Chicago is not defined solely by its human residents. It’s a city with a living, evolving "ecological web of interactions" between man and animal, according to Gavin Van Horn, the director for the Center for Humans and Nature, a Chicago nonprofit that promotes conservation ethics.

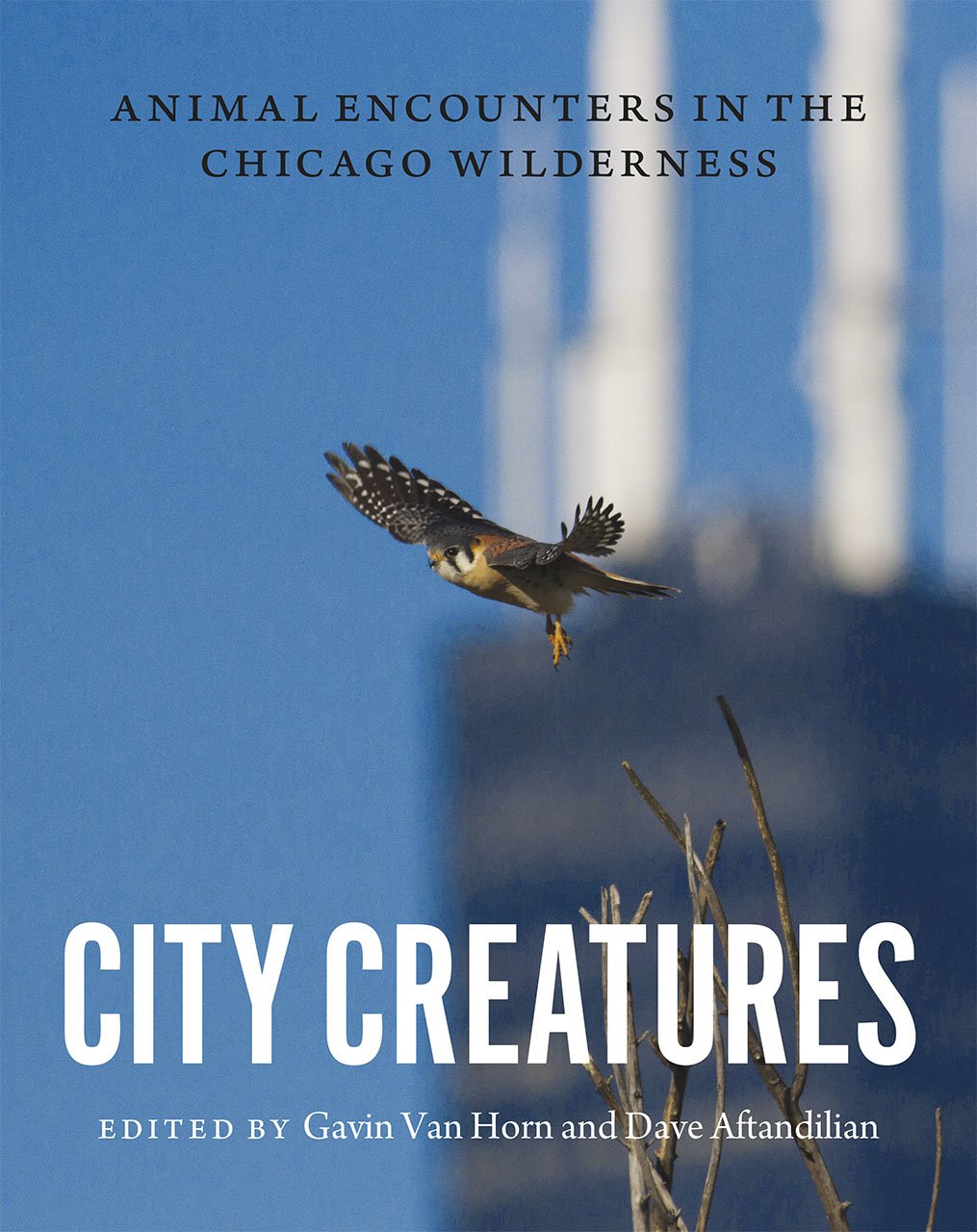

He curated and edited the book “City Creatures,” which details urban wildlife history through essays, poetry, photography and paintings.

An exhibition at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum is based on the book and continues through Jan. 3. Van Horn joins "Chicago Tonight" to discuss the book and exhibit.

