EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt speaks April 19 after meeting with residents of East Chicago’s lead-contaminated neighborhoods. (Alex Ruppenthal / Chicago Tonight)

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt speaks April 19 after meeting with residents of East Chicago’s lead-contaminated neighborhoods. (Alex Ruppenthal / Chicago Tonight)

Prior to leaving the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Briana Bill worked with small- and medium-sized businesses across the Midwest to prevent pollution, a vital task for an organization charged with defending the environment and public health.

Based out of the EPA’s regional headquarters in Chicago, Bill, a 27-year veteran of the agency, helped provide technical assistance for businesses attempting to conserve energy and water, reduce hazardous waste and identify products that are safer for human health and the environment.

“It was a small but powerful program that saved businesses lots and lots of money,” Bill said.

In March, President Donald Trump released his proposed federal budget for 2018, which included a 31-percent cut to the EPA. Several weeks later, the Washington Post published internal agency documents showing that Trump’s EPA was planning to lay off 25 percent of its employees and eliminate 56 programs.

One of them was the relatively inexpensive Pollution Prevention program that occupied much of Bill’s work, and which accounts for about $12 million of the EPA’s $8.2 billion budget this year.

Although Congress has yet to finalize a budget for 2018, Trump’s proposal signaled to Bill that it might be time to go. After more than two decades with the agency, she retired on Aug. 31.

“I believed there was a very strong chance that within a year, I would not be working with the same job, or with any of my colleagues from the program for that matter,” said Bill, who lives in the western suburbs. “I really wanted to leave on a high note. This was the third time I was actually eligible for a buyout or voluntary retirement. This was the first time I seriously considered it.”

Bill is one of 61 employees who have left the EPA’s Chicago-based Region 5 office between Trump’s inauguration in January and Oct. 17, according to records obtained from the agency through a public records request. None of them have been replaced, as the EPA continues a freeze on external hires.

EPA staff and supporters attend a rally Feb. 6 in support of the agency in downtown Chicago. (Courtesy Sierra Club)

EPA staff and supporters attend a rally Feb. 6 in support of the agency in downtown Chicago. (Courtesy Sierra Club)

At about the time she left the agency, Bill said she and her colleagues should have been planning for the next cycle of pollution prevention grants, issuing requests for proposals and answering questions about the program.

But that work was put on hold, she said, because the agency didn’t know if it would be able to provide the grants to states, which then award the funding to businesses.

“We always knew in every meeting that we went to, every conference call that was held, that once we had a budget, we might not even be doing the program that we were planning for in that meeting,” Bill said about her final months at the agency. “It was definitely a day-to-day morale buster to be there.”

Bill, 55, started as a geologist in the EPA’s groundwater program and then worked in community relations in the agency’s Superfund program, which prioritizes cleanup of hazardous waste sites. In her most recent position, Bill helped manage the EPA’s Federal Green Challenge, which pushes federal agencies to become more environmentally responsible, in addition to coordinating the Pollution Prevention program aimed at businesses.

But she found her work increasingly difficult under Trump-appointed EPA head Scott Pruitt, who sued the agency 14 times as Oklahoma attorney general and even described himself as “a leading advocate against the EPA’s activist agenda.”

“Quite honestly, the core values of this administration are so divergent from my own, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity [for retirement],” Bill said. “I found it difficult to work for an agency with someone who is so disrespectful of what we do and why we do it.”

Since Trump took office, the EPA’s Chicago office has lost 28 employees to voluntary buyouts and early retirements, said Mike Mikulka, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 704, the union representing more than 900 EPA employees in the Chicago regional office and across the Midwest.

