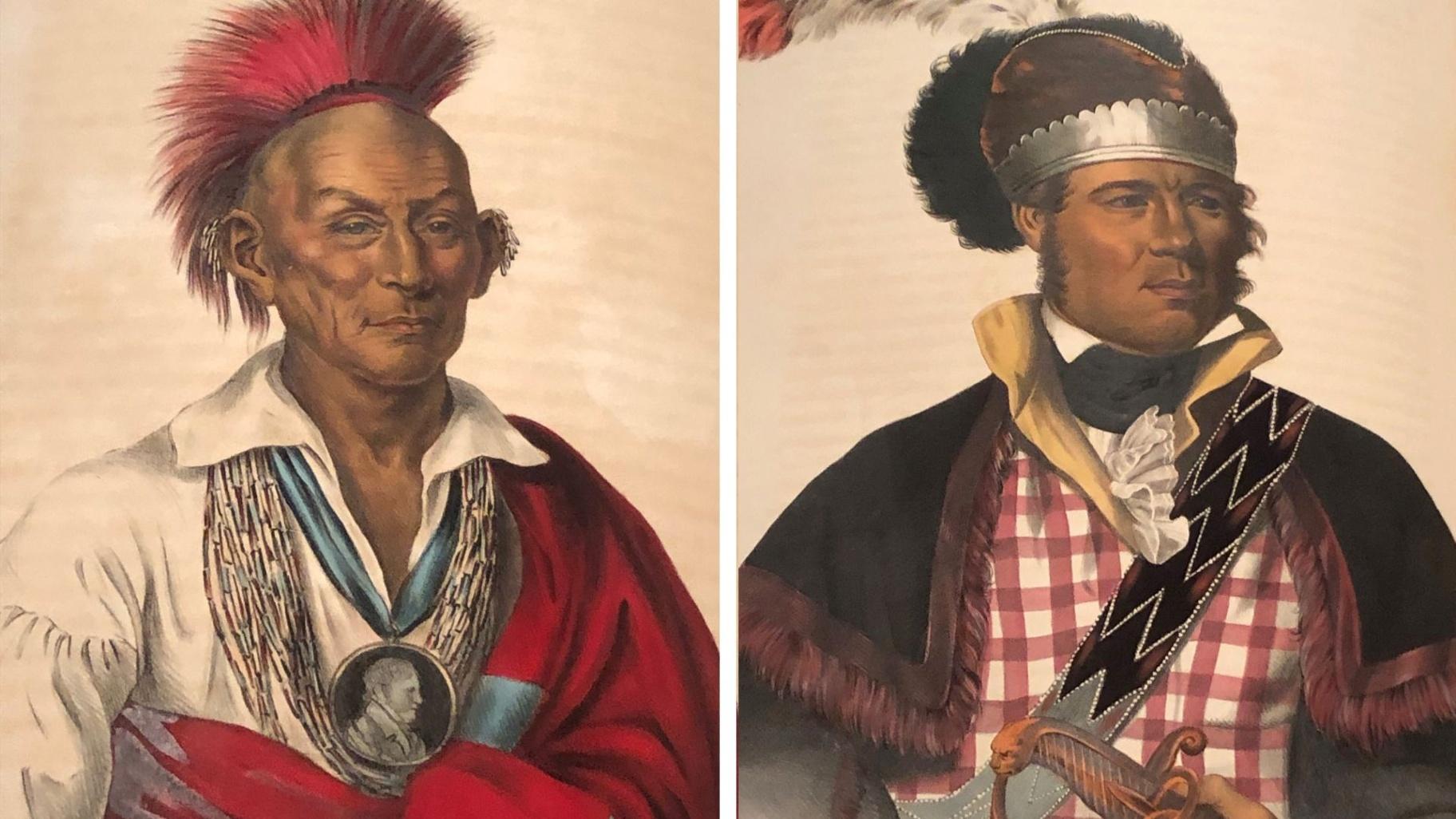

Left: Black Hawk (Sauk). Right: M’intosh (Creek). Both images are on display in “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” at the Newberry Library. (Marc Vitali / WTTW News)

Left: Black Hawk (Sauk). Right: M’intosh (Creek). Both images are on display in “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” at the Newberry Library. (Marc Vitali / WTTW News)

“Antiques Roadshow” fans visiting the Newberry Library’s new exhibition may experience a sense of deja vu.

