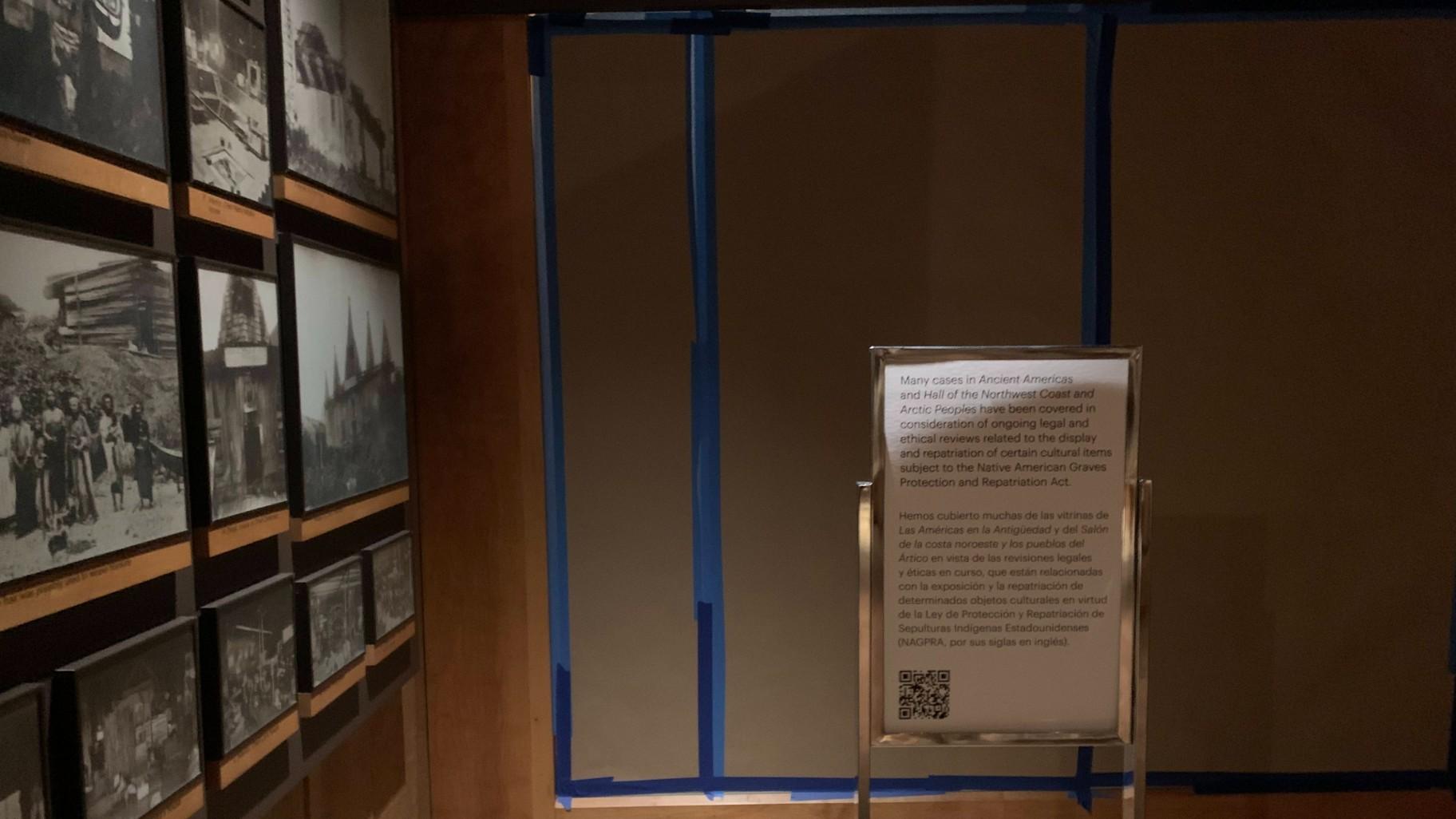

Covered display at the Field Museum on Jan. 31, 2024. (WTTW News / Eunice Alpasan)

Covered display at the Field Museum on Jan. 31, 2024. (WTTW News / Eunice Alpasan)

Recent visitors to the Field Museum’s Ancient Americas and the Northwest Coast and Arctic Peoples exhibits might have noticed covered-up display cases and portions of exhibits hidden behind curtains.

