Matt Taibbi is arguably one of the most influential journalists of his age. He's perhaps best known for his work covering the financial crisis as a contributing editor for Rolling Stone magazine. He famously described Goldman Sachs as "a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money." Clearly not shy about expressing his opinions, Taibbi has a new book out called The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap. He joins us.

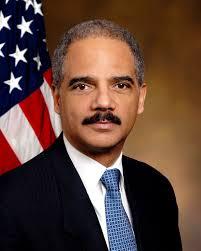

In his book, The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, Matt Taibbi refers to then Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder’s collateral consequences, which are part of the Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations.

In his book, The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, Matt Taibbi refers to then Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder’s collateral consequences, which are part of the Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations.

The Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations is a set of guidelines for prosecuting corporations and business organizations. These guidelines were issued by the Department of Justice in 1999.

The guidelines list nine factors that should be considered when deciding whether to charge a corporation or business. The guidelines are as follows:

- the nature and seriousness of the offense, including the risk of harm to the public, and applicable policies and priorities, if any, governing the prosecution of corporations for particular categories of crime;

- the pervasiveness of wrongdoing within the corporation, including complicity in, or the condoning of, the wrongdoing by corporate management;

- the corporation’s history of similar misconduct, including prior criminal, civil, and regulatory enforcement actions against it;

- the corporation’s timely and voluntary disclosure of wrongdoing and its willingness to cooperate in the investigation of its agents;

- the existence and effectiveness of the corporation’s pre-existing compliance program;

- the corporation’s remedial actions, including any efforts to implement an effective corporate compliance program or to improve an existing one, to replace responsible management, to discipline or terminate wrongdoers, to pay restitution, and to cooperate with the relevant government agencies;

- collateral consequences, including whether there is disproportionate harm to shareholders, pension holders, employees, and others not proven personally culpable, as well as impact on the public arising from the prosecution;

- the adequacy of the prosecution of individuals responsible for the corporation’s malfeasance; and

- the adequacy of remedies such as civil or regulatory enforcement actions

The collateral consequences condition allows prosecutors to consider the potential impact a criminal conviction of a corporation would have when determining whether to charge a corporation with a criminal offense.

The collateral consequences condition allows prosecutors to consider the potential impact a criminal conviction of a corporation would have when determining whether to charge a corporation with a criminal offense.

“In the corporate context, prosecutors may take into account the possibly substantial consequences to a corporation's officers, directors, employees, and shareholders, many of whom may, depending on the size and nature (e.g., publicly vs. closely held) of the corporation and their role in its operations, have played no role in the criminal conduct, have been completely unaware of it, or have been wholly unable to prevent it,” as stated in the Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations.

While the memo states that the potential impact on “innocent third parties” should not prevent prosecution of a corporation, the weight given to collateral consequences may depend on special policy concerns, which include the nature and seriousness of the crime and risk of harm to the public.

“For instance, the balance may tip in favor of prosecuting corporations in situations where the scope of the misconduct in a case is widespread and sustained within a corporate division (or spread throughout pockets of the corporate organization). In such cases, the possible unfairness of visiting punishment for the corporation's crimes upon shareholders may be of much less concern where those shareholders have substantially profited, even unknowingly, from widespread or pervasive criminal activity. Similarly, where the top layers of the corporation's management or the shareholders of a closely-held corporation were engaged in or aware of the wrongdoing and the conduct at issue was accepted as a way of doing business for an extended period, debarment may be deemed not collateral, but a direct and entirely appropriate consequence of the corporation's wrongdoing,” as stated in the Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations.

Read an excerpt from The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap below.

Over the course of the last twenty years or so, America has been falling deeper and deeper into a bizarre statistical mystery.

Take in the following three pieces of information, and see if you can make them fit together.

First, violent crime has been dropping precipitously for nearly two decades. At its peak in 1991, according to FBI data, there were 758 violent crimes per 100,000 people. By 2010 that number had plunged to 425 crimes per 100,000, a drop of more than 44 percent.

The decrease covered all varieties of serious crime, from murder to assault to rape to armed robbery. The graphs depicting the decline show a long, steady downswing, one that doesn’t jump from year to year but consistently slumps from year to year.

Second: although poverty rates largely declined during the 1990s, offering at least one possible explanation for the drop in violent crime, poverty rates rose sharply during the 2000s. At the start of that decade, poverty levels hovered just above 10 percent. By 2008 they were up to 13.2 percent. By 2009 the number was 14.3 percent. By 2010, 15.3 percent.