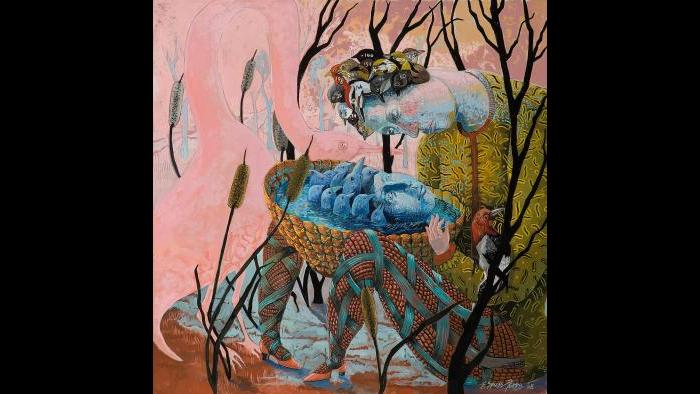

Below, some of the featured artwork from "City Creatures."

Book review: 'City Creatures'

The book “City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness” features natural histories and intimate reflections on the area’s wildlife from a variety of contributors. The stories are told through personal narrative essays, thoroughly researched articles, poetry and visual art such as murals and photographs. The result is a vivid and detailed depiction of Chicago’s natural world, pieced together by several perspectives spanning the city and suburbs.

The book’s strength is that it lacks the arcane scientific terminology or tiresome data that one might expect from a work of this sort. The historical findings included in the essays are typically paired with an author’s personal experiences, effectively linking fact with feeling. Editors Gavin Van Horn and Dave Aftandilian divided their book into six sections, each representing a different niche within Chicago’s natural world.

The first section is called “Backyard Diversity.” The featured works are influenced by the close encounters Chicagoans have with animals in and around their homes. Amy Newman’s poems “Raccoon” and “The Fox” are included here. Newman personifies these critters that roam our neighborhoods, assigning intentions and emotions to their furtive movements.

The second chapter, “Neighborhood Associations,” touches on the interactions between humans and animals throughout Chicagoland – in what’s described as the “liminal spaces neither fully wild nor fully domestic.” Our connection with the natural world, whether physical or imagined, is explored in this segment of the book. The poem “Pigeons” by David Hernandez uses these birds, sometimes pejoratively referred to as “winged rodents,” as a metaphor for the Hispanic community. With raw, unfiltered language, the poet draws parallels between the squalid surroundings and reviled reputation of pigeons with the ongoing struggle of Chicago’s Latin American population. Naturalist Joel S. Brown’s essay on squirrels, “A Tale of Two Squirrels and One City,” distinguishes between two types of squirrels found in Chicago: the fox squirrel and the grey squirrel. Brown writes about the behavioral differences between these two species as well as how increasingly engaged his students at University of Illinois at Chicago become while learning about them.

Many visitors to Chicago interact with animals behind glass or metal enclosures. These scenarios are explored in the third section, “Animals on Display.” The traditional environments in which urbanites observe animals – zoos, museums and aquaria – form the basis here. Naturally, this is a complicated portion of the book as writers wrestle with the morality of confining animals for human observation. Beautiful yet heartrending photographs of colorful bluebirds and cardinals stuffed and encased at the Field Museum are displayed in this chapter.

The fourth section, “Connecting Threads,” is dedicated to the areas reserved for the safeguard and enjoyment of wildlife: parks, forest preserves and other protected lands. The book’s conservation message rings loud and clear in this chapter. Stephan Swanson writes both personally and historically of the rise and fall of the eastern massasauga rattlesnake, a snake species that once flourished in Chicagoland before it was hunted to near-extinction in the latter half of the 20th Century.

The section “Water Worlds” is plainly and deliberately named – it focuses on the area’s waterways and bodies of water along with the wildlife that inhabit them. Rounding out the book is the final section: “Coming Home to the City.” Here, contributors discuss animals that come and go from the area as well as those that may be stay longer under certain conditions. In “Hardy, Colorful, and Sometimes Annoyingly Loud,” Co-Editor Dave Aftandilian expounds on the love-hate relationship between Hyde Park residents and the area’s burgeoning parakeet population.

“City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness” showcases the city’s natural world in a refreshing and aesthetically pleasing way. The book’s marriage of personal experience with historical record makes for an engaging read. The artwork included is as vibrant and awe-inspiring as the city itself.

