For weeks, walkers, joggers and cyclists have been stopped in their tracks by an unexpected sight at Montrose Beach Dunes.

It’s Monty and Rose.

Chicago’s dearly departed piping plover lovebirds are back — sort of. The beloved duo live on in limestone, their instantly recognizable images carved into a block of the rock wall that separates the dunes from an adjacent paved path.

The memorial is the work of artist Don Di Sante. He’s the guy passersby may have seen hunched over the rock on and off since late August, bandana tied around his neck, arms covered in a pale denim shirt as protection against the sun.

“Those first few days, I was here for four hours and the sun was beating down on me,” Di Sante said. “It was too much.”

By mid-September, Di Sante, primarily a portrait painter who’d never carved rock before, had traded in the hammer and chisel he’d used to roughly sculpt Monty and Rose’s shapes for a file to add detail. For reference, he consulted a sketch he’d drawn — Rose positioned in nesting mode and Monty flapping his wings in the fierce protective stance plover monitors came to know and love. But the limestone wouldn’t always cooperate.

“Sometimes it flakes off, sometimes there’s little knots — you have to work with it or work around it,” Di Sante said. “I’ve actually broken off a few little things that should not have been broken off.”

The tip of Rose’s beak was one such casualty, a nick Di Sante wasn’t quite able to repair. Wary of making another mistake, Di Sante opted to leave Monty's legs thicker than the stick-like appendages he’d envisioned. Better for the bird to have cankles than accidentally dismembered limbs.

Artist Don Di Sante, finessing his carving of Monty and Rose. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Artist Don Di Sante, finessing his carving of Monty and Rose. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

With a painting, Di Sante said he knows he’s finished when he’s happy with the piece. The carving feels different to him. “I think I’ll visit every once in a while and bring tools with me,” he said.

If Di Sante seems reluctant to declare the carving a completed work, that’s partly because the experience has been such a joy.

“I love being here, just being able to work in this environment,” he said. “To look up and look at the lake, the sand, the (Montrose Point) bird sanctuary behind me.”

And, uncommon for a typically cloistered artist, there have been the interactions with people who stopped by for a closer look at the work in progress and to have a chat.

“If people recognize them as the plovers and know about the plovers, they absolutely love it and they thank me for doing it,” Di Sante said. “Other people think it’s pretty neat, even if they don't know what a plover is.”

On a recent afternoon, Di Sante was fiddling with minute adjustments to the plovers when a gentleman riding by on his bicycle hit the brakes to admire Monty and Rose. He gave the carving his stamp of approval and said the lakefront could use more like it. As the fellow pedaled off, Di Sante realized he missed a PR opportunity.

What he could have said: There already are carvings up and down the lakefront, hiding in plain sight. Thousands of them, like modern-day petroglyphs or cave drawings, dating back to at least the 1930s.

That tradition is what brought Di Sante to the rock, where he now joins a long history of Chicagoans leaving their mark on the city’s shoreline.

Video: Artist Don Di Sante talks about his tribute to Chicago’s beloved piping plovers, Monty and Rose, the latest addition to the collection of lakefront carvings. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

In the mid- to late 1980s, Aron Packer was living in Rogers Park and taking a photography class at the Evanston Art Center.

“I was trying to be an artist,” said Packer, who would go on to build a career as an art dealer and gallery owner.

Intrigued by the work of Aaron Siskind, famed for photographing objects and surfaces like peeling paint and cracks in asphalt, Packer was casting about for subject matter that might be termed “street poetry.”

“At some point or other, I saw these carvings out of the corner of my eye while I was riding on the lakefront,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘I bet these would photograph well.’”

In the right light, at the right time of day, they did, shadows playing up the incisions.

Starting at Foster and Bryn Mawr and then venturing further and further south to Montrose, Belmont, Fullerton, the Adler Planetarium, 33rd Street and Hyde Park, Packer found the carvings everywhere in the lakefront rock wall — the stair-stepped hunks of limestone piled up to keep Lake Michigan at bay.

He was struck by the sheer breadth of what he came to think of as a “folk sculpture,” all using the limestone rocks as canvas. There were horses, footprints and Old Style beer logos, some crudely done, some elegant and complex, like a moon landing scene carved with “adept capability,” Packer said. “That’s someone who knew their way around a chisel and hammer.”

In the early ‘90s, Packer’s photos of the carvings were exhibited at the Chicago Cultural Center, and he had an essay or two published in which he made the case for the significance of this miles-long open-air gallery.

