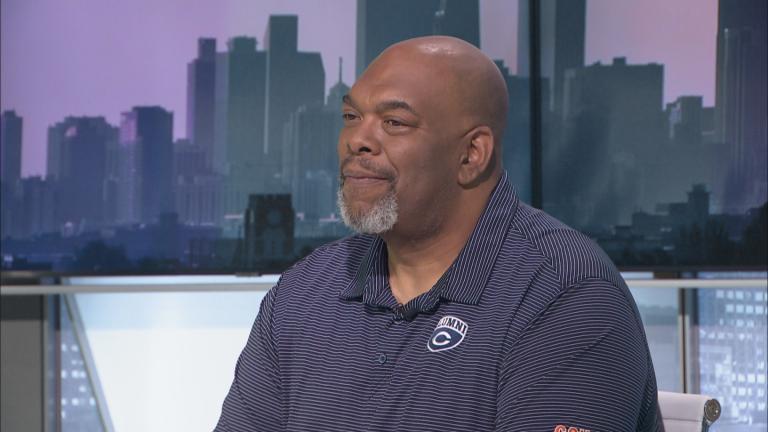

A new book capturing what it was like to grow up in Bronzeville during the 1950s and 60s is the latest installment of our Black Voices Book Club.

“When Blackness was Golden!: Observation from the front line” is a memoir by Pemon Rami. It’s a coming of age story that gives readers a look into the civil rights movement in Chicago and an era when Black culture and excellence were on the rise.

“It’s a retrospective. It’s a look back at an era in which we were more interested in the development of the group than the individual,” said Rami. “You saw the proliferation of organizations like the African American Patrolmen’s League, the Black psychologists. Almost every school had an organization that was comprised of parents, concerned parents that were working in the schools, you had institutions around the city that were responsible for creating environments in which people could have discussions to eliminate violence.”

Rami said he named his memoir “When Blackness was Golden!” to describe the rise of Black culture during that time period.

“During that period of time, the 1950s of course is when Emmett Till was killed and there were a number of lynchings during that period of time, but when you roll into the 60s, you get another different sense, you get a sense of manhood, you get a sense of people understanding of their relationship to Africa. You get people appreciating their natural beauty and the natural hair,” said Rami. “When I said that it was golden, it was more about how we felt about ourselves, our commitment, even the singers and the musicians and the artists and the filmmakers were geared in to developing work that was uplifting that would restore us to our traditional greatness.”

An excerpt from “When Blackness was Golden!: Observation from the front line” a memoir by Pemon Rami

“Don’t allow yourself to believe your natural beauty requires augmentation to change you into a diminished version of another cultural group.”

When Maséqua and I met, I had already begun working with Jim Harvey on opening the Umoja Black Student Center at 251 East Thirty-Ninth Street, directly across from Wendell Phillips High School. By the early '70s, AfroAmerican student movements were springing to life everywhere—on campuses, in high schools, and in communities. Students were affirming new demands and priorities. The birth and direction of the Umoja Black Student Center needed young leadership, and I gladly took on one of those roles.

I had contacts at many of the high schools and colleges citywide through my performing company, which made recruitment easier. Umoja opened as a cultural center and home for Black students.

The Umoja Black Student Center was governed by a central committee with twelve members, including me, who decided on the efforts and philosophy of the organization as well as which activities we would become involved with. I was the coordinator of the Black Students for Defense (one of the subgroups) of the Afro-American Student Association.

The Umoja Black Student Center reflected this multicultural programming. It was the home for African American teens and adults in Chicago trying to find themselves.

Black History, culture, manhood, womanhood, Swahili, karate, and self defense classes were among our offerings.

In November 1967, Englewood High School became the epicenter of our efforts when Owen Lawson, a teacher who insisted on including Black history in his lesson plans, was dismissed. We met with the students, helped them develop their strategies, and even cut or styled their hair for those who wanted to wear their hair natural. Englewood students held walkouts and protests but despite their efforts, Owen was not reinstated. Lawson's struggle demonstrated the need for more Black control of our schools and, more specifically, our education.

