Chicago spent just 29% of the federal relief funds officials promised to use to strengthen the city’s tattered social safety net and provide direct aid to Chicagoans struggling to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic by the end of 2023, according to a WTTW News analysis.

In all, Chicago spent less than $160 million on a host of programs including affordable housing, mental health, violence prevention, youth job programs and help for unhoused Chicagoans through Dec. 31, according to the most recent reports filed with the U.S. Department of the Treasury as required by federal law.

Chicago’s entire budget for the federally funded programs is approximately $550 million, records show.

The city spent an additional $1.2 billion in federal COVID-19 relief funds to shore up Chicago’s pandemic-devastated budgets from 2021 through 2023, with approximately $250 million left unspent as of the end of 2023, according to the Treasury Department reports.

WTTW News’ analysis is the first to examine two years’ worth of reports from city leaders to federal officials documenting how Chicago has spent the city’s $1.9 billion share of the federal relief package known as the American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA.

Those records, published online by the city’s Budget Office without any notice to the public or the City Council, show city officials have struggled to make good on promises to use the influx of cash from the federal government to repair the damage caused by the pandemic, which has killed nearly 8,300 Chicagoans, hospitalized another 57,000 and upended the lives of millions across the U.S.

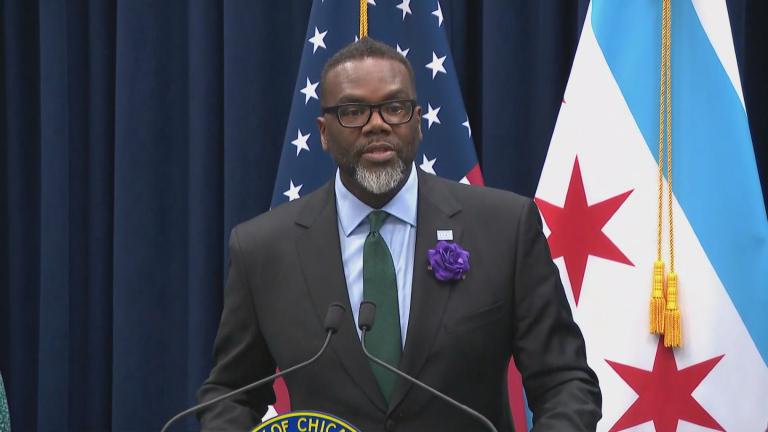

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s decision in late December to dip into that bucket of unspent federal cash and earmark $95 million to care for some of the nearly 35,400 migrants sent to Chicago from the southern border has renewed questions about whether the windfall of federal funds is being spent appropriately under adequate oversight by the Chicago City Council.

Under rules established by the federal government, Chicago officials have until 2026 to spend all of the federal funds the city got to repair the damage caused by the pandemic, which unleashed an economic catastrophe that helped fuel a surge in crime that has yet to fully recede.

However, the money must be budgeted by the end of year, which means Johnson is facing a rapidly ticking clock as he weighs whether to revamp the Chicago Recovery Plan crafted by his predecessor, former Mayor Lori Lightfoot.

Ald. Matt Martin (47th Ward), who was the vice chair of a City Council subcommittee created in 2021 to keep tabs on the plan’s progress and speed the flow of cash, said it was “very disappointing” that the city was not able to spend the federal relief funds more quickly.

“We certainly should have spent the bulk of this money by now, when the pandemic was raging,” Martin said. “We have to take a hard look at why we let millions of dollars sit on the shelf while people were suffering.”

Budget Director Annette Guzman told WTTW News she was determined to spend every penny of the city’s share of federal COVID-19 relief funds before the deadlines set by the federal government in the most effective way possible.

Guzman acknowledged she is frustrated that the city had not moved faster to spend the funds that promised to fuel proposals that had languished for years because of a lack of cash.

“One of my mandates when I came in from the mayor was to fix ARPA,” Guzman said. “And to make sure we are getting this money out to people who need it the most, we’re finding ways to break down any bureaucratic obstacles or structures that frustrate that effort.”

The city ramped up ARPA spending significantly during 2023, as compared with 2022, when Chicago spent less than $30 million by the end of the year on recovery projects, according to its reports to the Treasury Department.

That is significantly less than the $130 million the Lightfoot administration told the City Council it had spent by September 2022, according to a report provided to City Council members that was later removed from the web after it was detailed by WTTW News.

During hearings before the approval of the city’s 2023 budget, department leader after department leader detailed struggles around completing requests for proposals, selecting organizations to complete the work and cutting the checks because of the crush of other work and the high number of vacancies in the city.

In retrospect, the city never overcame those obstacles, Martin said.

City officials struggled to meet the guidance issued by federal officials to ensure appropriate programs and projects were funded, Guzman said. Chicago officials have done an immense amount of work to spend as much money as quickly as possible, without wasting a single cent, she added.

“No one wants to keep this money,” Guzman said. “No one is hoarding money.”

Chicago is not alone in struggling to spend all of the federal COVID-19 relief funds it got in 2021 by 2026, said Amanda Kass, an assistant professor in DePaul University’s School of Public Service who is studying how cities are spending ARPA dollars.