On view are selections from “History of the Indian Tribes of North America,” a set of early 19th century books rich with imagery.

When the “Roadshow” featured this three-volume collection in 2020, a first-edition set of the books was appraised at $90,000.

“It’s exciting to highlight this new acquisition,” curator of Americana Will Hansen told WTTW News. “It’s one of the best-known books from the pre-Civil War era in the United States.”

It’s also one of the earliest and best records of what Indigenous people, including Seneca and Black Hawk, actually looked like.

Originally published between 1837 and 1844, the books are known by curators and collectors as among the finest examples of 19th century American lithography. The volumes contain 120 prints, a select group of which are on view at the Newberry.

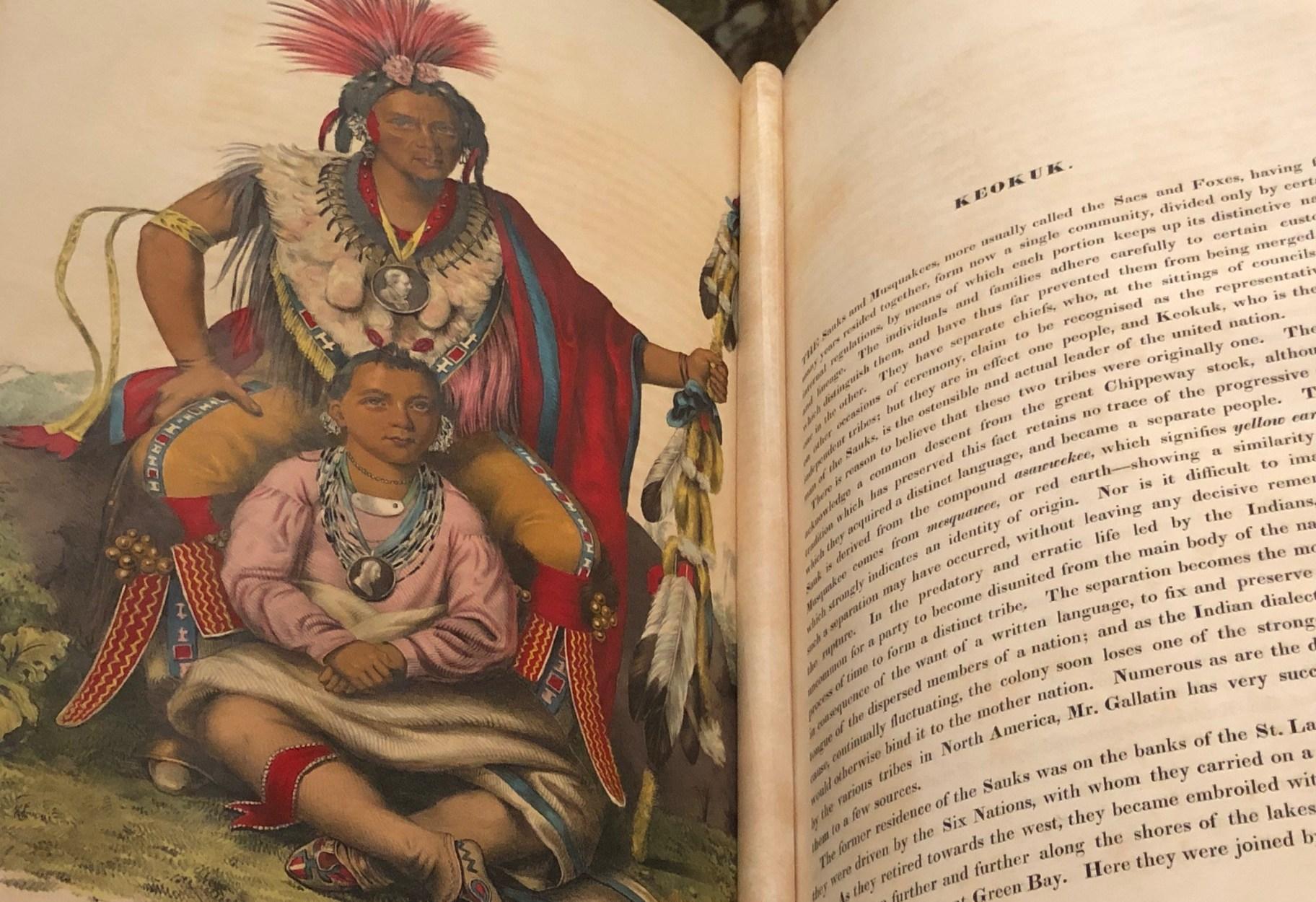

Keokuk (Sauk) father and son portrait. The image is on display in “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” at the Newberry Library. (Marc Vitali / WTTW News)

Keokuk (Sauk) father and son portrait. The image is on display in “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” at the Newberry Library. (Marc Vitali / WTTW News)

The images come from an era of dispossession when Indigenous leaders visited Washington, D.C., to sign treaties. The prints are copies of oil paintings made when delegates of various tribes sat for portraits. The original canvases were lost in a catastrophic fire at the Smithsonian in 1865.

The books were made in the manner of the Audubon folios. Pamphlets called fascicles were periodically printed and mailed to subscribers. They were intended to be reassembled into permanent bindings. The images are accompanied by biographies that Hansen said can be condescending in tone.

According to Hansen, the authors “knew a lot of people on what was the Western frontier of the U.S. at the time, this part of the world (the Midwest). They drew biographies mostly from White European contacts, but they didn’t have interviews with the peoples themselves. So there are inaccuracies and condescending tones and all the kinds of things you’d expect to see in Whites writing about Indigenous people in the 1830s.”

