For some Black women, today is a day of dubious distinction.

Aug. 13, 2020 marks the number of days into this year that the average Black woman had to work to equal what the average white man earned last year, according to U.S. Census data. And despite studies showing that Black women as a group are just as educated and qualified as their white male counterparts, that gap has not narrowed for 25 years.

Cherita Ellens, president and CEO of nonprofit advocacy group Women Employed, says that one driver of the persistent gap is simply bias. She points to a Time’s Up Foundation study that found one of three men in hiring roles said that in times of job scarcity, they believed men are more entitled to jobs than women.

“Think about how you have all these people in decision-making roles that carry these biases of who belongs in the workforce and who should be getting paid top salaries and in leadership roles. This is further demonstrated by the fact that in Fortune 500 companies there are only 37 women leading, and none are Black or Latina,” said Ellens. “So this is not just about mentoring, coaching, and allyship, the issue is that biases, implicit or explicit, still exist. Until we put in systems that counteract these biases, we’re going to continue to have these issues of women being segregated into low-paying jobs and not advancing into the managerial and leadership roles.”

When asked if the gap is due to Black women disproportionately working in low-wage jobs, Ellens questions why those jobs are low-wage in the first place.

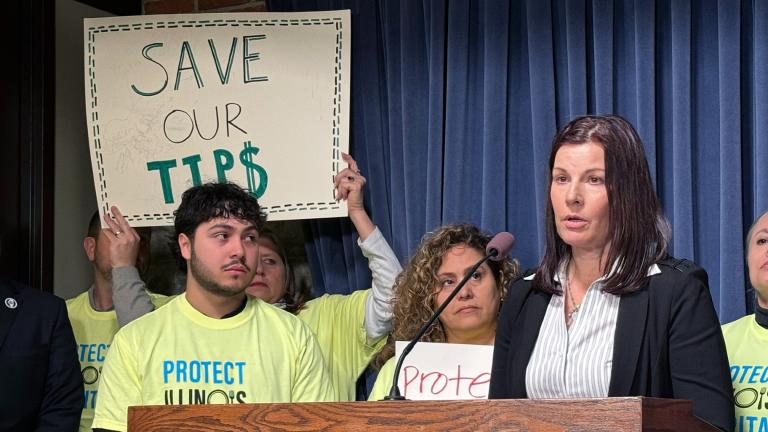

“Society has traditionally placed low value on the roles that are dominated by women…these are the roles of health care providers, home health aides, nursing assistants, teachers, retail and restaurant workers,” she said. “We have to begin to talk as a society about where we place our value. We have to shift to a mindset that these people that we depend on for everyday services, taking care of our kids, educating our kids, taking care of our elderly, deserve wages where they can live in dignity.”

In the current climate, Ellens says that Black women are also feeling sharper effects from the COVID-19 pandemic. “They’re affected in two ways. They’re on the front line, they have more risk to be impacted by COVID, but they’re also the ones that are losing their jobs at a higher rate,” she said.

And, she fears, the pandemic’s total effects have yet to be fully realized.

“There are a lot of women who carry the burden of caretaking that are still trying to do that and work a full-time job. The gains we’ve seen will begin to shrink because there will be women who need to leave the workforce, even if it’s just temporarily, to handle all these life responsibilities,” she said. “We have to begin talking about how the working world has to change to accommodate this. Less than half of these women have less than $200 in savings.”

Ellens says that more Black women are the primary breadwinners in their families than other demographic groups, so the downline effects of the wage gap can ripple through generations. “In Illinois, 67% of Black mothers are sole breadwinners…35% of Black female-led households…are at or below the poverty line.”

Overall, Ellens believes that society needs to shift the way it thinks about what work is worth. She points to her own experience growing up on Chicago’s Southwest Side as an example of how some types of labor have been devalued in recent decades.

“My father…worked at Cook County Hospital for 30-something years, but he was able to provide his family a good working-class life, live in a good neighborhood, send his kids to good schools, and still be home when we were home from school,” she said. “He was able to do that on his hourly wage. He didn’t have to work five jobs to do that. So we have to look at how we are valuing the American family and the dignity of work.”