s been the bread basket for the country as well.”

Think the meatpackers of Chicago and the flour millers of Minnesota. But the Midwest wasn’t just making food, it was influencing how people cooked.

The character of Betty Crocker was created by the Minnesota-based company that became General Mills.

“Betty Crocker … had more listeners in the South for her radio program, actually, than she did even in the Midwest,” he said.

Cookbooks were a huge part of Fehribach’s research, particularly community cookbooks, and many of them in German brought by immigrants to the Midwest.

Among his finds: “the oldest hamburger recipe that anybody is going to know of to date. The oldest fried chicken recipe.”

That’s right. Fehribach says fried chicken is Midwestern, not Southern. Fehribach also says all-beef hot dogs were invented by Chicago’s Jewish community.

“Sorry, New York. Nathan’s didn’t invent the all-beef hot dog. It was actually decades earlier,” he said.

“Midwestern Food: A Chef’s Guide to the Surprising History of a Great American Cuisine” by Paul Fehribach.

“Midwestern Food: A Chef’s Guide to the Surprising History of a Great American Cuisine” by Paul Fehribach.

Fehribach says that while fried chicken isn’t southern, a lot of Midwestern cooking is shaped by patterns from the Great Migration, with Black Americans from the Delta resettling up north as meat processing was taking off.

James P. Lemon – founder of Lem’s Bar-B-Q – saw meat packers cutting the tips off of spare ribs and put them to use for his Chicago style barbecue, like the kind Fehribach cooked up the morning of our visit.

“Most barbecue you’re doing low and slow,” he said, standing over the grill at Big Jones. “Chicago style, we’re doing a little bit higher of heat, and for not as long.”

Fehribach basted the rib tip and sausage link with a Chicago-style barbecue sauce, “which is similar to Memphis. Again, there’s that connection – family recipes traveling up and down the Delta region.”

There are also multiple profiles of chefs across the region. Fehribach hopes to highlight the foodways of people of color in his book. He says it’s time Black, Latino and Indigenous Midwesterns get their due in the world of food and beyond.

“We need to invite them to the table … and support what they’re doing, because we’re all going to be richer by having them as part of our community,” he said.

A community that Fehribach hopes starts getting louder about its contributions.

“We in the Midwest maybe need to think about tooting our horn a little bit and puffing our chests up and having a little bit of pride about what we’ve done for the country and what the country eats,” he said.

“Midwestern Food: A Chef’s Guide to the Surprising History of a Great American Cuisine” is available Sept. 20.

Contact Nick Blumberg: [email protected] | (773) 509-5434 | @ndblumberg