“All this stuff was happening,” he said, but then interest kind of fizzled.

An Easter Island-style carving, salvaged at Fullerton, along the Chicago lakefront. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

An Easter Island-style carving, salvaged at Fullerton, along the Chicago lakefront. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

One person who remained gripped by the carvings was William Swislow, who’d learned about them through Packer.

Swislow, an editor with the Chicago Tribune at the time, was keenly interested in outsider art, or art by self-taught artists, and he considered the lakefront carvings excellent examples of such work.

But he became positively evangelical about the carvings during the course of an Army Corps of Engineers project to rebuild the lakefront revetments, a process that involved tearing out miles of the limestone blocks and replacing them with concrete.

“Up until the lakefront project, I took it for granted the carvings would be there. I had no idea until it was too late. I wasn’t really aware of the Army Corps project until they were already ripping up the rocks,” Swislow said.

And with the rocks, went the carvings.

“Thousands gone,” he said, many of them never photographed. “Most were just destroyed or dumped in the lake and crushed.” (Some at Belmont were salvaged thanks to the intervention of Ald. Tom Tunney and at Fullerton by the project’s landscape architect.)

Swislow took it upon himself to document what remained, from the most basic carvings of initials to museum-quality works. “I’ve walked almost all of the structures, starting at the Indiana state line up to Hollywood,” he said. “I have 2,400 unique photos.”

What he gradually became convinced of, having experienced the carvings in their totality, is that the individual pieces form an unconscious collective work. Everyday Chicagoans, whose lives will never rise to a level considered worthy of a public monument, chose to create one to themselves, by themselves.

“It’s this self-made monument to summers by the lake. It’s this legacy, these traces of people’s identity, back to the 1930s,” Swislow said. (The earliest date attached to a carving is 1931.) “It gives these six miles of limestone blocks a human texture. Almost all of Chicago’s lakefront is engineered — this looks real. It is delightful.”

Along with gathering photos, Swislow has collected stories of a handful of carvers, who, with rare exception, remain anonymous.

There’s the steelworker who just wanted to try his hand at self-portrait in the 1950s. The lifeguards at Rainbow Beach in the 1960s who etched their initials as a rite of passage. The bored University of Chicago freshman who chiseled the name of his girlfriend decades ago, never took her to see the tribute, but has been married to her all these years later.

The great mystery is the identity of the man both Swislow and Packer independently saw working on a series of 12 intricate carvings at Foster. Only recently has Swislow learned that the Mayan-esque scenes are indeed inspired by actual Mayan ruins.

The “why” is as intriguing to Swislow as the “who.” “It wasn’t casual,” he said.

