Video: Sarah Wetmore, acting president of the Civic Federation, appeared on “Chicago Tonight” to discuss the group’s new report detailing five major fiscal challenges facing Chicago. (Produced by Eunice Alpasan)

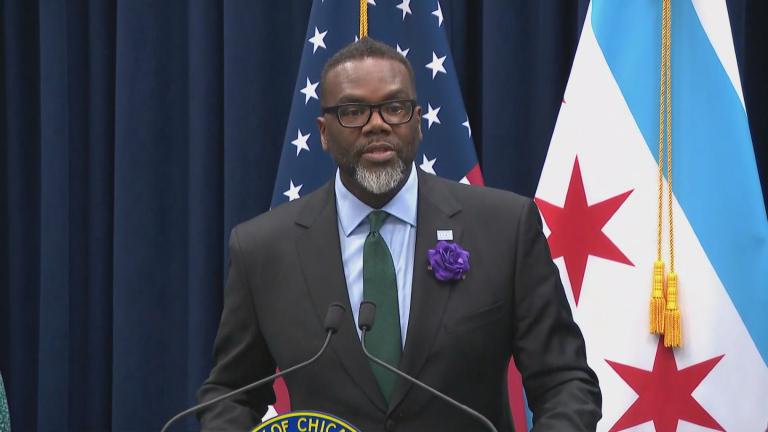

The working group formed by Mayor Brandon Johnson to tackle Chicago’s acutely underfunded pensions is set to meet for the first time this week to confront one of the major fiscal challenges facing Chicago’s new leader.

The group of state lawmakers, city officials and union leaders faces a daunting task, complicated by Johnson’s campaign promise not to raise Chicagoans’ property taxes, the city’s largest source of revenue and the most effective way for city officials to raise revenue and ensure expenses do not outstrip costs.

Johnson’s vow not to raise property taxes, which he said were already “painfully high,” was at the heart of his financial platform during the campaign. He also promised to reverse former Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s plan to automatically hike property taxes to keep pace with inflation.

“We can make Chicago safer, grow Chicago businesses, create good jobs, strengthen public schools for all of our kids, protect our environment, improve mental health, and fix our broken transportation system — without raising property taxes,” according to Johnson’s campaign platform.

If Johnson wasn’t fully aware of the formidable challenge facing the group, the mayor got another reminder from the Civic Federation, a nonpartisan fiscal watchdog, which called the city’s “enormous pension shortfall” one of five major fiscal challenges facing Johnson in a report released Wednesday.

The city’s finances will continue to be pinched by soaring pension payments, as the city complies with a state law that requires two of Chicago’s funds be funded at a 90% level by 2055 and the other two by 2058, ensuring they can pay benefits to employees as they retire.

“The high unfunded liability has burdened the city for years and continues to be a concern because pension obligations will continue to put pressure on the city’s budget and constrain its finances,” according to the Civic Federation.

Jason Lee, a senior adviser to Johnson, told WTTW News the mayor was committed to dealing with the structural deficit that has left Chicago’s four pension funds less than 24% funded, combined, while fulfilling his campaign promises to invest in Chicago and its people.

“The mayor has been very clear that he will not do that off the backs of working people, who have borne a disproportionate burden in years past,” Lee said.

The Civic Federation’s report echoes Johnson’s call for “additional stable sources of funding” to bridge the pension funding gap.

Johnson campaigned on a platform that endorsed plans to raise $800 million in taxes from a host of sources, including by raising taxes on big firms for each Chicagoan they employ and on the sale of high-value properties.

Johnson has been pleased by the willingness of state and federal officials to collaborate on potential solutions, and has gotten “good ideas” from the business community, Lee said.

The Civic Federation warned Johnson against thinking Chicago hit the jackpot with the imminent opening of the city’s first casino — that revenue will not be stable enough for the city to count on as a long-term solution to its pension woes, according to the group’s report.

A temporary casino is set to open in the Medinah Temple this summer, with the casino and resort planned for the current River West home of the Chicago Tribune set to open in 2026. Officials expect that to generate as much as $200 million annually, which state law earmarks for police and fire pensions.

“Much more will need to be done in the future and the mayor and City Council will need to make difficult decisions, including additional budgetary cuts, savings and possibly even more revenue,” according to the Civic Federation.

