Adam Gray took his first steps as a free man in more than 20 years in May. Now in his late 30s, Gray was only 14 years old when he was arrested in 1993 in the arson death of a brother and sister in Brighton Park.

Gray was convicted three years later – in part because investigators relied on flawed forensic evidence that pointed to arson – but also because Gray himself confessed after seven hours of interrogation. Though he later recanted, his confession was introduced at trial and Gray was sentenced to life in prison.

Only after advancements in forensic fire investigations were made years later was Gray’s conviction called into question.

Gray is one of 11 Illinois inmates who has been exonerated so far in 2017. False confessions were involved in some way in six of those cases.

![]()

Innocence Project co-founder Peter Neufeld, in a 2012 “60 Minutes” segment called “Chicago: The False Confession Capital,” described the rate of false confessions in the city in stark terms: “Quite simply, what Cooperstown is to baseball, Chicago is to false confessions. It is the Hall of Fame.”

That statement was met with controversy and blowback at the time – including a letter to CBS from then-Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, who was included in the segment. But a question lingers about the claim: do the numbers back it up?

The National Registry of Exonerations – a project at the University of Michigan that seeks to document and study exoneration cases based on publicly available information – has logged nearly 2,100 wrongful convictions nationwide. Of those, 193 – some 37 percent – came from Illinois. Based on those numbers, Illinois has a false confession rate more than three times higher than the national average of 12 percent.

In fact, of the roughly 250 recorded cases in the U.S. involving a false confession, more than 28 percent come from the state of Illinois. And nearly 1 in 4 come from Cook County.

Map: U.S. exonerations involving false confessions by county, based on data for 245 recorded incidents. Red indicates the highest concentration, followed by yellow and, at the lowest frequency, green.

In the past 25-plus years, there have been 248 recorded exonerations involving false confessions, according to data from The National Registry of Exonerations. Of the 71 that originated in Illinois, 59 came from Cook County.

![]()

“There seemed to be a culture in Chicago of solving cases by confession,” said Maurice Possley, a senior researcher at the National Registry of Exonerations. “And once you got that confession, everything that might have pointed to someone else was considered a red herring or was just discarded.”

It’s almost impossible to talk about exonerations in Illinois, or Chicago, without mentioning Jon Burge. The disgraced former Chicago Police Department detective was responsible for beating, electrocuting and otherwise torturing primarily African-American suspects in the 1970s and ‘80s before his termination in the early ‘90s.

Those cases have led to at least a dozen exonerations, but Karen Daniel, director of Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, stresses that Burge and his subordinates weren’t the only ones who built cases on false confessions.

“In Chicago, in particular, false confessions (are) a huge problem,” she said, “and we are the false confession capital of the country.”

Wrongful convictions

Opened in 1999, NU’s Center on Wrongful Convictions is one of a handful of organizations statewide focused exclusively on getting convicts out of prison. Since its inception, attorneys from the CWC and its sister organization – the Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth – have helped free more than 30 wrongfully convicted men and women.

Those cases include sexual assaults and rapes, assaults and arson, attempted homicides and quadruple murders. All were convicted. All were later released – thanks to DNA, witness recantations or some other evidence.

![]()

Defendants have a right to a speedy trial. But after a conviction, inmates have no right to a hasty follow-up investigation into their innocence.

A Harvard grad and former public defender, Karen Daniel has worked at the center since 2000 and says it receives hundreds of letters from inmates seeking their aid each month.

“A project like mine … tends to take the heavy-duty murder cases, armed robbery, sexual assaults,” she said, “in part because the sentences are longer, and the people keep fighting and fighting and fighting them. And 10, 15, 20 years later, they’re still in prison. And that might be when we get involved.

“I think there is a huge number of wrongful convictions, innocent people being convicted, in the so-called lower-stakes cases – drug cases on down – but the people are in, they get out relatively quickly and they’re not fighting them so much. Those types are harder to fight.”

Perhaps that explains why seven of the 11 exonerations that have occurred so far this year in Illinois involved inmates convicted of murder. In fact, over the past decade, more than 2 out of every 3 exonerations in Illinois have involved murder convictions – a rate nearly twice that of the national average.

“One would think when the stakes are that high – when the sentence is death – those would be the cases where police and prosecutors are the most careful to get it right,” Daniel said. “And yet we kept seeing again and again that they were getting it wrong.”

‘The more we look, the more we find’

Nearly 1 out of every 6 murder exonerations that’s taken place nationwide over the past decade has occurred in Illinois. Of the Prairie State’s 102 total exonerations from 2008 through August 2017, 68 percent of them have been murder cases, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, which each year publishes annual reports detailing the lastest exoneration cases.