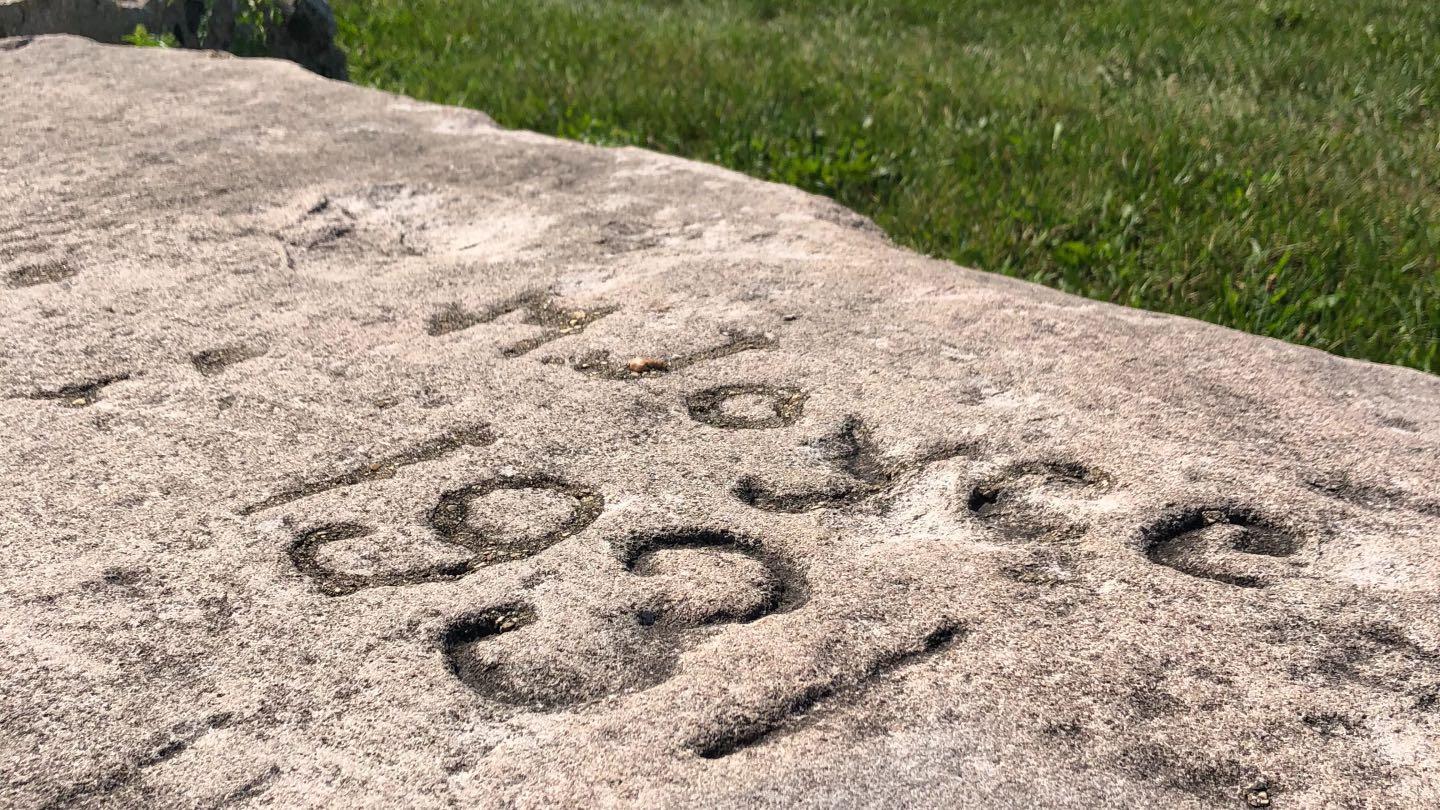

"M. Joyce 1931," the carving with the oldest date attached, salvaged at Belmont. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

"M. Joyce 1931," the carving with the oldest date attached, salvaged at Belmont. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Among the hordes of Chicagoans and tourists who flock to the city’s lakefront every summer, Swislow said there’s “zero awareness” of the carvings.

“I talk to people and most people say, ‘I’ve never noticed these.’ If no one’s aware of these carvings, they get destroyed,” he said.

With the Army Corps of Engineers having recently announced plans to begin a study of future lakefront protections, Swislow is deeply worried that the remaining miles of limestone — largely along the south lakefront — are in danger of going the way of rocks at Belmont, Fullerton and Montrose.

He fears for treasures at Promontory Point, Morgan Shoals and a section behind La Rabida Children’s Hospital, where one of his favorite rocks could be lost. “There’s this ‘peace rock’: It has a peace symbol, butterflies and flowers. It’s the hippy summer of love covered in one rock.”

And he fears for treasures yet to be discovered. Thanks to lower lake levels, Swislow found new carvings this summer, one at Rainbow Beach and a 12-panel collection, dated 1948-1952, south of La Rabida, 15 feet off shore.

To raise the alarm about the potential disappearance of a piece of cultural heritage most Chicagoans don’t even know exists, Swislow and Packer combined their photo archives and published, “Lakefront Anonymous,” an illustrated history of the lakefront carvings, in 2021.

The book’s designer? The plover carver Don Di Sante.

Video: A gallery of stone carvings along Chicago’s lakefront, from Foster Beach to Fullerton Beach. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Di Sante moved to Chicago in the late 1970s to attend college and never left. Even though he’s been riding his bike up and down the lakefront for as long as he can remember, working on “Lakefront Anonymous” was a revelation, he said, and it left him with the itch to try a carving of his own.

He practiced his technique first, pounding out a star at Wilson. For the main event, Monty and Rose were a natural choice of subject matter.

Though he doesn’t necessarily consider himself a birder, Di Sante frequently volunteers during stewardship days at the Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary.

He recalled hearing through the grapevine that piping plovers had been spotted at Montrose Beach back in 2019, and assumed, given the level of excitement, that meant an entire flock had descended.

“Then I find out it’s just two birds,” Di Sante said.

But those two birds brought a city together, even if for a short time, and that’s something worth commemorating. The carving might not say so in words, but its message is as clear as every other name and drawing etched into stone.

Monty and Rose were here.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]