The Field Museum’s rare copy of John J. Audubon’s “Birds of America” is now on public view. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum’s rare copy of John J. Audubon’s “Birds of America” is now on public view. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

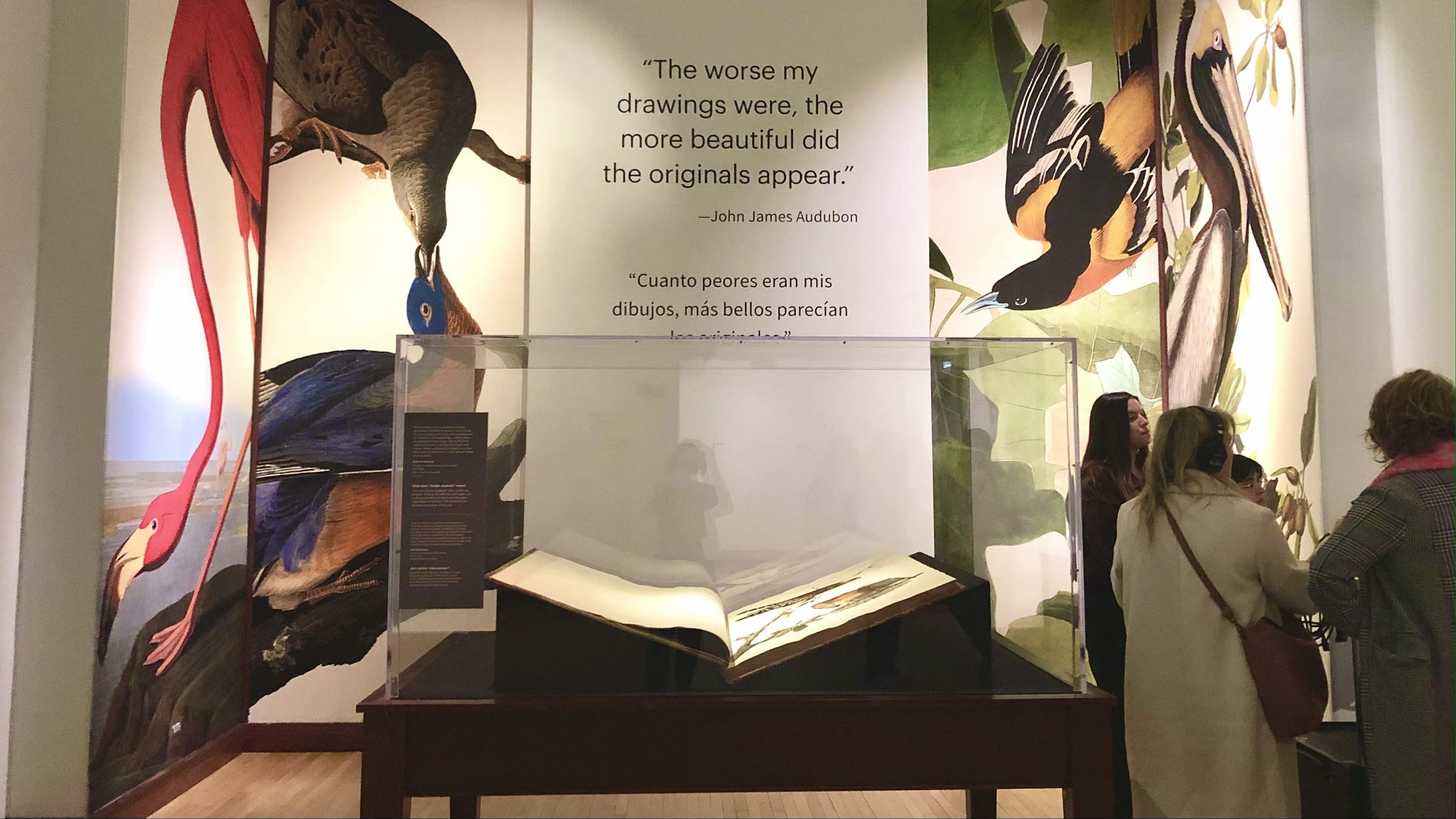

For the first time in five years, the Field Museum has dusted off its rare copy of John J. Audubon’s seminal “Birds of America” and placed it on public display.