–Evan Garcia

Below, an excerpt from "City Creatures."

Tickling the Bellies of the Buffalo

Gavin Van Horn

In metropolitan Chicago, it is difficult to imagine an unbounded, fenceless world of the kind that existed in this region a mere two hundred years ago. Prairie grasses that dominated and defined the area—with wispy stalks brushing the saddles of travelers on horseback, and roots extending ten to fifteen feet into the ground—are now scarce in this Prairie State. Remnants spangle the embankments of railroad right-of-ways, line the pockets of forgotten cemetery edges, and adorn larger forest patches and prairie savannas. Salvaged by accidents of history and the foresight of nineteenth-century Chicago planners, who envisioned an “emerald necklace” circling the city, these urban green spaces account for a great irony: more biodiversity exists in metropolitan Chicago than in rural Illinois, where the soils have largely been repurposed for corn and soybean monocultures—from fencerow to fencerow—to provide forage for livestock, fuel for automobiles, and food for hungry cities near and far.

Dividing up the tallgrass prairie of Illinois was very good for some species but not for others. I think particularly of two animals, bison and wolves, their stories entangled as predator and prey in the dance of the tallgrass prairie’s evolution. Like the prairie flora that co-evolved in their presence, these large mammals were uprooted from places they inhabited for thousands of years.

And yet they have not vanished. They linger on the fringes of memory and in present-day enclosures, evoking future possibilities for a landscape undivided.

***

I pay homage to the defining habitat of Illinois by visiting a restored prairie near Batavia, to stand within shouting distance of one of its more imposing creatures: Bison bison. Most people know this shaggy-maned, one-ton behemoth more familiarly as the buffalo, and there is a small herd in Batavia, cropping the grass an hour’s drive west of Chicago’s Loop.

These bison are residents of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), a high-energy physics facility. Bison and particle physics may seem an odd combination, but Fermilab’s founding director Robert Wilson had a vision for both. Underground would be the realm of quarks and neutrinos, as well as massive particle accelerators that are modern-day marvels of engineering. Aboveground would be still more marvels, but unlike subatomic particles, these could be seen with the naked eye.

Bison were brought to Fermi in 1969. Three years later, Wilson took things further. Persuaded by biologist Bob Betz (a man who described himself as a willing victim of “prairie fever”), Wilson was convinced that representing the indigenous landscape of Illinois was preferable to thousands of acres of suburban lawn. Betz got the green light to spread his prairie enthusiasm, beginning with ten acres above the Fermi accelerator ring. His determination soon attracted others to the cause, and the Fermi prairie restoration has since spread to over 1,200 acres that serve as a diverse mosaic of habitats for Chicagoland wildlife.

Fermilab’s initial group of five bison also expanded over time, and the herd is now managed to hold steady at around twenty-five animals. Some suggestions have been made to join the bison with the prairie restoration. Thus far, however, these massive beasts function only as living symbols of a bygone era. A perimeter of double-fencing divides them from lands they once shaped so extensively, as much to protect the bison as the people who might mistake them for gentle giants.

The role of bison as landscape architects of the prairie is well documented. Among other things, they recycle nutrients, disperse seed, open up patchy areas of increased plant diversity through their grazing, and create wallows that hold water and provide resources and breeding grounds for other prairie species. Their influence on the variety and abundance of prairie species once loomed large. Could bison in Illinois again play such roles? It’s an open question. There isn’t much prairie left.

I lean into the fence and wrap my fingers around the cool metal, watching the Fermilab herd graze at their leisure. I wonder, do they ever sniff at the air in June, when the prairie is afire with colorful blooms, and feel their bodies straining to know what is on the other side of these fences?

Reprinted with permission from City Creatures edited by Gavin Van Horn and Dave Aftandilian published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2015 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Seth Magle secures a camera trap that is used to capture data for Chicago Wildlife Watch. (Courtesy of Urban Wildlife Institute/Lincoln Park Zoo)

How You Can Help Chicago Researchers with a Wild Science Project

Seth Magle secures a camera trap that is used to capture data for Chicago Wildlife Watch. (Courtesy of Urban Wildlife Institute/Lincoln Park Zoo)

How You Can Help Chicago Researchers with a Wild Science Project

A group of local science researchers want your help on a truly wild project. Learn about Chicago Wildlife Watch, and how you can help them better understand the urban ecosystem of Chicago.