Only Texas and New York have freed more wrongfully convicted inmates over the past 10 years than Illinois. But even those states have overturned far fewer murder convictions.

For instance, Texas has more than twice the number of total exonerations over that period (247) as Illinois (102), but only 9 percent of those are for murder cases (23).

Texas, though, remains a unique example in that it has driven up record numbers of exonerations nationwide in recent years with dozens of low-level drug convictions that have been overturned within a single county.

Prior to that spike, Illinois had led the nation in wrongful convictions for decades. Between 1989 and 2011, Illinois recorded 101 exonerations, according to registry data, making it the only state to surpass the century mark. The next highest total was New York with 88.

But even those numbers provide only a snapshot of the full scope of exonerations.

“The number we’ve had for each year has grown,” said Possley, who worked as a criminal justice reporter at the Chicago Tribune for nearly 25 years before joining the registry. “I think in part that’s because courts and prosecutors are more open to these things. And with the creation of things like the Conviction Integrity Units, they’re becoming a little bit more proactive in that area. I also think that because we’ve been out there, people do come to us, and I think we’re just better at finding them.”

Still, he refers to the numbers included in the registry’s annual reports as a “basement figure,” saying nobody knows the full number of exonerations from each of the nation’s 3,000-plus counties. Part of his job is going back and finding cases the registry has missed. Some of the cases added most recently date back to the late 1980s and early 1990s.

“The more we look,” Possley said, “the more we find, so to say.”

‘It takes years’

With thousands of aid requests each year, it’s a difficult process to pick out specific cases to handle, Karen Daniel said.

The Center on Wrongful Convictions is made up of less than a half-dozen attorneys, along with a few additional staff positions and three attorneys handling youth cases. Law students from Northwestern’s Pritzker School of Law also provide a helping hand.

If they feel they have the capacity to take on a case, they’ll first look at the path to a successful exoneration.

Is there a legitimate claim of innocence? Is there a clear legal track forward through the courts or a petition for executive clemency? If the answer to both of those questions is “yes,” then CWC staff begin the investigation into the crime itself and the trial.

But none of this happens quickly.

![]()

Related: How Dana Holland Became the Country’s First Double Exoneree

Related: How Dana Holland Became the Country’s First Double Exoneree

“It takes years,” Daniel said, “in all but in a very small number of cases it’s going to take years. And that’s, to be honest, one of the most frustrating aspects of the case.”

Twelve years, in fact. That’s the average length of time from the point of conviction to a successful exoneration, according to a registry report.

Before a person is convicted of a crime, they have a right to a speedy trial. But after a conviction, inmates have no right to a hasty follow-up investigation into their innocence.

“A lot of times there’s not a whole lot of interest in it,” she said. “The different offices that often deal with these cases – the state’s attorney’s office, the public defender’s office, even the judges – they’re understaffed, and so the cases languish. And it’s very, very frustrating.

“If it’s a case that involves DNA testing and the person is relying on state Police Crime Lab to do the testing, they’re underfunded so even if DNA testing is approved, the case can sit there for a year or more waiting for DNA testing.

“And also it can take a long time to properly investigate an old wrongful conviction case, so I won’t lay it all on those systemic problems.”

![]()

“One would think when the sentence is death – those would be the cases where police and prosecutors are the most careful to get it right.”

—Karen Daniel

Early on, the center would look at cases only if inmates had at least 10 years remaining on their sentences, but that’s no longer their policy. Daniel says they will look at any case, including those where the entire sentence has already been served.

“Even if the person is out of prison, if they have a murder conviction on their back or a sex crime on their back, their life is still hell and there’s still a lot of consequences,” she said, “and then there’s still a lot of value in erasing that if it’s a wrongful conviction.”

A ‘fragile’ system?

It’s been a few years since he left the Tribune, but Possley has no trouble rattling off case after case he covered locally that included a false confession or a wrongful conviction.

There was Daniel Taylor, who gave a false confession to a 1992 double homicide that occurred while he was already in police custody for disorderly conduct. He was convicted anyway and spent 20 years in prison before he was eventually exonerated. There was Eddie Huggins, a 15-year-old who spent more than a year in prison awaiting trial after confessing to stabbing a woman, even though the medical examiner found “no evidence of a stabbing.”

And there was Rolando Cruz, who was on death row when he won an appeal at the state Supreme Court for a third trial only after some turnover on the bench. DNA evidence later proved Cruz was not guilty of a 1983 rape and murder.

