The recently released Netflix documentary series “This Is a Robbery” explores the twisted story surrounding the theft of 13 pieces of art from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990.

One of the potential paths to recovering the $500 million in stolen artwork involves scientific analysis of paint chips, with microscopic detective work done by a Chicago-based innovator in the field.

After the middle-of-the-night heist, investigators, museum officials and journalists spent years chasing tips that led to dead ends. One lead came to former Boston Herald reporter Tom Mashberg: A petty crook claimed to have one of the stolen works, Rembrandt’s “Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” But Mashberg was no art expert and needed to prove the work was authentic.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee,” 1633.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee,” 1633.

“We sort of thought about paint chips, and I said, ‘Would it be that hard to scrape a little paint off?’” Mashberg says in the docuseries. “Walter McCrone out of Chicago had done a lot of work debunking frauds using an electron microscope.”

Well, not exactly. In fact, McCrone championed a somewhat simpler but no less powerful tool: the polarized light microscope.

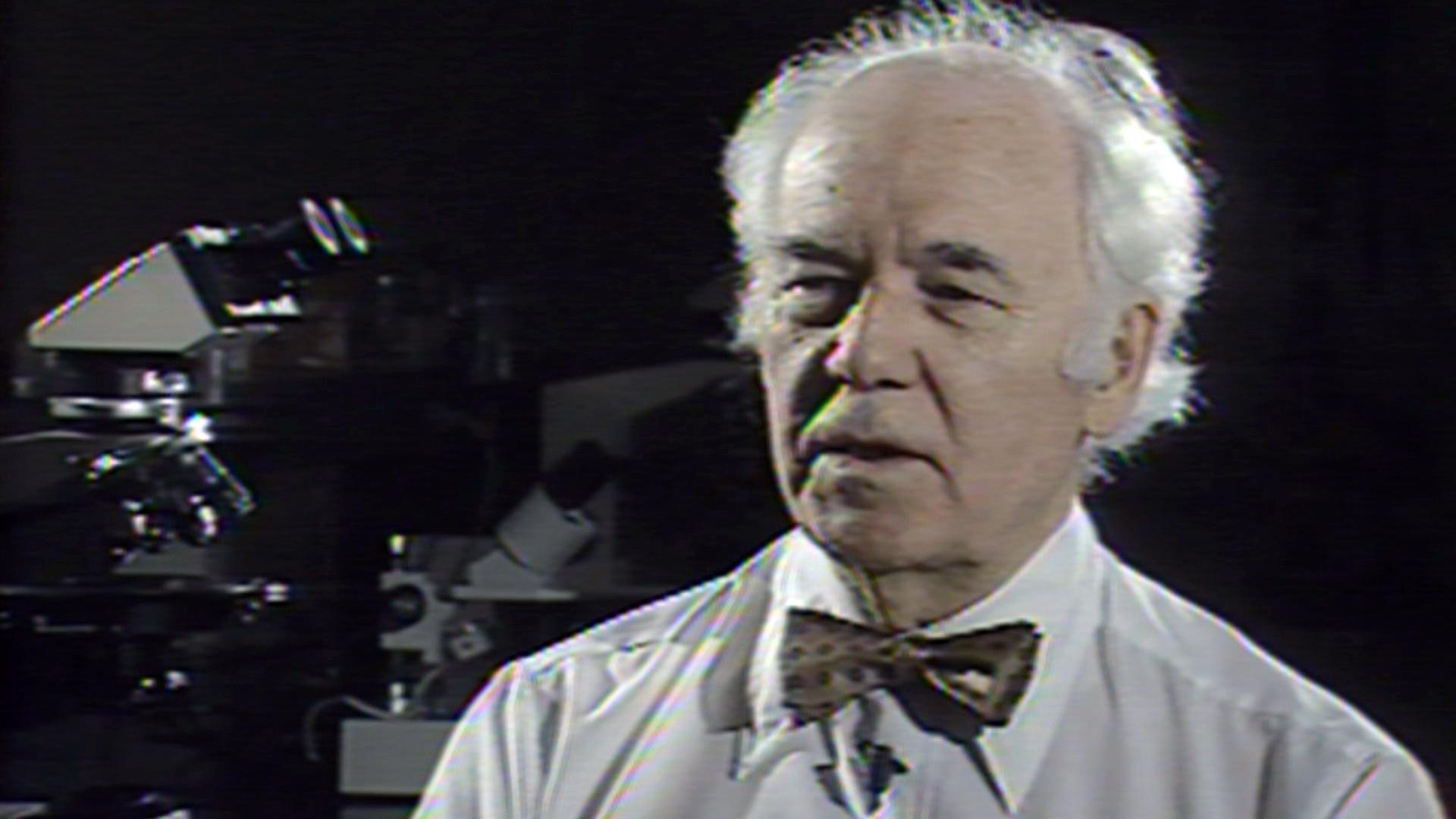

“It’s sort of an underdog,” McCrone told WTTW’s “The New Explorers” in 1990. “People have assumed that it wouldn’t be necessary or even useful anymore because of the big guns. I’m absolutely convinced that we can’t get along without it.”

