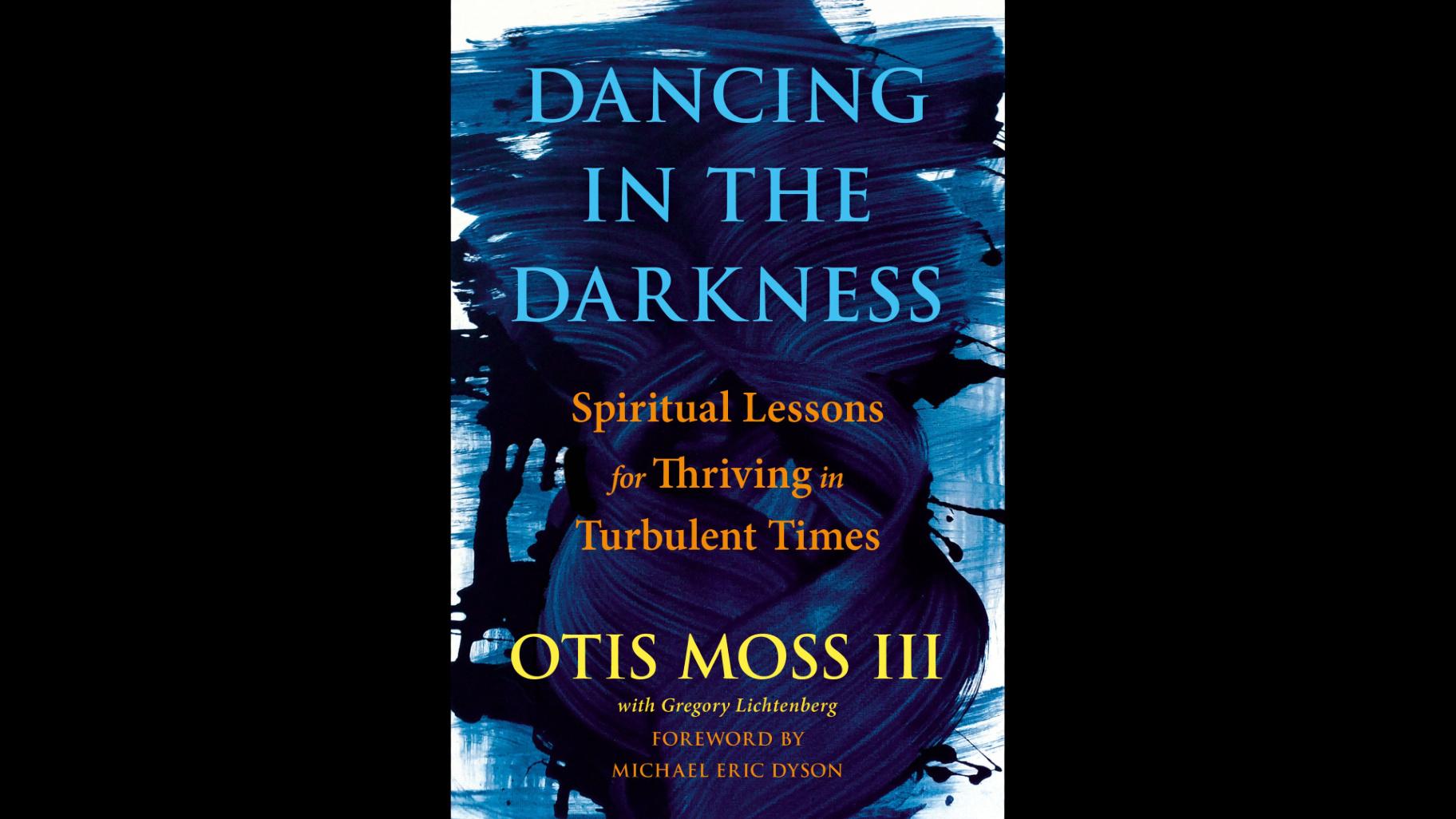

In days when the bonds holding the country together can feel fragile, it can be difficult to see past the worry and anger in order to work toward justice. In his new book, “Dancing in the Darkness: Spiritual Lessons for Thriving in Turbulent Times,” the Rev. Otis Moss III of Trinity United Church of Christ draws upon stories from his congregation, his forebearers and his own family and weaves them into a guide for practicing spiritual resistance in everyday lives.

Moss said the book’s title comes from an experience with his daughter in 2008, when then-Sen. Barack Obama, who was a Trinity congregant, was running for president and both the church and Moss’ predecessor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, were targets for threats and harassment. Moss said the church and its staff hired security, but the worry of an attack was ever-present.

“One evening we heard something in the house and my wife tapped me and said, ‘[You] need to check that out,’” Moss recalled. “So I grabbed my rod and my staff that comforts me — that being a Louisville slugger — and looked around the house and I heard the noise again coming from my daughter's bedroom, and I'm thinking that someone broke into our home. Was I going have to defend my children and my wife? I come into my daughter’s room and there she is in the middle of the room and she’s dancing. She’s saying, ‘Look, daddy, I'm dancing.’ It's 3 a.m. So I get that fatherly voice — ‘Baby, you need to go to bed.’ But then the spirit just rested on me and said, ‘Look at your daughter, she’s dancing in the darkness. The darkness is around her, but it’s not in her.’ And at that moment, I ran down to my study and I just started writing until the sun came up. And when I finished, I stepped into the pulpit and said, ‘We are called to dance in this darkness, dance with love, with joy, with justice, with compassion, with dignity.’”

