When Maria Puga looks through pictures of her youngest son, Kobe Puga, who was killed on Oct. 14, 2023, she is reminded of how he lived.

“The person who killed Kobe didn’t know who he killed because Kobe was a fundamental piece to our family,” she said. “He was a beautiful person, and I keep questioning why they harmed my son.”

Puga remembers her son as a car enthusiast who often spent hours in the garage taking cars apart and rebuilding them.

“I took care of my son so much for someone to just take his life in one moment,” she said.

The 21-year-old was killed in a drive-by shooting around midnight near 19th and Paulina streets in Pilsen, police said.

“He was home that day. He took a shower and we started to have a conversation in the living room,” Puga recalls. “He told us he was going to deliver a car piece and then was going to go eat.”

He never made it back home. As the case remains open, his family is left to cope with the trauma.

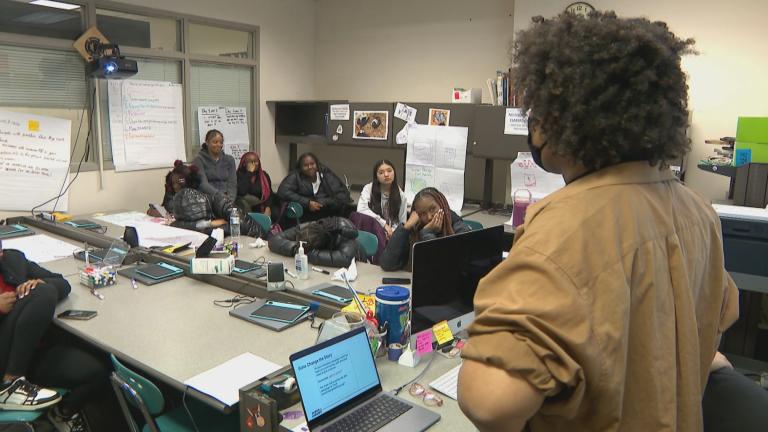

That’s a process Kathryn Bocanegra, an assistant professor at University of Illinois Chicago’s Jane Addams College of Social Work, has dedicated her work to understanding.

“Overwhelmingly what survivors want are answers,” Bocanegra said. “Why my child? Why my husband? Why my loved one? Why did that bullet hit the person I love? What was the motive behind it? … Families want answers and accountability and they have to rely on a process they can’t control.”

Bocanegra has worked alongside families who have lost loved ones to gun violence.

“Establishing safety is one of the hardest things for a family who lost loved ones to violence,” Bocanegra said. “I’ll say the second part is going through the legal process of the homicide investigation.”

Over the years, the Chicago Police Department’s homicide clearance rates have declined. In most cases, clearing a crime means police have enough evidence to prosecute and charge at least one suspect.

In 2014, nearly 40% of cases were closed for homicides involving firearms. Last year, that number was close to 20%.

Eugene Roy, the department’s retired chief of detectives, says several factors go into investigating shootings and homicides.

“To start off, there’s systemic problems,” Roy said. “One of the systemic problems is the fact the Chicago Police Department is only assigned 7% of its sworn police officers as detectives. Now that’s being compared to New York City and Los Angeles, which both have 14-15% of their sworn officers assigned as detectives.”

Another critical factor that Roy says affects the pace of investigations is not having enough police officers.

“Now the police department are 1,700 hundred short of where it was four years ago,” Roy said. “That’s a net loss, not 1,700 retirements. Now because of the diminished manpower in the districts, these officers in the beats are going from call to call, which cuts down on their time to communicate with people in the community.”

The community sometimes plays a big part in solving a case. Roy says people who witness a homicide are often reluctant to talk to the police because Cook County does not have a witness protection program.

For years, city leaders have called for one. Bocanegra says it would be an essential tool for detectives and families seeking justice.

“The legislation has passed to fund the witness protection program in the state level and now there is a grant available for local law enforcement agencies to be able to apply for those funds to implement a witness protection program,” Bocanegra said. “The third step is educating the public on this opportunity. We need to train law enforcement agencies how to work with witnesses so those funds can be used to ensure their protection and cooperation in an investigation.”

It’s been nearly five months since Kobe Puga died, and despite a $15,000 reward offered for information, the family is still waiting for answers.

“I want them to get the person who killed my son. It won’t return him, but I might get some peace,” said Maria Puga. “I’m suffering right now while the person responsible is out there living their lives.”

Bocanegra says in her experience, the path to obtain justice is different for every family.

“Justice involves system change and I heard this from many family members is that justice involves changing the way detectives interact with families, that prosecutor talk to families that schools respond to at-risk youth and more broadly how people in the community can take care of each other,” she said.

“Long live Kobe” stickers with an image of a car can be seen along 19th Street — a reminder of a day that Maria Puga says changed her family’s life forever.

“I feel so frustrated not understanding how they took my sons life away with so many dreams,” she said. “I was left destroyed. The entire family is.”

A Safer City is supported, in part, by the Sue Ling Gin Foundation Initiative for Reducing Violence in Chicago.