The museum is one of several across the country impacted by new federal rules that require museums and federal agencies to obtain “free, prior and informed consent” from affiliated tribes before displaying or doing research on Native human remains and cultural items.

In a statement to WTTW News, the Field Museum said it estimates hundreds of items that were on display are now under further evaluation following the new guidelines, adding the total number of items in its collections impacted by the new rules could be in the thousands.

But for some Native scholars and tribal historic preservation officers, the attempt at changes underway at several major institutions has been long overdue.

“What’s disappointing is that it takes a federal law to push institutions and agencies to comply and to even just create consultation with tribes,” said Eli Suzukovich, director of cultural preservation and compliance for the Office for Research at Northwestern University.

The federal guidelines are an update to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA) in an effort to speed up the process for museums to identify Indigenous remains and cultural items in their collections and return them to tribes.

An investigative report by ProPublica and NBC News published last year found some of the country’s top universities and museums exploited loopholes in NAGPRA to delay or resist turning over Native remains, funerary objects and cultural items.

While the Field Museum said it has no Native American human remains on display, it holds one of the largest collections of Indigenous remains in the country.

“Repatriation can be a lengthy process that requires consultation and collaboration,” a Field Museum spokesperson said in a statement. “Respectful consultation can take a long time, and the process can also be further complicated by multiple affiliated groups and/or when there isn’t robust documentation due to early collecting practices and avocational collectors.”

Covered displays at the Field Museum on Jan. 31, 2024. (WTTW News / Eunice Alpasan)

Covered displays at the Field Museum on Jan. 31, 2024. (WTTW News / Eunice Alpasan)

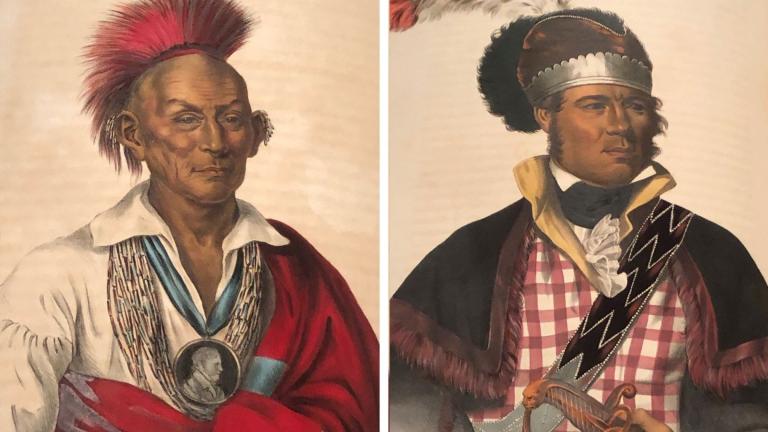

Raphael Wahwassuck, tribal council member for the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation in Kansas and member of the Field Museum’s repatriation task force, said outdated practices throughout history set the tone for how Native people and their land were viewed.

Many museums have operated for hundreds of years under that kind of mindset, he continued.

“I’m glad we’re at a point in history now where we can revisit some of the old notions, address those and make sure that we’re moving things forward in a better manner than what was done in the past,” Wahwassuck said. “Organizations profited quite a bit off of the bones and blood of our ancestors.”

In light of the updated federal regulations that went into effect Jan. 12, Wahwassuck said his tribal nation has been inundated with an increased volume of calls and emails from organizations inquiring about consultations.

He said keeping up with these requests might be an obstacle for a lot of tribes and tribal nations, who might only have a few members dedicated to working on NAGPRA-related issues.