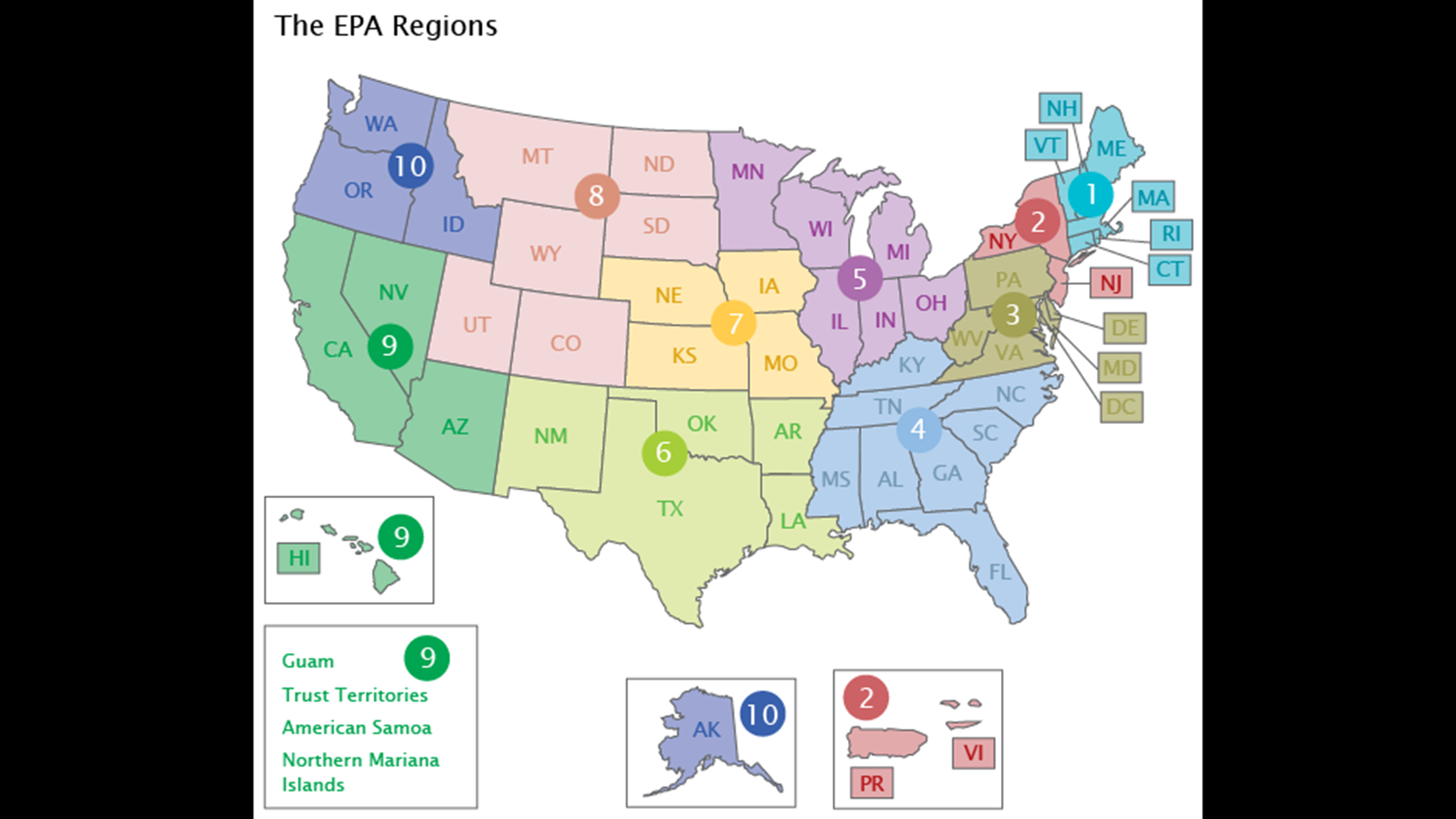

In fact, more Region 5 employees took the buyout this year than any other region except Region 3, which covers five mid-Atlantic states and Washington, D.C., according to data provided by the EPA’s national employee union.

That means 33 employees have left without the incentive of a maximum $25,000 buyout or early retirement.

“That’s even more than I thought,” Mikulka said.

The list of departed employees includes a former acting director of the region’s Water Division; a former director of the Chicago Regional Laboratory, which provides scientific expertise, training and data to support decision-making throughout the region; a former emergency response section chief; two former investigators in the agency’s Superfund program; three attorneys; three engineers; a health physicist; and dozens of other scientific, technical and administrative staff.

All of the employees worked out of the Chicago office, except for a water specialist based in Madison, Wisconsin.

Together, the 61 former employees account for more than 1,000 years of experience and represent nearly 6 percent of the EPA’s Region 5 staff, which coordinates the agency’s work in six states around the Great Lakes.

“I don’t think I remember that many people leaving in such a short period of time,” said John O’Grady, president of the EPA’s national employee union, AFGE Council 238, which represents 9,000 members nationwide.

Current and former employees say the loss of staff is already straining the regional office in Chicago. They say that with fewer support staff, scientists and employees in the field must now also perform administrative tasks, like managing records and filling out time sheets.

East Chicago residents and activists protest EPA head Scott Pruitt's visit April 19 to the city's lead-contaminated neighborhoods. (Alex Ruppenthal / Chicago Tonight)

East Chicago residents and activists protest EPA head Scott Pruitt's visit April 19 to the city's lead-contaminated neighborhoods. (Alex Ruppenthal / Chicago Tonight)

Mikulka said those added responsibilities are especially burdensome for on-scene coordinators at Superfund locations, like the U.S.S. Lead Superfund site in East Chicago, the 322-acre lead-contaminated residential area that more than 1,000 residents were forced to abandon earlier this year.

“The big problem I think is the enforcement support people,” said Charles Gebien, a former Superfund on-scene coordinator who retired on Sept. 30. “[The agency is] very short on them. They’re really the ones who do the legwork. They write the letters, requests for information and notices of liability and that kind of thing. There’s fewer of those now ... so then enforcement slows.”

Gebien, who started at the EPA in 1989, had for the past several years worked part-time as part of a phased retirement. He was working 20 hours per week mentoring his replacement for supervisor of the region’s Indiana emergency response section. He wanted to keep working, he said.

“When they had to make a decision on me, this was at the time there were threats of 35-percent [cuts] to the agency’s budget,” said Gebien, who lives in Glenview. “So they could really not justify keeping me for another year.”