“To me, it demonstrated the fragility of the system,” Possley said. “Here is a case where, because one justice retires and another one gets appointed, this case comes back – not because of some new discovery prior to then. I keep using the word fragile, but it’s just, it was a fluke in a way. And for me it demonstrated that maybe some of these cases deserve a closer look.”

In response to the false confession findings, Chicago Police Department spokesman Anthony Guglielmi said: “Judicial and investigative integrity is perhaps one of the most important values for the CPD.” He also referred questioning to the state’s attorney’s office, which did not respond to a request for comment.

In explaining her own “false confession capital” claim, Daniel pointed to the prevalence of the Reid Method of interrogation – a common technique used by officers for decades – which she said can be used to psychologically coerce almost anybody into giving a confession, particularly younger suspects or those with mental handicaps.

The technique was created by John Reid, a former Chicago police officer. And John E. Reid & Associates, which offers nearly a dozen different training programs on the technique to police, military and attorneys, is headquartered in downtown Chicago.

Instead of using violence or intimidation, officers using the Reid Method can break suspects down through hourslong interrogations and a multistep process in which a suspect is repeatedly told the evidence of the case proves their guilt.

Reid & Associates say that when used properly, this interrogation method can be extremely effective. A survey on Reid’s website notes a majority of their clients reported seeing confession rates jump more than 25 percent after using their technique.

But Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates – a consulting and interrogation training firm that’s worked with CPD and other departments across the country – announced earlier this year it will no longer teach the Reid Method after more than 30 years of instruction.

In doing so, the firm noted that almost one-third of U.S. convictions since 1989 overturned through the use of DNA evidence have involved a false confession. Though it said the technique can be effective when used correctly, WZ acknowledged that its improper use, coupled with intense emotional pressure, can have “catastrophic results.”

In response, Reid & Associates said its method is still seen as “the gold standard” by the law enforcement community, adding that the company also works with the Innocence Project to help free wrongfully imprisoned suspects who gave a false confession after the Reid technique was used incorrectly.

Daniel added that it’s hard to say whether there really have been that many more wrongful convictions in Chicago, or if authorities here are just better at rooting them out. And Possley said it’s impossible to tease out a single cause for the number of false confessions.

“It’s easy to say yeah, cause I think just about everybody used the Reid technique,” he said. “I wasn’t there, you know? We didn’t have video tape of interrogations, so it’s hard to know.”

Follow Matt Masterson on Twitter: @ByMattMasterson

Related stories:

15 Men Seek Exoneration in Lawsuit Claiming Chicago Police Corruption

15 Men Seek Exoneration in Lawsuit Claiming Chicago Police Corruption

Sept. 13: More than a dozen residents of the former Ida B. Wells housing project say they were framed and intimidated by a former Chicago Police Department sergeant. Now they are seeking to have their convictions overturned.

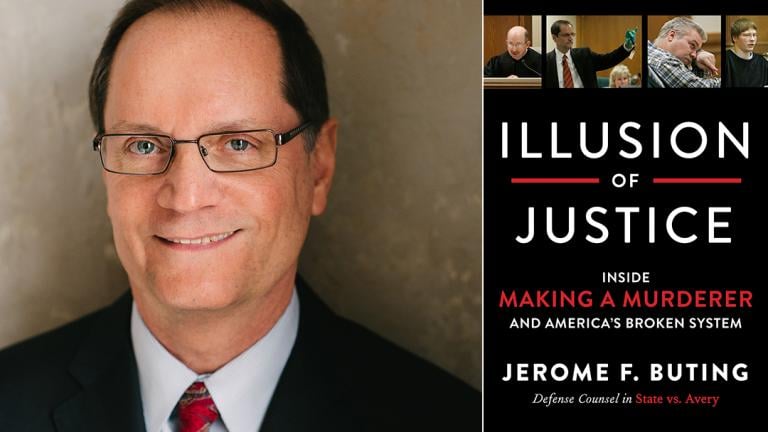

‘Making a Murderer’ Defense Attorney on Broken Justice System

‘Making a Murderer’ Defense Attorney on Broken Justice System

March 20: One of Steven Avery’s defense attorneys from Netflix’s “Making a Murderer” discusses his new book “Illusion of Justice.”

Outgoing Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez Reflects on Office

Outgoing Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez Reflects on Office

Sept. 8, 2016: With only a few months left in office, does Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez wish she had done anything differently? She joins us in discussion.