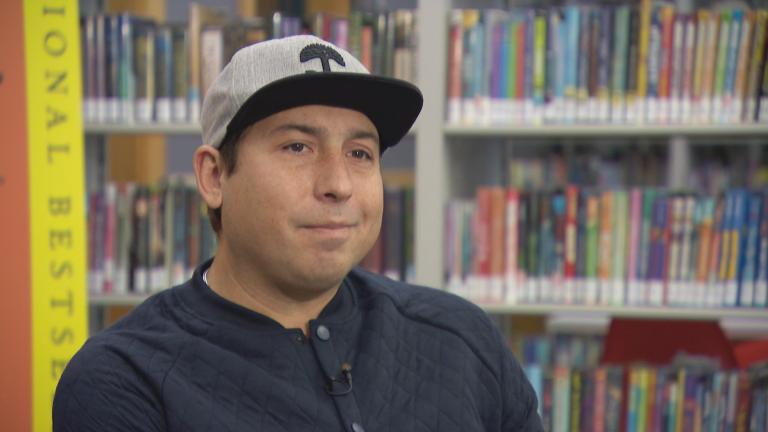

Matthew Bussler, tribal historic preservation officer of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians in Michigan, said that while he hasn’t seen major changes in his role since the new federal regulations went into effect, he expects an influx of museums and institutions to reach out either to engage in the NAGPRA process or to inquire about cultural items.

“Tribes need to be in control of what is being displayed and the narrative behind those exhibits, and tribal voices must inform their own story,” Bussler said in an interview on “Chicago Tonight.” “Museums should no longer be telling the story for us.”

Bussler said that in the past, he’s had to be proactive in his role by reaching out to institutions to determine the location of ancestral remains and their belongings. Since the new federal regulations took effect, he said he’s noticed more institutions reaching out first.

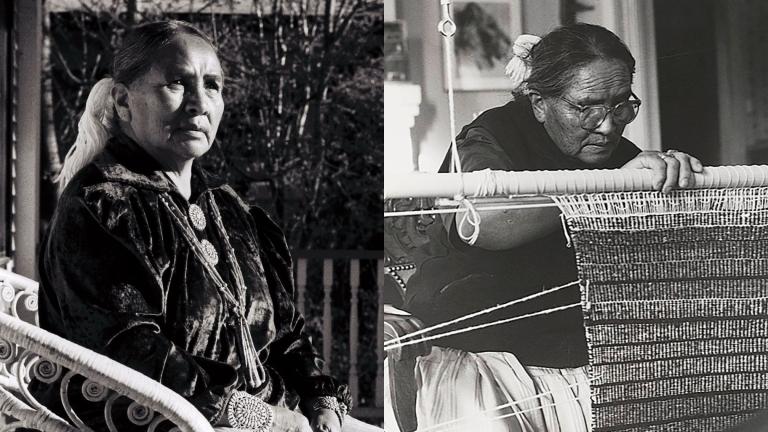

Gov. J.B. Pritzker signs bills establishing expanded protections for Native Americans in Illinois, including the Human Remains Protection Act (HB3413), on Aug. 4, 2023. (Governor JB Pritzker / Facebook)

Gov. J.B. Pritzker signs bills establishing expanded protections for Native Americans in Illinois, including the Human Remains Protection Act (HB3413), on Aug. 4, 2023. (Governor JB Pritzker / Facebook)

The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians were some of the tribes who were consulted and involved in Illinois passing a bill last summer that aims to streamline efforts to return Native American remains and cultural items uncovered in the state.

The Human Remains Protection Act, or House Bill 3413, also authorizes the creation of a cemetery in the state for the reburial of repatriated Native American remains and materials.

Wahwassuck said there are still ways for museums and historical societies to recognize and promote Native contributions, but that it needs to be done in collaboration with tribal nations and members of Native communities.

The Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston focuses on Indigenous histories, cultures and art. The museum has a majority Native leadership staff and board of directors.

The museum’s executive director, Kim Vigue, said that the museum listens carefully to Native communities and tribes in the area regarding any potential concerns over items in its collections and exhibits, even going beyond federal regulations and rules.

Over the past year, for instance, the museum has taken down eagle feathers and other items following requests and feedback from Native groups and tribal members. The museum also undergoes repatriation processes to get items back to their communities, Vigue said.

“For centuries, tribes have not been listened to at all,” Vigue said. “Native people and tribal nations need to be the storytellers of their own stories.”

Contact Eunice Alpasan: @eunicealpasan | 773-509-5362 | [email protected]