All this squares with what most people who lived in Middle America knew, and know, instinctively. Despite what we’re being told about a post-2008 recovery, despite what the rising stock market seems to indicate, the economy is mostly worse, real incomes are mostly declining, and money is mostly scarcer.

But throughout all this time, violent crime has gone down. It continues to decline today. Counterintuitively, more poverty has not created more crime.

The third piece of information that makes no sense is that during this same period of time, the prison population in America has exploded. In 1991 there were about one million Americans behind bars. By 2012 the number was over 2.2 million, a more than 100 percent increase.

Our prison population, in fact, is now the biggest in the history of human civilization. There are more people in the United States either on parole or in jail today (around 6 million total) than there ever were at any time in Stalin’s gulags. For what it’s worth, there are also more black men in jail right now than there were in slavery at its peak.

See if this syllogism works, then.

Poverty goes up;

Crime goes down;

Prison population doubles.It doesn’t fit, unless some sort of alternative explanation comes into play. Maybe all those new nonviolent prisoners fit into some new national policy imperative. Maybe they all broke some new set of unwritten societal rules. But what?

While on a visit to San Diego to do research for this book, I heard a crazy story.

The subject was the city’s P100 program, under which anyone who applied for welfare could have his or her home searched preemptively by the state. Ostensibly, authorities were looking for evidence that the applicant had a secret job or a boyfriend who could pay bills, or was just generally lying about something in order to cheat the taxpayer out of that miserable few hundred bucks a month.

One Vietnamese woman, a refugee and a rape victim who had only recently come to America, applied for welfare in San Diego. An inspector came to her door, barged in, and began rifling through her belongings. At one point, he reached into her underwear drawer and began sifting around. Sneering, he used the tip of the pencil eraser to pull out a pair of sexy panties and looked at her accusingly. If she didn’t have a boyfriend, what did she need these for?

That image, of a welfare inspector sneeringly holding up panties with a pencil end, expresses all sorts of things at once. The main thing is contempt. The implication is that someone broke enough to ask the taxpayer for a handout shouldn’t have sex, much less sexy panties.

The other thing here is an idea that being that poor means you should naturally give up any ideas you might have about privacy or dignity. The welfare applicant is less of a person for being financially dependent (and a generally unwelcome immigrant from a poor country to boot), so she naturally has fewer rights.

No matter how offensive the image is, it has a weird logic that’s irresistible to many if not most Americans. Even if we don’t agree with it, we all get it.

And that’s the interesting part, the part where we all get it. More and more often, we all make silent calculations about who is entitled to what rights, and who is not. It’s not as simple as saying everyone is the same under the law anymore. We all know there’s another layer to it now.

As a very young man, I studied the Russian language in Leningrad, in the waning days of the Soviet empire. One of the first things I noticed about that dysfunctional wreck of a lunatic country was that it had two sets of laws, one written and one unwritten. The written laws were meaningless, unless you violated one of the unwritten laws, at which point they became all-important.

So, for instance, possessing dollars or any kind of hard currency was technically forbidden, yet I never met a Soviet citizen who didn’t have them. The state just happened to be very selective about enforcing its anticommerce laws. So the teenage farsovshik (black market trader) who sold rabbit hats in exchange for blue jeans outside my dorm could be arrested for having three dollars in his pocket, but a city official could openly walk down Nevsky Avenue with a brand-new Savile Row suit on his back, and nothing would happen.

Everyone understood this hypocrisy implicitly, almost at a cellular level, far beneath thought. For a Russian in Soviet times, navigating every moment of citizenship involved countless silent calculations of this type. But the instant people were permitted to think about all this and question the unwritten rules out loud, it was like the whole country woke up from a dream, and the system fell apart in a matter of months. That happened before my eyes in 1990 and 1991, and I never forgot it.

Now I feel like I’m living that process in reverse, watching my own country fall into a delusion in the same way the Soviets once woke up from one. People are beginning to become disturbingly comfortable with a kind of official hypocrisy. Bizarrely, for instance, we’ve become numb to the idea that rights aren’t absolute but are enjoyed on a kind of sliding scale.

Excerpted from THE DIVIDE: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap. Copyright © 2014 by Matt Taibbi. Excerpted with permission of Spiegel & Grau, a division of Random House, Inc.

~ Paul Caine contributed to this report.