Gebien, 64, said he wants to find another job, though it won’t be at the EPA. He recently applied for a position with the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“Was it different? Yeah,” Gebien said about his final months at the agency. “I don’t think that the employees feel like the president is very sympathetic to environmental matters.”

In addition to fewer support staff, O’Grady said the agency has a smaller number of inspectors taking samples and checking sites for violations. The result, he said, is likely an increased number of businesses operating out of compliance while filling the air and water with high levels of pollutants.

“But we don’t know that because we haven’t gone out in the field,” said O’Grady, who has worked as an environmental scientist in the agency’s Chicago office for nearly 30 years.

Region 5 has also sent 20-22 employees to Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and the EPA’s Emergency Operations Center in Edison, New Jersey, to assist with hurricane response efforts, Mikulka said. Among them is one of the region’s two toxicologists dedicated to Superfund sites, which include the most contaminated sites identified by the agency.

“The hurricane response has been difficult for us because we are supplying resources that would normally be doing our everyday activities to staff those emergencies,” said Mikulka, an environmental engineer, “and so the normal work the people would be doing is put to the side and hence delayed.”

![]()

“I wish the Great Lakes would catch on fire – because then maybe they would get it.”

–John O’Grady, EPA national employee union president

In less than a year, Pruitt’s EPA has not only cut staff but also refused to ban a pesticide shown to cause brain damage in children, halted requirements that would have reduced water pollution from coal-fired power plants and proposed to eliminate the Clean Power Plan, an Obama administration rule to reduce carbon emissions from power plants.

According to media reports, agency decisions are increasingly made by a smaller number of people: Pruitt and a few dozen political appointees. Many of the EPA’s roughly 15,000 career staff have been kept out of the process.

“The agency is acting very uncooperatively these days,” O’Grady said. “When we ask them for information, they only give us information on our bargaining unit. And they won’t even tell us how many managers we have left.”

O’Grady singled out Pruitt’s plan to speed up the agency’s work cleaning up Superfund sites, a pledge that O’Grady notes has yet to be backed up by calls for additional funding or staff.

“I don’t think he knows what he’s talking about,” O’Grady said. “I say that with all due respect, but he doesn’t. It’s clear that these administrators are in place to deconstruct the EPA.”

Along with concerns about the agency as a whole, Bill said she’s worried about the future of the Pollution Prevention program, which she worked on for eight years before retiring.

“I think our whole little program is probably going to be absorbed into another group,” Bill said. “It was the kind of program I would have thought a pro-business [administration] would have liked – it saved businesses money. That one was kind of a head-scratcher to me.”

Staff worried about future of Chicago office

The EPA’s Chicago-based Region 5 office coordinates the agency’s work in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. (EPA)

The EPA’s Chicago-based Region 5 office coordinates the agency’s work in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. (EPA)

At its peak in the late 1990s, the EPA’s Region 5 office had about 1,300 employees, O’Grady said.

In recent years, even as the Obama administration ushered through a series of environmental advancements, agency staffing of support positions declined, said Margaret Herring, a former Superfund investigator who retired on Sept. 2.

Today, O’Grady said Region 5 has just more than 1,000 employees, with no plan in sight to replace recently departed staff.

“We’re losing people, and we’re not hiring any new people,” O’Grady said. “And then as you lose your experienced folks, who’s going to be there to transfer the institutional knowledge?

“I wish the Great Lakes would catch on fire,” O’Grady joked, “because then maybe they would get it.”

Despite reassurances from Pruitt, Region 5 staff are concerned that the Trump administration could close the Chicago office and consolidate the region’s staff with another regional office. O’Grady thinks the administration was at one point considering the idea.

“I don’t think it was ever just a rumor,” he said. “I think they were looking for what the reaction would be, and I think they found there was good bipartisan support for maintaining the regional office here, especially because of the Great Lakes.”

Bill, though, is still worried.

“I think I speak for many people – I don’t believe anything we’ve been told as far as the office closing or not closing,” she said.

O’Grady said the agency might be gearing up for another round of buyouts, with the administration requesting more than $79 million for “additional workforce reshaping” at the agency.

“As much as the younger employees are concerned about their jobs, what you hear more people talk about is, ‘What is this administration going to do to the environment?’” Bill said. “It’s going to take us back decades.”

Contact Alex Ruppenthal: @arupp | [email protected] | (773) 509-5623

Related stories:

Group Plans to Sue EPA’s Pruitt Over East Chicago Coke Plant

Group Plans to Sue EPA’s Pruitt Over East Chicago Coke Plant

Oct. 9: Summary description here. This can be trimmed down as necessary.

Scott Pruitt to East Chicago Residents: Chicago EPA Office Not Closing

Scott Pruitt to East Chicago Residents: Chicago EPA Office Not Closing

April 19: The head of the Environmental Protection Agency told residents in East Chicago on Wednesday that the agency had no plans to close its Chicago office.

EPA Cuts ‘Matter of Life and Death’ for Chicago Communities

EPA Cuts ‘Matter of Life and Death’ for Chicago Communities

March 20: Cuts to the EPA’s budget would affect a disproportionate number of minority and low-income residents in Chicago, experts say.