The words and work of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who officiated the wedding of Moss’ parents, are woven throughout the book. Moss said he sees many parallels between the times in which King lived and the present day.

“Dr. King talks about: What does it mean to have a complete life? Personal, the commitment that you must have, and the spiritual, and that’s still true today, that if you want to have a complete life and create a new society, there has to be the personal dimension,” Moss said. “There has to be the commitment to community and then there has to be the spiritual dimension. And so Dr. King was dealing with a time period of chaos in American civil society and then made the choice to say that we can build a ship in the midst of this chaos to move toward a beloved community. … I believe that activists today are doing the same thing of building this ship, a ship that is rooted in this idea of justice, rooted in this idea of compassion and reciprocity and restoration versus retribution, which is very different.”

Moss said he finds inspiration for working toward justice in a variety of faiths and traditions.

“I use the example of the Babemba tribe in South Africa,” Moss said. “When a young person makes a transgression against the community, instead of casting them out, they create a circle of elders and of young people and instead of saying, ‘Look what you did wrong,’ they say, ‘Let me tell you how much potential you have, let me tell you how powerful you are, if you will live up to your potential.’ They do that for hours, sometimes days and even weeks until the young person breaks down and says, ‘I have to live out the calling of my tradition.’”

Though Moss is himself a Christian, he said the lessons he shares in his book are universal.

“If I’m agnostic or if I am non-religious, I can embrace the idea of what should our nation look like, what values that I must live out,” Moss said. “We must use the idea of love, of courage, of reciprocity, of compassion, of justice. No matter where you are from, those particular values are necessary for a human being to flourish.”

Read an excerpt from the book below.

"Dancing in the Darkness: Spiritual Lessons for Thriving in Turbulent Times" by Otis Moss III with Gregory Lichtenberg

"Dancing in the Darkness: Spiritual Lessons for Thriving in Turbulent Times" by Otis Moss III with Gregory Lichtenberg

Agape love is the love that seeks to care for what it loves, whether that is a child, a partner, the land we were given, the community in which we live, or the truths we hold to be self-evident. Agape love recognizes that we must become stewards, focused not only on the wrong of the moment but on building a better future.

When you start to look for it, you can see examples of love combined with justice where you might least expect it. In the rules of sports, which must serve the needs of all the players, harm to one player is remedied with a chance to address that harm in a way that restores the whole team. If an opposing player hits you during a basketball game, you have been wronged, and it is called a foul. You may want some justice. You could get your justice by hitting the other player in the face. The rules of basketball, though, say that you do not get to punch the other player. Instead, you get a free shot. You have a chance to do some harm to the other player’s team within the game, not outside of it. That keeps the game going, while a punch might have ended the game and started a brawl. The other team is motivated to teach their players to avoid reckless fouls in the future because those penalty shots hurt the entire team. In this way, the rules of basketball provide justice in the moment but also serve the future of the game by motivating all the players to play more responsibly.

If you are fouled in soccer, you are allowed a penalty kick. In hockey, if you foul another player, you are taken out of the game for a set period of time and put in the penalty box. The rest of the team has to struggle without you, so again, not only is justice done for the player who was wronged, but your entire team is motivated to teach a reckless player to repair their style of play.

We have the opportunity to link love and justice in any situation in which a wrong has been done. If a child has broken a rule or gone in a direction a parent does not desire, yelling and grounding will achieve a measure of justice. But if your goal as a family member or a teacher is more than simply measuring out the accepted dose of punishment—that is, if you care whether the child repairs what is broken and returns to a better path—then you need to plan and explain a lesson the child can use. Your justice needs to be linked with love.

You will find a version of agape love in all of the world’s great spiritual traditions. The Buddhist writer Thich Nhat Hanh explained that love seeks to alleviate suffering. If you love someone, he said, then you cannot want them to suffer. So love must work to understand suffering and then to address the causes of suffering. Buddhist love is love linked with justice.

In the Yoruba tradition, ethics are not rooted in the individual but in the flourishing of the community. True love, then, includes respect, diligence, accountability, truthfulness, devotion, and loyalty. Love cannot be love without justice.

The love ethic was central in the life of Jesus, defining what it means to be one of His followers. Jesus taught that you must preach love not by what you say in the pulpit but by what you do, the actions you take from the moment you get up to the time you rest your head on the pillow. In the Book of Matthew, he chides his followers for failing to understand the complexity and beauty of his mission with a story. He shares the imagery of when the son of mankind comes in glory as a king, and describes the king speaking to his followers, saying, “I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink. I was a stranger and you did not invite me in. I needed clothes and you did not clothe me. I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.”

His followers object, asking the king to tell them a specific occasion when they failed him in one of these ways.

And the king replies, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.” He is saying that the love ethic is measured by how we care for those least able to care for themselves, whether because they lack food, drink, clothes, a home, a community, medical care, or freedom. His true followers are those who work to drive out fear, address inequality, and confront the opposite of love, which is indifference and hate.

When Dr. King published a book of his most requested sermons in 1963, he had to choose one sermon to provide the title of the book and speak for all the rest. He chose “Strength to Love,” because he believed that love was the most difficult virtue to live. The question each of us must ask about love—deep, spiritual, agape love—is whether we have the strength of commitment that is required to link love to justice.

Excerpted from "Dancing in the Darkness: Spiritual Lessons for Thriving in Turbulent Times" by Otis Moss III with Gregory Lichtenberg. Copyright © 2023 by Reverend Otis Moss III. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.