“That being said,” Hansen added, “the authors believed that what was happening to the Indigenous people at the time — the removal from their lands to lands west of the Mississippi — was a great injustice. Some of the impetus for this was to create an accurate record of the people as they were leaving those lands. The authors were mostly sympathetic, if kind of patronizing and espousing a view that the Indigenous people were going to just vanish eventually.”

Tshusick (Ojibwe woman). The image is on display in “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” at the Newberry Library. (Wikimedia)

Tshusick (Ojibwe woman). The image is on display in “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” at the Newberry Library. (Wikimedia)

The books were created and published by Thomas McKenney and James Hall, who hired the renowned American artist Charles Bird King to paint the portraits.

McKenney was a man of contradictions, a Quaker who worked in the Department of War. As superintendent of Indian affairs, he supported the notorious Indian Removal Act of 1830. Yet McKenney also said Indigenous people should be “looked upon as human beings, having bodies and souls like ours.” He wanted to preserve in the archives of the U.S. government “whatever of the aboriginal man can be rescued from the destruction which awaits his race.”

Hansen reminds visitors that these volumes are a small part of the Newberry’s “huge collection related to American Indian studies and Indigenous studies, which is one of the best books and manuscripts collections on the topic in the world. So there’s lots more to explore here.”

If you visit this gem of an exhibition before Dec. 30, don’t miss the show in the next gallery. “Seeing Race Before Race” explores the roots of racial concepts from the Middle Ages to 1800 and includes a copy of the only known portrait of Pocahontas. The last day for that illuminating exhibit is Dec. 29.

The exhibition “Indigenous Portraits Unbound” is free at the Newberry Library through March 30, 2024.