What can a mutant fruit fly can tell us about sleep? Why might forests in Alaska be contributing to climate change? And is Jupiter's Great Red Spot shrinking?

Neil Shubin, University of Chicago paleontologist and explainer of all things scientific, is back to discuss these stories and more.

Turning back the biological clock

After studying the biological clock of a mutant fruit fly, Northwestern University professor and chair of neurobiology Dr. Ravi Allada observed the clock’s mechanism to operate like a light switch between sodium and potassium currents, with the balance of the two currents controlling the fly’s circadian rhythms.

After studying the biological clock of a mutant fruit fly, Northwestern University professor and chair of neurobiology Dr. Ravi Allada observed the clock’s mechanism to operate like a light switch between sodium and potassium currents, with the balance of the two currents controlling the fly’s circadian rhythms.

According to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, “Circadian rhythms are physical, mental and behavioral changes that follow a roughly 24-hour cycle, responding primarily to light and darkness in an organism's environment. They are found in most living things, including animals, plants and many tiny microbes.”

Allada and his research team found the same sleep-wake switch that was discovered in the fly in mice as well. The switch, which is known as a “bicycle” mechanism, includes two pedals—sodium and potassium currents—that go up and down throughout a 24-hour day as they convey important time information to circadian neurons. In the case of a mouse: When the neurons fire more, the animal awakens; when the potassium current is high, the neurons fire less and cause the animal to go to sleep.

Does this mean that the sleep-wake switch exists in humans and does it have something to do with controlling our sleep-wake cycle? Is it possible for humans to reset their internal clocks? Allada seems to believe so, and the research could lead to new medications that address issues with clock-induced sleep-wake patterns in humans.

Alaska forest fires create carbon unbalance

A new study of forest fires in Alaska’s Yukon Flats reveals that, due to the increased activity of forest fires in the area, the location has become a net contributor of releasing carbon into the atmosphere.

A new study of forest fires in Alaska’s Yukon Flats reveals that, due to the increased activity of forest fires in the area, the location has become a net contributor of releasing carbon into the atmosphere.

Despite scientific assumptions that forest fire activity and the carbon cycle has remained relatively the same for thousands of years in the boreal forest region, the study shows that forest fire frequency in the area is greater today than at any other time in the past 10,000 years. The area contains more than 30 percent of the planet’s terrestrial carbon and, with too much of the forest going up in smoke, the fire increase has created major losses of carbon to the ecosystem and is creating an unbalance in the cycle of carbon capture and release.

Scientists fear that, with the climate of the Alaskan area warming up dramatically, forest fires are increasing which, in turn, will release even more carbon into the atmosphere and continue to enhance warming.

Jupiter’s diminishing Great Red Spot

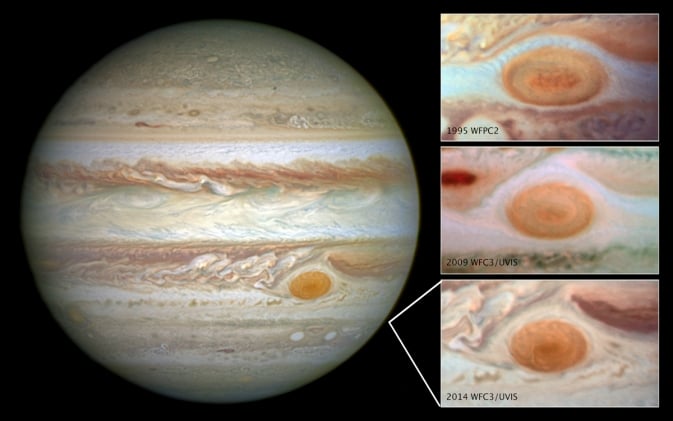

Images of Jupiter's Great Red Spot from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope taken over a span of 20 years show that the Great Red Spot is diminishing (Courtesy of Science@NASA)

Since the 1930s, astronomers have been observing the downsizing of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot—described by NASA as “a swirling anti-cyclonic storm larger than Earth.” According to recent photographs taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the Great Red Spot—once measured at 25,500 miles across its long axis—now measures at 10,250 miles across the solar system’s largest planet and has been shifting its shape from an oval to a circle as the spot has shrunk by 580 miles per year since 2012.

Images of Jupiter's Great Red Spot from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope taken over a span of 20 years show that the Great Red Spot is diminishing (Courtesy of Science@NASA)

Since the 1930s, astronomers have been observing the downsizing of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot—described by NASA as “a swirling anti-cyclonic storm larger than Earth.” According to recent photographs taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the Great Red Spot—once measured at 25,500 miles across its long axis—now measures at 10,250 miles across the solar system’s largest planet and has been shifting its shape from an oval to a circle as the spot has shrunk by 580 miles per year since 2012.

How can the shrinkage be explained? NASA’s Juno spacecraft is travelling toward Jupiter to help search for clues and is expected to reach the giant gas planet in July 2016.

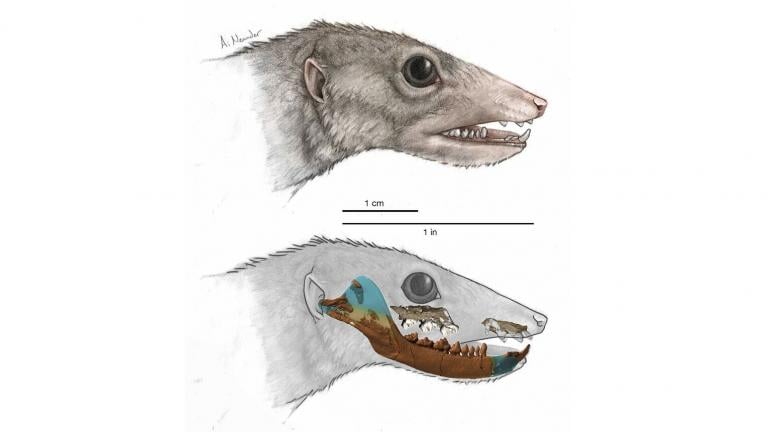

A 125 million-year-old well-preserved fossil of a rat-like mammal named "Spinolestes xenarthrosus" has been discovered in the Las Hoyas Quarry in Spain. The findings are now the earliest recorded evidence of preserved mammalian hair structures, skin and inner organs by more than 60 million years.

The fossil is believed to be from an extinct line of early mammals known as triconodonts that lived during the Cretaceous period. With its modern mammalian hair and skin structures, "Spinolestes" offers scientists new proof that fundamental mammalian characteristics were already established during the time when the dinosaurs walked the Earth.

In case you missed it: Last week, Rabiah Mayas of the Museum of Science and Industry joined us to talk about a new baseball statistic that could help the Chicago Cubs and a new tool that could revolutionize cancer treatment, among other stories.

In case you missed it: Last week, Rabiah Mayas of the Museum of Science and Industry joined us to talk about a new baseball statistic that could help the Chicago Cubs and a new tool that could revolutionize cancer treatment, among other stories.