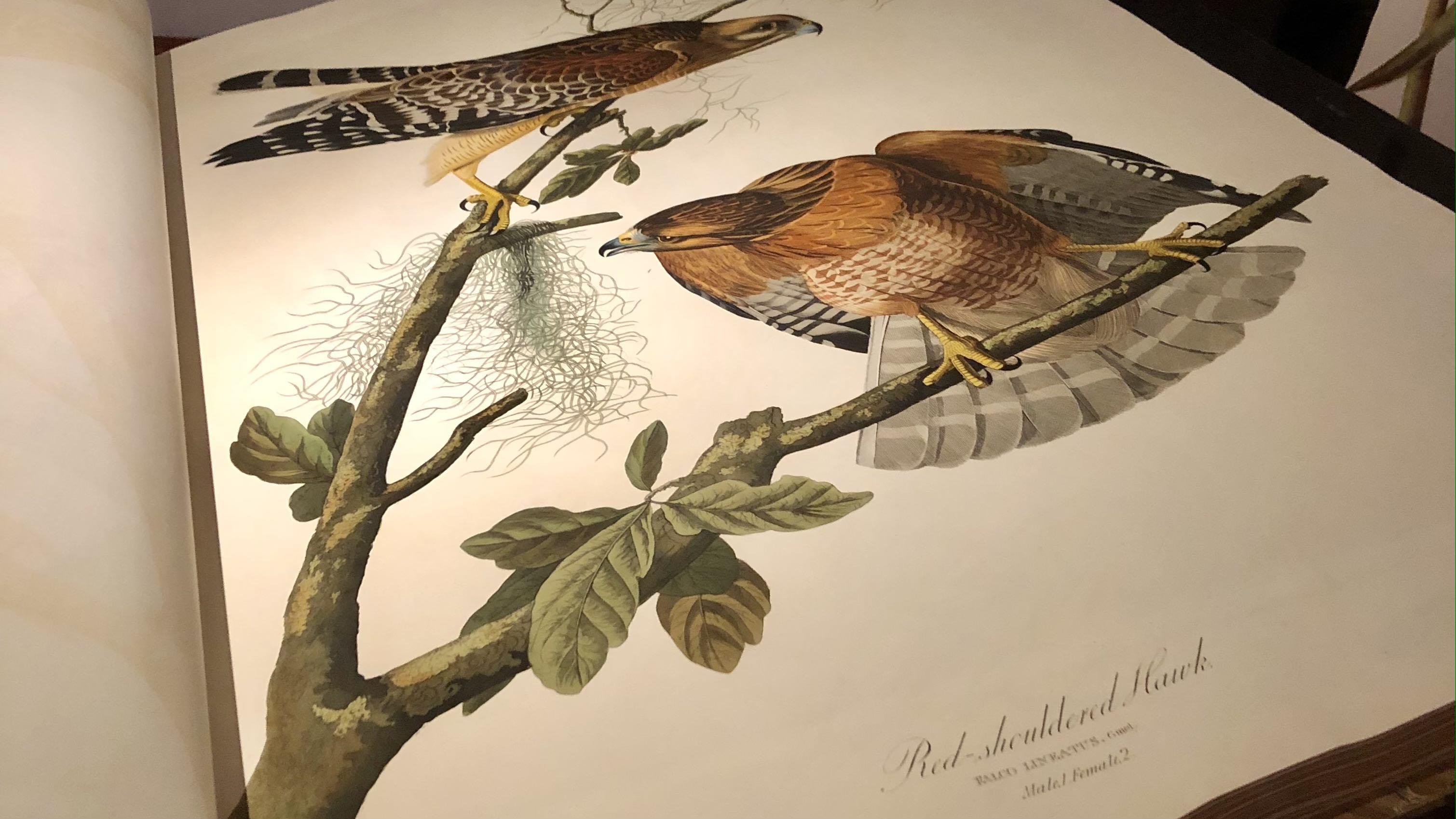

Only 120 complete sets of Audubon’s 435 exquisite, hand-colored engravings are known to exist. Museum staff will turn to a new page once per month for the next two years, giving visitors a chance to view the paintings in their full-resolution glory, printed on what was, in 1838, the largest paper available — roughly 3 feet by 2 feet per sheet, a size known as “double elephant folio.”