Broadcast veteran Harold Lee Rush, one of the student leaders at Englewood during that time, became a good friend and joined my acting group.

One of my personal objectives while performing at various schools and community functions was to recruit members and to conjoin the variety of school organizations to find leaders who could help us organize people. I was able to enlist many individuals to join our efforts, which impacted the rest of the movement. I grew to understand the skills and work of activists and the powerful role they played in any community, city, or country.

The third Black Power conference was held at the historic Church of the Advocate in the heart of North Philadelphia from Wednesday, August 28 to Sunday, September 1, 1968. The conference drew over 4,000 people, far exceeding the building's capacity.

The conference theme was "Black self-determination and unity through direct action." Attendees included Max Stanford, Queen Mother Moore, Maulana Karenga, Amiri Baraka, Jesse Jackson, Whitney Young, Nathan Hare, John Conyers, and Rosa Parks, to name a few. We organized ten workshops around politics, education, culture, history, economics, reparations, Black women community organizing, religion, communication, and education.

Maséqua and I co-chaired the high school student workshop. One of the defined outcomes was a plan to return to our respective cities and schools to organize a movement to create major changes needed in the educational system. In many ways, the current Black Lives Matter movement is the contemporary version of our movement in terms of youth leading the action in the streets.

While I was in Philadelphia for the conference on Thursday, August 29, five members of the emergency consultative committee held a midnight meeting at the Umoja Center to discuss the results of action taken around the Democratic Convention and the condition of the police state in Chicago. During the meeting, multiple shots were fired into the building. Members scrambled for their lives. The chairman of the Umoja Center, Jim Harvey, remarked, "The attack was an extension of the racist war on Black students seeking self-determination for all Black people."

The Chicago Student Movement

When I returned to Chicago, we learned of the shooting at the center and that one of our members had been murdered a few days later. I immediately began reaching out to other students and organizing small gatherings to share the conference outcomes and events. In the fall of 1968, student protests began at Austin and Harrison High Schools. We saw these protests as opportunities to move forward.

On Sunday, October 13, 1968, I organized a final meeting before the boycott of twenty-five representatives from more than thirteen Chicago high schools at the Umoja Black Student Center. The purpose of the meeting was to consolidate growing protests at numerous high schools and to form the Black Students for Defense subgroup of the Afro-American Student Organization to organize our collective demands and demonstrations. I was selected coordinator.

High schools represented included Calumet, Chicago Vocational, Dunbar, DuSable, Englewood, Harlan, Harrison, Lindblom, Marshall, Parker, Wendell Phillips, Simeon, and South Shore. During the meeting, we set plans into motion for a citywide school boycott and distributed copies of the manifesto containing twelve demands, most of which were developed during the student workshop at the National Black Power conference. We attended a Me addressing the press at the CPS mock funeral with Maséqua and her brother Relman ST-11006287-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum meeting at the Board of Education to submit our series of demands that we called the Black Manifesto.

Black Manifesto Demands

1. Complete courses in Black history

2. Inclusion in all courses the contributions of Black persons

3. Black administration in schools in the Black communities

4. More technical and vocational training

5. More Black teachers

6. Repair of school buildings in Black communities

7. Holidays on the birthdays of such Black heroes as Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, W. E. B. DuBois, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

8. Insurance for athletes

9. Use of Black businesses to supply class photos and rings in Black schools

10. Better cafeteria food

11. Military training relevant to Black people's needs

12. More required homework to challenge Black students When our demands were not seriously addressed, we set the boycotts in motion.

The first citywide boycott took place on Monday, October 14, 1968. According to published reports, between 27,000 and 35,000 students stayed out of school. We held a rally at the Affro-Arts Theatre and then marched to Washington Park, where I addressed the large crowd along with Jim Harvey, Victor Adams, and Russ Meeks. We decided to only boycott school on Mondays because we wanted to demonstrate we were still interested in receiving an education.