The process of how these funds are being spent is “opaque” with very little sense of whether they are actually making a difference in people’s lives, Kass said.

“We don’t have a lot of clarity about what’s behind those numbers,” Kass said.

Guzman declined to directly criticize the way the Lightfoot administration spent federal COVID-19 relief funds, but said she took a different approach when she led Cook County’s budget office in 2021 and 2022 that prioritized speed. That approach will serve Chicago better in the long run, she said.

“This is an opportunity for our city to tell the federal government, ‘Look, this is what is needed in our jurisdictions, and this is what we know works, and here’s the impact that these dollars were able to bring into our communities,’” Guzman said. “We’re close to figuring out how we are going to make our mark on it.”

Not only has the city been slow to ink contracts with nonprofits to do the work called for by the Chicago Recovery Plan, but the flow of funds meant to expand direct city services has been sluggish at best, according to the data.

For example, the plan earmarked $19 million for the Community Safety Coordination Center, which is designed to respond to emerging crime trends by addressing the root causes of crime by providing jobs, counseling and educational services. That approach is at the heart of the promises Johnson made during his campaign to tackle public safety holistically — not just with arrests and law enforcement.

But just $7 million had been spent on the center by Dec. 31, despite a clear consensus across the political divide that the city must step up efforts to reduce violence to truly recover from the pandemic.

Guzman said issues like that are part of the ongoing efforts to fix what’s wrong with ARPA, but acknowledged that a complete overhaul of the Chicago Recovery Plan is “improbable” because of the looming deadlines, even as she conducts an analysis of the program.

“There is some work we can do to align with the mayor’s goals,” Guzman said, adding that she was also committed to doing a better job showing Chicagoans what the city got in return for its investment of nearly $2 billion.

That analysis is likely to be complete by early spring, and will include a renewed commitment to transparency, Guzman said, adding that the Johnson administration removed a dashboard designed by the Lightfoot administration that tracked ARPA spending because it lacked the proper context.

Martin said he and other members of the City Council would welcome that transparency, which he said was crucial if city officials are to fulfill their promises to use these federal grants to help Chicagoans recover from a once-in-a-century pandemic.

“We need to be honest about what’s working and what’s not working, and course-correct,” Martin said, adding that he was particularly angry that the city spent only $462,000 to expand broadband internet connections across Chicago even though the city had budgeted $10 million for the program.

Johnson should double down on the programs that have already worked, including the $31.5 million effort that sent $500 per month for a year to 5,000 Chicagoans living below the federal poverty line as part of an effort to test a guaranteed basic income program, Martin said.

“That was a clear success,” Martin said, noting that an analysis showed those who participated in the program paid down debt, spent more time with their families and got better jobs.

A similarly successful program used $5 million for one-time payments of $1,000 to people who were victims of intimate partner violence or other kinds of violence because of their gender, Martin said.

That program should be expanded not only because it has been proven to work but because the number of homicides connected to incidents of domestic violence is increasing, even as the overall number of murders drops, Martin said.

Another program that should be expanded is the city’s rapid rehousing program, which is designed to help residents of encampments secure housing and services in one day, Martin said. The city’s watchdog found 94% of participants found an apartment, with nearly 79% of participants still housed five months later.

The city set aside $27.3 million for that program, but has spent less than $12.9 million, records show.

With homelessness surging in Chicago, expanding that program is essential, Martin said.

Ald. Daniel La Spata (1st Ward), who has long been critical of the glacial pace of spending to combat gender-based violence, said he was furious the city had not done a better job of addressing such a clear and present need.

Chicago spent $7.8 million of the $20 million officials earmarked for five programs designed to reduce gender-based violence, according to the reports to the treasury departments.

“It is taking much longer than it should,” La Spata said.

Part of that course correction should be increased oversight by the City Council, said Ald. Bill Conway (34th Ward), who crafted a measure that would have required the Johnson administration to get explicit approval from the City Council before spending more than $1 million in ARPA funds.

City officials told the Treasury Department it was necessary and appropriate to use unspent ARPA funds to house, feed and provide medical care for the migrants because “the COVID-19 pandemic has led to greater instability of housing, public health concerns, and economic hardship for asylum-seeking residents within the city’s jurisdiction.”

Allies of the mayor blocked Conway’s ordinance from advancing last month, and it is unclear whether it will get a hearing or a vote.

Johnson should consult more frequently with alderpeople about how ARPA funds are being spent, Conway said.

“We want to make sure this money is being used for the long-term benefit for all of Chicago,” Conway said.

Third Stream of Money Starts to Flow

On top of the federal COVID-19 relief funds, the plan crafted by Lightfoot called for the city to borrow an additional $660 million to help mend the city’s social safety net and address long-standing needs, like the expansion of affordable housing and efforts to combat climate change.

In 2023, city officials borrowed $170 million to fund those projects, officials said.

Officials have spent approximately $94 million in bond funds on four dozen projects ranging from electric car charging stations to food composting programs and affordable housing projects, according to a list provided to WTTW News by city officials.

That amounts to just 14% of the overall bond-funded program unveiled with much fanfare nearly two and a half years ago.