“I don’t think we understand how much went into that compared with what we can do now — just snap a picture,” said Doug Stotz, senior conservation ecologist at the Field. “In the time of AI, it’s the real thing.”

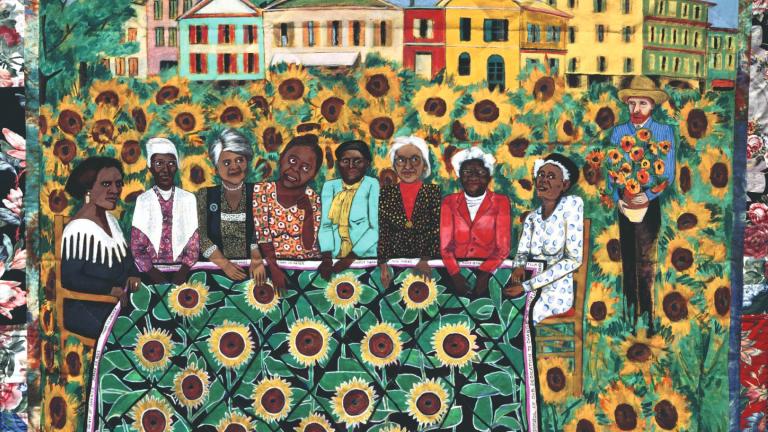

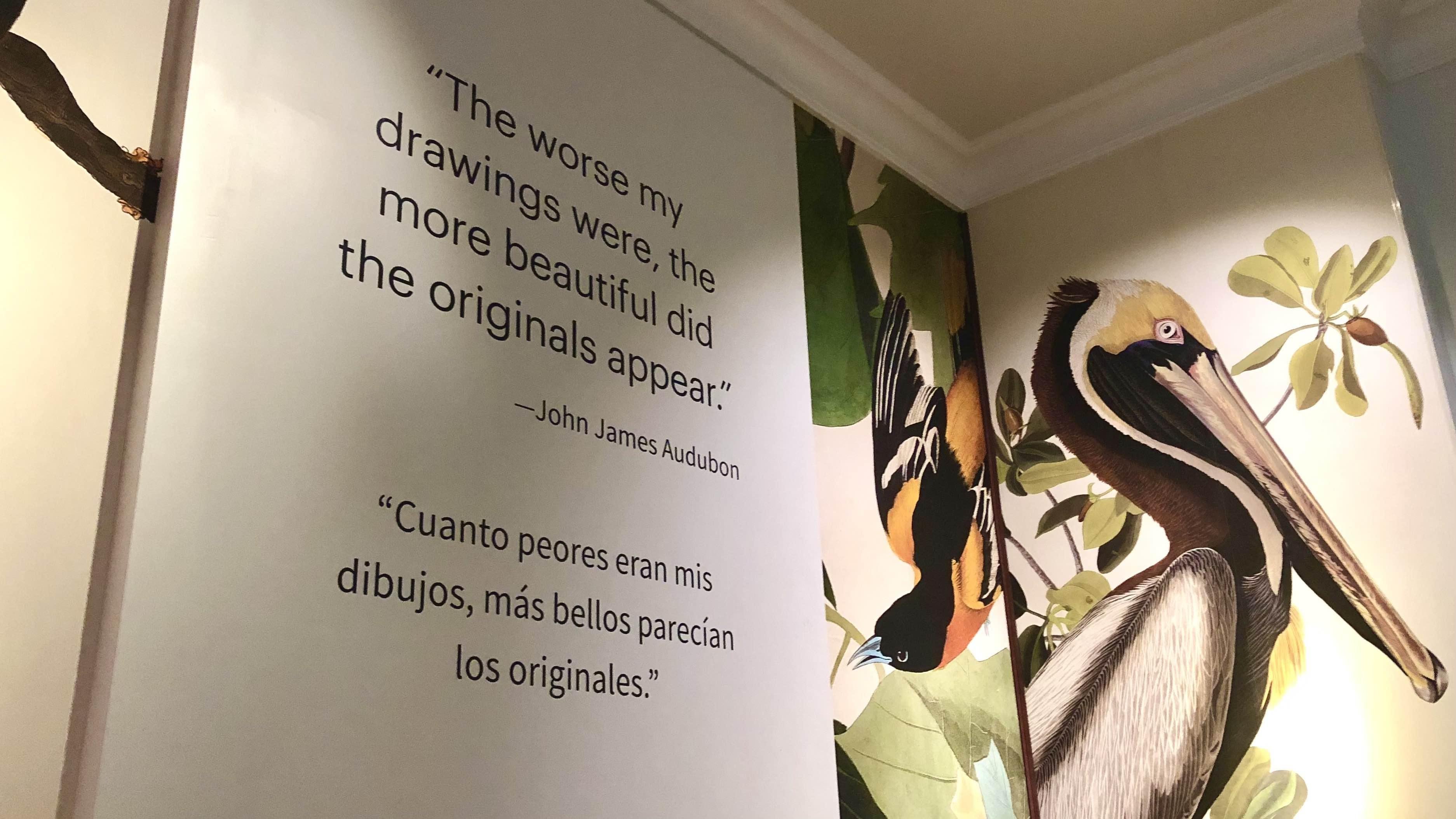

Towering floor-to-ceiling images, replicating some of Audubon’s lush paintings, dominate each corner of the exhibit space, the T. Kimball and Nancy N. Brooker Gallery on the museum’s second floor. A slideshow of additional illustrations is projected on the wall, with piped-in recordings of birdsong providing a fitting soundtrack.

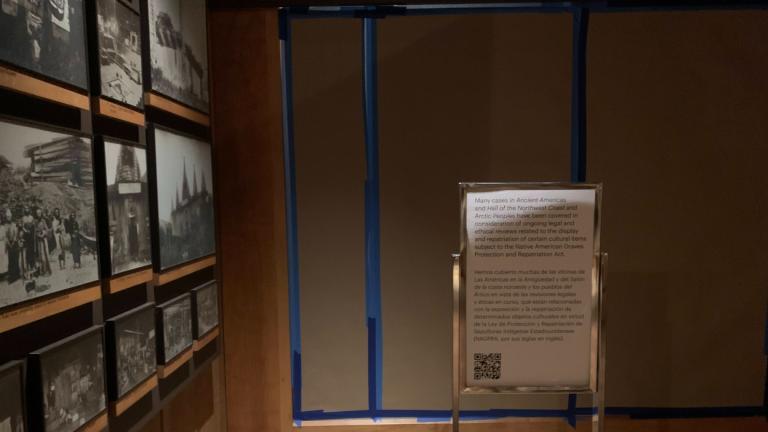

But along with showcasing Audubon’s masterwork, which took more than a decade to produce, the Field is also shining a light on the less savory aspects of the naturalist’s life. Aspects that, under a contemporary lens, have muddied the once-revered Audubon’s legacy.

As the exhibit’s introductory interpretive panel plainly states: “(Audubon) bought and sold enslaved people, plagiarized and exploited natural resources.”

Text panels accompanying the Field’s exhibit don’t shy away from John J. Audubon’s flaws. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Text panels accompanying the Field’s exhibit don’t shy away from John J. Audubon’s flaws. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The question of “What to do about Audubon?” has vexed scholars and birders alike in recent years, Stotz among them.

“I grew up being in Audubon societies from the time I was 8 or 10; I’ve been on boards of Audubon societies,” Stotz said. “But it’s only recently that I’ve come to really understand the historical flaws.”