In all, Chicago owes $33.7 billion to its four employee pension funds representing police officers, firefighters, municipal employees and laborers, according to the 2021 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report.

The 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report is set to be released in the next two weeks, giving officials an updated and comprehensive look at Chicago’s financial condition at the tail-end of the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, which triggered an economic catastrophe by shutting down schools and businessness.

At the same time, more than $2 billion in federal relief helped buoy the city’s finances during and after the pandemic — but those funds must be earmarked by the end of 2024, and spent by the end of 2026.

Managing the city’s finances after all of the federal relief is spent also presents a major fiscal challenge to Johnson, according to the Civic Federation report. The 2025 budgets of the Chicago Transit Authority and the Chicago Public Schools will be especially hard hit by the end of federal COVID-19 relief, records show.

Not-So-Rosy Outlook

The renewed attention to Chicago’s underfunded pensions belies the narrative the Lightfoot administration sought to establish as she left office that she had left Chicago’s finances on much firmer footing than she found them by climbing the so-called pension ramp to comply with state law.

Between 2019 and 2023, the city of Chicago paid an additional $1.3 billion into to its four pension funds — without adding to the city’s already massive debt burden or cutting services, an accomplishment many financial experts considered impossible.

Lightfoot also made the first-ever additional payment toward the city’s pension debt, using $242 million from an unanticipated surplus in 2021. That move won plaudits from Wall Street ratings agencies.

Before she left office, Lightfoot signed an executive order that sought to tie Johnson’s hands and reserve anticipated surpluses from the 2022 and 2023 budgets to make additional pension payments. Johnson’s campaign platform acknowledged the need to spend $250 million more than required to keep the city’s pension debt from growing, and he did not reverse Lightfoot’s executive order during his first month in office.

However, Johnson did issue an executive order on Friday pushing back the deadline for him to release the city’s official forecast for the 2024 budget to Sept. 30, a month later than usual. That will kick off budget season at City Hall, with Johnson due to release his proposed spending plan by Oct. 31. The City Council must approve a budget by the end of the year.

Johnson tapped Annette C.M. Guzman to lead that effort as the city’s budget director. Guzman served as Cook County’s budget director from January 2020 to May of this year.

The City Council’s Budget Committee will get its first chance to publicly quiz Guzman at 2 p.m. Tuesday, when she is set to appear for her confirmation hearing.

Police Pension Fix At Issue

Johnson announced the formation of the working group in the waning days of the General Assembly’s spring session, amid intense debate over a measure that would boost the annual cost-of-living increase added to payments made to retired police officers.

Before leaving office, Lightfoot urged lawmakers to reject that proposal, saying it would add $55 million annually to the city’s pension bills. Johnson prevailed on lawmakers to delay a vote on the measure pushed by the Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge 7, until he could get his financial team in place and dig into the city’s balance sheets.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed a similar measure into law in April 2021, ensuring that all retired Chicago firefighters get a 3% annual cost-of-living increase, regardless of whether they were born before or after Jan. 1, 1966.

Even though the Firemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago calls for those born after that cutoff date to get annual cost-of-living increases of just 1.5%, the city and firefighters frequently moved that date, and all firefighters got the 3% annual boost, avoiding conflict between the city and Chicago Fire Department Firefighters Union, Local 2.

Lightfoot vehemently objected to that bill, sponsored by state Sen. Rob Martwick (D-Chicago), saying it would it add between $18 million and $30 million to the city’s annual bill to fund firefighters’ pensions.

But Martwick, who also sponsored the bill that failed to pass this spring, has long urged the city must confront the true costs of its pension obligations if it is ever going to actually right its financial ship.

The pension fix for police officers is likely to be at the top of lawmakers’ agenda when they return in the fall for veto session, which gives the working group just a few months to craft a solution to the thorny problem laid out by Johnson.

“The working group's mission is to find workable solutions with sustainable funding sources to ensure retirement security and taxpayer relief,” Johnson said in a statement that was perhaps most notable for what it did not contain, including once perennial demands for “structural reform” or cuts to pension benefits.

Lee said that is based on Johnson’s “lived experience,” as a former member of the Chicago Teachers Union who worked as a teacher and and an organizer.

“He knows what it is like,” Lee said, to “choose to serve” and accept a lower salary in return for retirement security. “Honoring that commitment is nonnegotiable.”

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]