After studying at Cornell, McCrone took a research job in Chicago in 1944. In 1960, he founded the McCrone Research Institute in Bronzeville. It’s now run by his protégé, Gary Laughlin.

The McCrone Research Institute (WTTW News)

The McCrone Research Institute (WTTW News)

“For all of the years I worked with him, which was the first 17 years of my career, he started his day at 3:30 a.m.,” Laughlin said. “I never saw him leave this building or quit work until after he listened to the news at 6 p.m. each night. Seven days a week.”

The institute is still focused on the mission McCrone started: research, publishing a journal, hosting symposia and teaching intensive courses on how to use a microscope, learning to identify substances’ optical properties like shape, size, color and transparency.

“The students’ range is enormous,” Laughlin said. “They come from every industry, from academia, from the government, virtually any laboratory where a scientist might be working and a microscope might be present.”

Since the institute was founded in 1960, more than 30,000 students from around the country and around the world have come through its doors.

McCrone also gained worldwide notoriety for analyzing hundreds of pieces of artwork and other historical objects. Among the high-profile pieces McCrone put under his microscope was the Shroud of Turin, the alleged burial shroud of Jesus, stained with marks that devotees claimed was blood.

“His conclusion was that there was no blood – that these were a pigment, in fact. Red ochre,” Laughlin said.

Gary Laughlin handles specimens at the McCrone Research Institute in Bronzeville, founded in 1960 by Walter McCrone. (WTTW News)

Gary Laughlin handles specimens at the McCrone Research Institute in Bronzeville, founded in 1960 by Walter McCrone. (WTTW News)

To trained eyes like McCrone’s or Laughlin’s, two colors that might appear identical on canvas look very different under a microscope. Laughlin used French Ultramarine as an example, holding up a vibrant blue paint in a jar.

“This one is synthetic, so this one is modern. The original ultramarine was a crushed up rock, lapis, which is very, very expensive,” Laughlin said. “Because it’s so expensive, nobody uses it today … now, if a forger knew that, they would use the original material. They might even grind it themselves and make their own pigments the way the original artist may have done.”

At the suggestion that a microscopist might make a good forger, Laughlin gave a knowing laugh.

“That’s absolutely true. In fact, Dr. McCrone used to give a talk: ‘What Every Good Forger Should Know’!”

After McCrone used his polarized light microscope to analyze a work, he handed his results to Laughlin to confirm them with an electron microscope – including on the analysis of the alleged Rembrandt featured in “This Is a Robbery.”

“His conclusion right away with that limited palate – he was only given a few chips – was that this certainly could be a Rembrandt,” Laughlin said. “And that was the question that was asked of him,” meaning the paint chips could have come from one of Rembrandt’s contemporaries as well.

A stickler for detail, McCrone even wrote in a correction on his copy of the Boston Herald’s article about his work. Sadly, the paint chips ended up being yet another glimmer of false hope for recovering the stolen art.

McCrone’s work analyzing art may have been exciting, but Laughlin says that was really a side project. The heart of McCrone’s work, teaching people about microscopic analysis, continues today. The pandemic forced a pivot to online learning and a huge drop in enrollment, but things are finally on the upswing.

“You know that there’s this instrument that can do things that you know no other instrument can do, and you want to share that with the world,” Laughlin said.

Walter McCrone appears on WTTW’s “The New Explorers” in 1990. (WTTW News)

Walter McCrone appears on WTTW’s “The New Explorers” in 1990. (WTTW News)

McCrone died in 2002. In his 1990 interview with WTTW, he described his sophisticated work in simple terms.

“What you’re doing is magnifying these little particles up to the size that we normally see macroscopic objects. And if we can recognize all of these things here just at sight, you can do same thing under the microscope. It’s that easy,” McCrone said.

As for that suspected Rembrandt that McCrone analyzed paint chips from? Neither it nor any of the other pieces stolen from the Gardner Museum have been recovered.