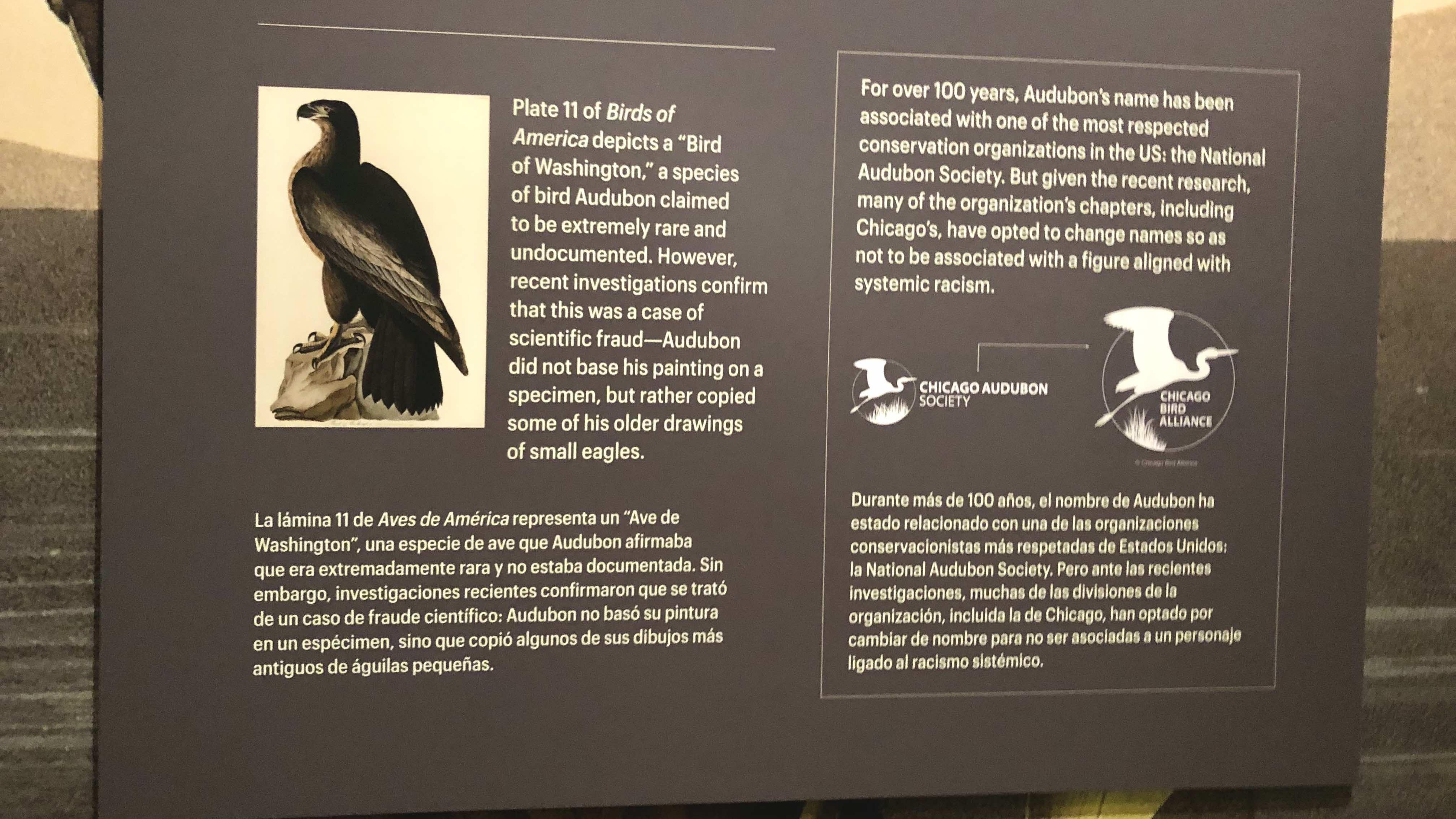

Organizations including the Chicago Audubon Society have scrubbed “Audubon” from their name — a point referenced in the exhibit — while the National Audubon Society has opted to retain the affiliation. Illinois Audubon Society, where Stotz is a board member, is still debating its stance. Stotz said he’s personally leaning toward losing the association with Audubon.

Audubon is also part of the broader conversation surrounding bird names. In late 2023, the American Ornithological Society announced it would begin the process of renaming all eponymous birds — birds named after people — whether the person involved is considered problematic or not.

“I would say Audubon’s birds are probably early on the chopping block because he has significant skeletons,” said Stotz.

These include obvious candidates like Audubon’s warbler (Setophaga auduboni) and Audubon’s oriole (Icterus graduacauda), Stotz said. Audubon is also credited with naming birds, as well, some of them after peers, such as Henslow’s sparrow (Centronyx henslowii), but others not, such as the western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta). Is everything touched by Audubon tainted?

“There’s a lot of value in keeping a name long-term because it means when you look at something that was written 100 years ago, it was western meadowlark, and it’s still western meadowlark,” Stotz said. “The question is, when does the name outweigh that? And we don’t fully know the answer to that. We’re sort of experimenting on how that plays out.”

