(Credit: Cottonbro Studio via Pexels)

(Credit: Cottonbro Studio via Pexels)

Illinois’ so-called ban on book bans has gone into effect, but it’s also left those involved in prison education programs curious as to how exactly it’ll impact facility libraries.

The week-old law requires libraries to follow the American Library Association’s Library Bill of Rights in order to be eligible for state funding. That declaration indicates that materials shouldn’t be “proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

The law comes in response to a rising number of book challenges across the country at schools and public libraries.

The Illinois secretary of state’s office, which oversees a number of library grant programs, said the new law does apply to prison libraries as they are eligible for grants. Correctional facilities will retain the ability to determine which items are to be added to their library collections and may choose not to include books that are deemed explicitly instructional to creating a weapon or poison, or other activities that cause physical harm, the office added.

When the Illinois Department of Corrections was asked if this new law changed its criteria on why a book would be disapproved, officials said the department already “does not ban books or resources due to partisan or personal disapproval” and pointed to its publication policy — guidelines that some advocates say can be too sweeping.

That policy states publications can be disapproved for a variety of reasons, ranging from “overtly advocating or encouraging violence, hatred or group disruption” to being “detrimental to the safety, security or good order of the facility.”

“Their guidelines for what is and isn’t admissible are extremely broad,” said Alan Mills, executive director of the Uptown People’s Law Center.

For example, up until recently, “Blood in the Water” by Heather Ann Thompson, a book detailing the Attica prison uprising of 1971 and its aftermath, was not allowed in all Illinois prisons, according to Mills. The law center filed a lawsuit against IDOC alleging a violation of rights; the department settled in September.

The book is now approved by the department.

“Some things are obvious. ... If there was a lock-picking 101 book, I understand that shouldn’t get into prison,” Mills said. “But something about (the Attica Uprising), which happened 50 years ago in an entirely different prison, it doesn’t pose any current, at least obvious, security problem.”

Official libraries are not the only way those in prison gain access to books, however.

These prison guidelines also extend to books being sent into facilities for a person’s personal use.

For Becca Greenstein, a volunteer and board member with Chicago Books to Women in Prison, navigating the guidelines can be frustrating.

The organization sends books to incarcerated women nationwide — and in Illinois alone that’s more than 1,000 per year. The highly requested title “Trans Bodies, Trans Selves” from Oxford University Press is both rejected and accepted by some prisons, Greenstein said.

“It’s really hard to know,” Greenstein said. “Being at their mercy can be stressful.”

And in a large-scale example, more than 200 books were taken off the shelves in Danville Correctional Center’s prison education wing with the Education Justice Project (EJP) in 2019. Among the removed books were “Up From Slavery” by Booker T. Washington and a book by philosopher Cornel West.

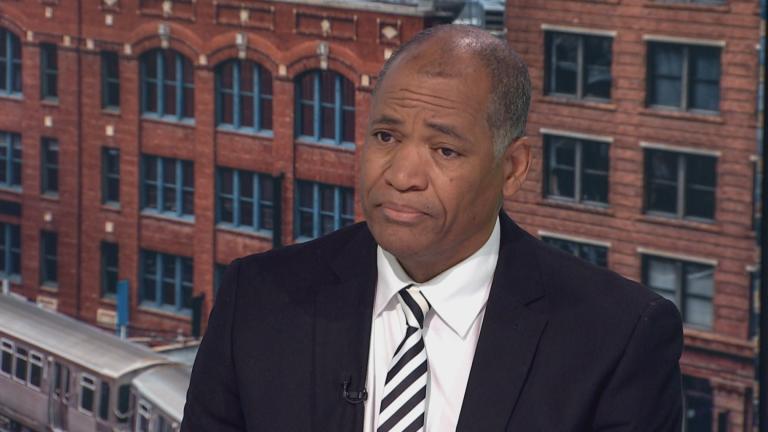

For Michael Harrell, who was incarcerated at Danville and an EJP participant at the time of this removal, it was disparaging.

“It was confirmation of something being done,” Harrell said. “When something is restricted or taken, it must mean that there’s immense power, information in that particular thing.”

Generally, books that deal with the Civil Rights Movement or criticisms of mass incarceration have been censored, Mills said. He’s also seen prison legal news publications be censored, because “as defendant experts put it, it makes prison officials look bad.”

This focus on tying the banning of books to grant funding comes as the secretary of state’s office announced that it is awarding $420,000 in grants to state prison libraries — the most significant public funding toward book purchasing in about 20 years. Twenty-eight libraries will receive $15,000 each to purchase reading materials or library supplies.

In 2017, IDOC spent a mere $276 on books for its educational programming across 28 facilities, according to an Illinois Public Media investigation.

Funding has largely run dry due to IDOC taking authority over the libraries from the secretary of state’s office in 1989. While under the state’s library system, there was much more funding and resources, said Ashton Hoselton, policy and research director with the EJP.

While the fight for sufficient funding continues, having access to reading materials stays vital to incarcerated people.

Edmund Buck, another EJP alumnus, said that while incarcerated he gravitated toward poetry from Gwendolyn Brooks and Maya Angelou, being particularly moved by pieces addressing hope, forgiveness and healing. So much so that he started writing his own poetry — and now is a program specialist for Reading Between the Lines, a literary-focused reentry program.

“If working under the premise of knowledge being power and knowledge aiding my own personal growth, I always felt strongly about having access to material,” Buck said.