Choosing a replacement name is fraught with its own landmines, as Stotz discovered when he served as a member of the committee charged with renaming the McCown’s longspur. McCown was an army officer involved in collecting specimens during expeditions into the western U.S., and later commanded confederate troops during the U.S. Civil War.

“That was the bird that sort of started us down this path,” Stotz said. “(McCown) was the one that we first went into this question about where do you fall when people have these negatives.”

The committee’s final choice for the bird was the anatomically correct but less-than-poetic thick-billed longspur. “And everybody hated it,” he said.

“Part of that relates to another issue, which is that birds tend to be named for the plumage of the males [e.g., scarlet tanager or black-throated green warbler],” he said. “And we decided we probably didn’t want to go from a confederate general to something named for the plumage of the male.”

The exhibit features floor-to-ceiling images drawn from “Birds of America.” (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The exhibit features floor-to-ceiling images drawn from “Birds of America.” (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Stotz is clear on the point that there are people who don’t deserve to have birds named after them. But where does that leave “Birds of America”?

An argument could be made that the volume should remain stashed away in an archive, but that would be a mistake on a couple of different levels, Stotz said.

There is, for one, the artistic merit of the drawings. To this day, many birders prefer field guides with illustrations rather than photos and will likely have thumbed through mass market versions of Audubon’s work.

“It’s kind of counterintuitive that you can be more realistic sometimes with paintings than the photo,” Stotz said.

“I don’t think you can appreciate how spectacular these things look in real life the way they were painted, when you’re used to having seen these things (copies) that are kind of dull and washed out,” he said. “The fact that you can even display it is pretty impressive.”

Amazingly, given his long tenure at the Field, Stotz has never leafed through the museum’s set of Audubon illustrations, which is now 190 years old.

“I don’t think many people will come back every month to see what the new (painting) is, but since I’m in the museum, I probably will,” he said.

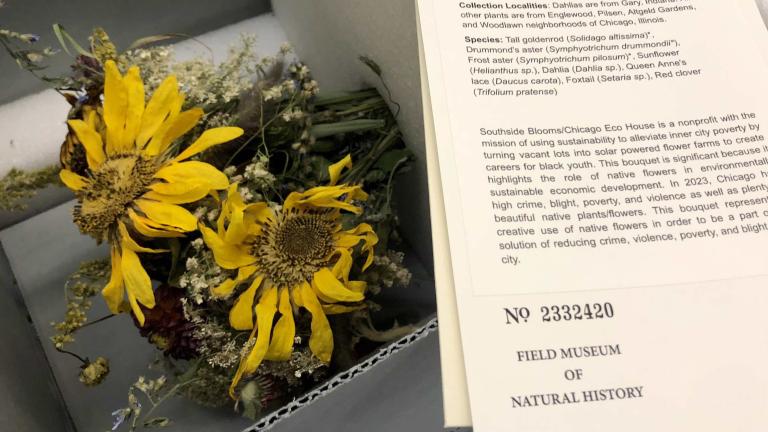

The hand-painted engravings in “Birds of America” were a leap forward in the science of ornithology. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The hand-painted engravings in “Birds of America” were a leap forward in the science of ornithology. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

From a scholarly perspective, “Birds of America” represents a huge leap forward in the field of ornithology.

“Birds of America” set the standard for knowledge of birds at the time, with detailed illustrations that were, to many, their first introduction to a given species. And by painting the birds in their natural habitats, Audubon also is responsible for some of the first high-quality images of native plants.

“I think if we put these things away and sort of just drop Audubon out of all the discussions, we will lose historical perspective,” Stotz said. “He was part of that piecing together of natural history, the natural world, when the U.S. was being created and was taking over the entire continent. I think you lose something if you don’t acknowledge that and think about it.”

What to do about Audubon?

The Field is encouraging visitors to understand why the question is being asked.

“He was a spectacular naturalist and bird painter, but he has some serious issues,” Stotz said. “I think we can acknowledge the great work he did while still recognizing and coming to terms with the fact that he had some horrible views and did some not nice things.”

The Field Museum’s copy of “Birds of America” is one of only 120 complete sets known to exist. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum’s copy of “Birds of America” is one of only 120 complete sets known to exist. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]